K-12 Teachers Explore Three-Dimensional Math Through a New Multiplayer Virtual Reality Environment

A new study from the University of Maine offers an interesting look at how K-12 teachers engage with mathematical ideas when those ideas are placed inside an immersive virtual world. The project centers on TriO, a three-player virtual reality environment developed by the university’s Immersive Mathematics in Rendered Environments (IMRE) Lab. The goal is simple but ambitious: give teachers and students a way to explore geometry, coordinate systems, and the structure of three-dimensional space by actually moving through it, instead of sketching it on paper.

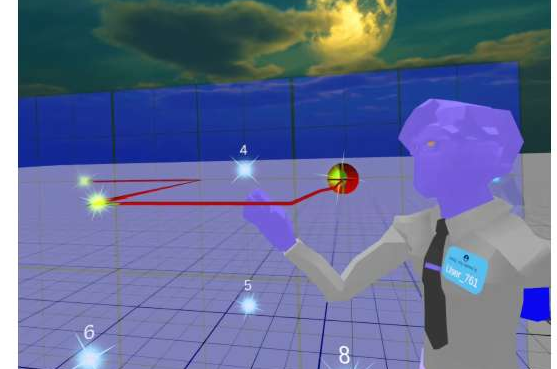

At its core, TriO is meant to shift how people think about math learning. Instead of a worksheet or a textbook demonstrating the x, y, and z axes, TriO turns these axes into interactive controls that three players manipulate together. Each user is responsible for one axis: a red handle for x, green for y, and blue for z. By pushing or pulling these handles, players move a shared object—a small disk-like widget—around a 3-D virtual environment. The movement is continuous, collaborative, and directly tied to the spatial mathematics that teachers normally teach in two dimensions.

The study, published in Digital Experiences in Mathematics Education, focused on how six high school teachers used this environment during a three-day workshop at the IMRE Lab. Researchers Justin Dimmel and Matthew Patterson gave teachers full freedom to decide how they wanted to use TriO, how they wanted to move through the space, and how they organized themselves as a team. The idea was to treat the teachers not as passive participants but as co-designers, helping shape the future of the environment with their feedback and exploration.

One of the key observations from the study came from watching the teachers navigate the widget together. Because each person controls only one axis, success requires communication, timing, and coordination. Teachers described moments where they found themselves naturally discussing which handle to move, when to move it, and how far. This collaborative requirement is built into the system intentionally—TriO is designed to encourage the kind of interaction that helps students develop both spatial awareness and teamwork.

In one case, a group of teachers worked together to guide the widget to every vertex of a cube along a diagonal path. In typical classroom settings, a task like this might involve flattening a 3-D shape into a 2-D diagram, which can distort the true relationships between the cube’s points. TriO avoids this representational problem entirely; the cube exists in its full three dimensions, and the participants move through it naturally. It’s a way of helping users feel the structure of space rather than simply drawing it.

TriO’s development builds on an earlier two-player environment called Ortho, created by Dor Abrahamson at the University of California, Berkeley. Abrahamson suggested expanding Ortho into a three-person version, which became the foundation for TriO. Patterson coded the new system using Unity, a widely used game engine that supports both 2-D and 3-D software. TriO can run on any standard virtual reality headset, which makes it easier for teachers or schools to access without needing specialized hardware.

The IMRE Lab, led by Dimmel, has been exploring how embodied experiences—that is, experiences involving physical movement—can support mathematical thinking. Their work often looks at how virtual reality and augmented reality can make abstract concepts more intuitive. For example, earlier research from the lab examined how immersive tools can help people understand geometric surfaces, lines, and spatial relationships that are otherwise difficult to visualize or draw accurately. TriO continues that pattern by placing users directly inside a coordinate system rather than asking them to imagine one.

The study provided what the research team calls a proof-of-concept. The focus groups revealed that teachers were enthusiastic about the potential of virtual environments like TriO, especially for helping students who struggle with abstract reasoning. Because TriO converts mathematical structures into physical actions, it allows learners to develop an instinctive sense of how movement along one axis affects position in space. This can be especially useful for students who benefit from hands-on or visual learning styles.

Another important aspect of the study is that teachers were not given a fixed curriculum. Instead, they were encouraged to explore and reflect on how they might use the environment in their own classrooms. This approach acknowledges that teachers bring their own goals, constraints, and teaching styles. The researchers argue that VR tools should be adaptable rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all lesson plan.

Beyond the study itself, TriO represents a growing interest in how multiplayer VR can support education. Many VR applications place a single user inside a virtual space, but shared environments offer possibilities that individual systems can’t. When users collaborate in VR, they must negotiate, plan, and adjust their actions together—skills that mirror the kinds of group work teachers already value. TriO’s design shows that VR doesn’t need to isolate users; it can actually enhance social learning.

From a mathematical perspective, TriO’s focus on R³ (three-dimensional space) taps into a foundational idea in geometry and physics. The Cartesian coordinate system, which includes the familiar x, y, and z axes, is used everywhere—from computer graphics to engineering to GPS mapping. Students usually work with these concepts in two dimensions first, which can create gaps when they later encounter 3-D problems. A virtual environment that allows them to manipulate object position directly could serve as a bridge between the introductory material and more advanced applications.

Virtual reality also solves a long-standing challenge in math education: representing three-dimensional structures on flat surfaces. When students look at 3-D drawings on paper, they have to mentally reconstruct the shape in their minds, which is a skill that develops unevenly. VR bypasses the need for this reconstruction. Instead of imagining how a cube looks from another angle, a student can simply walk around it.

The IMRE Lab’s work suggests that virtual environments like TriO can create experiential learning opportunities that traditional tools cannot. They allow learners to test ideas, refine their intuition, and develop spatial reasoning in a more natural and interactive way. While the study involved only six teachers, the findings help imagine how larger groups of educators and students could one day use VR to explore mathematical concepts that often feel out of reach.

As VR technology becomes more accessible and more schools explore digital tools for learning, systems like TriO may become increasingly common. For now, this study shows what’s possible when educators step inside a virtual space designed specifically for mathematical thinking and collaborate to move through it. The combination of movement, teamwork, and three-dimensional reasoning makes TriO an intriguing platform not only for future research but also for practical classroom use.

Research Paper:

TriO: A Multiplayer, Immersive, Virtual Environment for Exploring R³

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40751-025-00182-z