Wildland Fires Emit Far More Air Pollution Than Scientists Previously Estimated

Wildland fires have long been known to pollute the air, but new research suggests their impact is significantly larger than scientists once believed. A recent global study reveals that wildfires and prescribed burns emit far greater amounts of harmful airborne organic compounds than earlier estimates captured. This discovery reshapes how researchers understand fire-related air pollution and highlights new challenges for public health, air-quality modeling, and climate policy.

Wildland fires include both uncontrolled wildfires and controlled burns used for land management. As vegetation burns, it releases a complex mix of gases and particles into the atmosphere. Until now, many of these emissions were systematically underestimated, particularly those compounds that play a major role in forming fine particulate pollution.

A 21% Jump in Estimated Emissions

The study, published in Environmental Science & Technology, finds that global wildland fire emissions of organic compounds are about 21% higher than previous inventories suggested. On average, fires released approximately 143 million tons of airborne organic compounds per year over the study period.

This increase is not a minor adjustment. It represents a major correction to how scientists quantify the pollution produced by fires worldwide. The researchers describe their work as a full-volatility emissions inventory, meaning it includes a broader range of organic compounds than earlier models.

Why Previous Estimates Fell Short

Most earlier assessments focused primarily on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and primary particles emitted directly from fires. VOCs are gases that easily evaporate at normal temperatures and are known contributors to air pollution.

However, the new study shows that fires also emit large quantities of intermediate-volatility organic compounds (IVOCs) and semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs). These compounds are harder to measure because they exist in large numbers and can behave as both gases and particles depending on temperature and atmospheric conditions.

Once released into the air, IVOCs and SVOCs are especially effective at forming fine particulate matter, often referred to as PM2.5. These fine particles are small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and are associated with respiratory and cardiovascular health problems. Because IVOCs and SVOCs were largely overlooked in past inventories, the pollution burden from wildland fires was consistently underestimated.

How the Researchers Built a Better Inventory

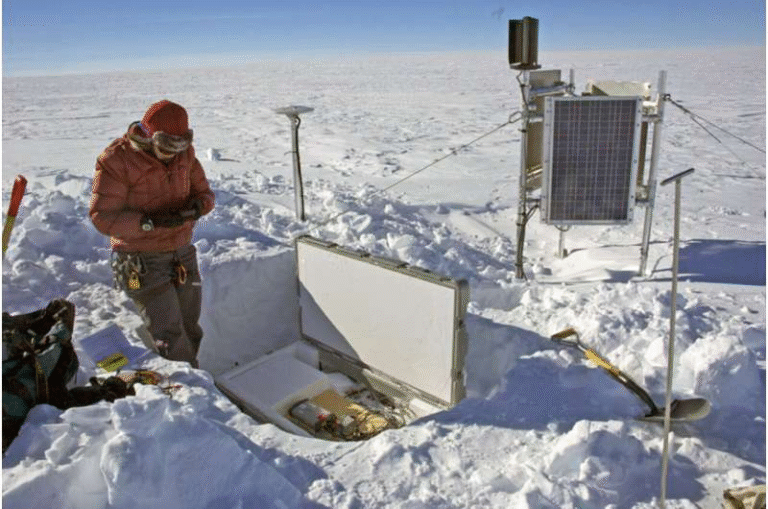

To address this gap, the research team analyzed global wildland fire activity from 1997 to 2023. They began by accessing a comprehensive database of burned land areas, covering forests, grasslands, and peatlands worldwide.

Next, they gathered detailed data on the organic compounds released when each type of vegetation burns. Where field measurements were available, those were used directly. For vegetation types lacking real-world measurements, the researchers relied on laboratory combustion experiments to estimate emissions of VOCs, IVOCs, SVOCs, and even extremely low-volatility organic compounds.

By combining burned-area data with these emission factors, the team calculated annual global emissions over more than two decades. The result is one of the most detailed and inclusive estimates of wildland fire pollution to date.

Fires vs. Human-Caused Emissions

The researchers also compared emissions from wildland fires with those produced by human activities, such as transportation, industry, and residential energy use. Overall, human activities still release more airborne organic compounds than fires.

However, when it comes specifically to IVOCs and SVOCs, the picture changes. The study finds that wildland fires and human activities emit roughly equivalent amounts of these particularly pollution-forming compounds. This finding underscores how important fires are as a source of air pollution, especially during active fire seasons.

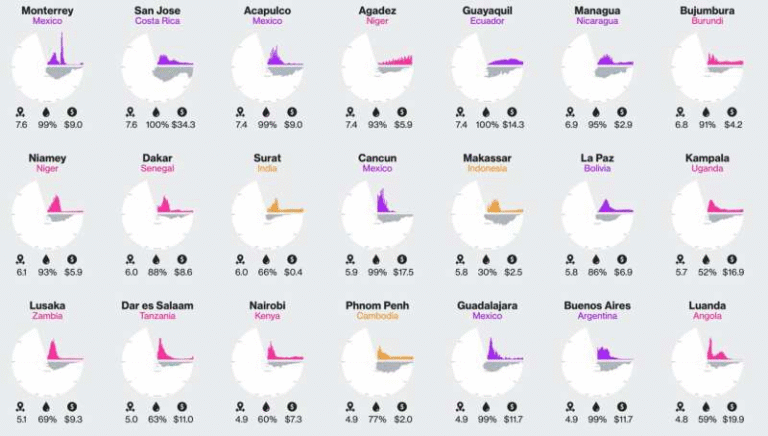

Global Hotspots with Complex Air-Quality Challenges

The analysis identified several regions where emissions from wildland fires and human activities overlap, creating especially difficult air-quality conditions. These emission hotspots include:

- Equatorial Asia

- Northern Hemisphere Africa

- Southeast Asia

In these regions, pollution does not come from a single source. Instead, smoke from fires mixes with emissions from cities, agriculture, and industry. According to the researchers, this overlap means that one-size-fits-all solutions will not work. Reducing air pollution in these areas requires coordinated strategies that address both fire management and human-caused emissions.

What This Means for Health and Climate

Fine particulate matter formed from IVOCs and SVOCs is a major health concern. Exposure to PM2.5 has been linked to asthma, chronic lung disease, heart attacks, and premature death. If wildland fires are producing more of these pollution-forming compounds than previously believed, then their health impacts may also be greater.

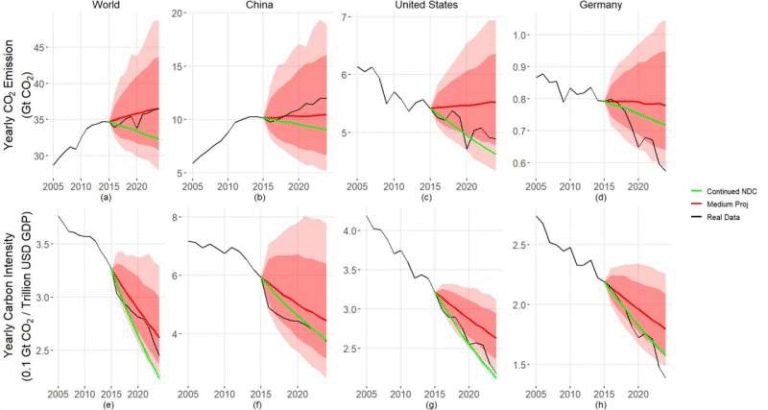

From a climate perspective, organic aerosols influence how sunlight is absorbed or reflected in the atmosphere and can affect cloud formation. Underestimating these emissions means climate models may not fully capture the role of fires in regional and global climate systems.

The researchers emphasize that their updated inventory provides a stronger foundation for air-quality modeling, health-risk assessments, and climate-related policy analysis.

Why Wildland Fire Pollution Is Likely to Grow

Wildland fire activity is expected to increase in many parts of the world due to climate change. Rising temperatures, prolonged droughts, and changing land-use patterns are creating conditions that allow fires to burn more frequently and more intensely.

As fire seasons lengthen, the contribution of wildland fires to air pollution could become even more significant. Improved emission inventories like this one are essential for preparing public health systems and guiding policies aimed at reducing exposure during smoke events.

Understanding IVOCs and SVOCs a Bit More

IVOCs and SVOCs sit between gases and particles in terms of volatility. When released from fires, they can travel long distances as gases before transforming into particles downwind. This means people far from the original fire can still experience smoke-related air pollution, even if local fires are not burning.

Because these compounds were underrepresented in older datasets, air-quality forecasts may have underestimated how much smoke-related pollution forms after fires. Including them improves predictions of where and when air quality will deteriorate.

A Step Toward More Accurate Fire Science

This study represents a significant step forward in understanding wildland fire emissions. By accounting for the full range of organic compounds, researchers now have a clearer picture of how much pollution fires release and how that pollution behaves in the atmosphere.

As wildfires continue to shape air quality across the globe, having accurate, up-to-date emissions data will be critical. This research does not just revise a number upward; it reshapes how scientists, policymakers, and the public think about the true environmental cost of burning landscapes.

Research paper: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5c10217