A Common Genetic Variant May Explain Why Some Lung Transplant Patients Face Higher Rejection Risk

Lung transplantation can be life-saving for people with end-stage lung disease, but long-term success remains a major challenge. Among all solid organ transplants, lung transplants still have the poorest long-term survival rates, and the biggest reason is chronic rejection. A new study from UCLA Health sheds light on why some patients are more vulnerable than others, pointing to a specific genetic variant that appears to raise the risk of chronic lung rejection in a significant portion of recipients.

Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction and Why It Matters

The main threat to long-term lung transplant survival is a condition called chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD). CLAD refers to a gradual and irreversible decline in lung function caused by immune-mediated injury to the transplanted organ. Over time, this damage makes breathing progressively more difficult and is the leading cause of death years after lung transplantation.

Despite advances in surgery and post-transplant care, CLAD remains difficult to prevent or treat. Standard anti-rejection medications, while effective at controlling early immune responses, often fail to stop the slow, chronic immune processes that drive long-term damage. This has left researchers searching for deeper biological explanations behind why CLAD develops in some patients but not others.

The Role of a Key Genetic Variant

In the new study, researchers focused on a gene called C3, which plays a central role in the complement system. The complement system is a critical part of the immune system, helping the body recognize, mark, and clear infections and damaged cells. It also helps clean up debris in tissues, including transplanted organs.

The researchers analyzed two independent groups of lung transplant recipients and found that about one-third of patients carried a specific variant in the C3 gene. This variant impairs the body’s ability to properly regulate complement activity. In both patient cohorts, individuals with this variant were significantly more likely to develop CLAD than those without it.

This finding is important because it suggests that genetic makeup alone may predispose certain patients to worse long-term outcomes, even when they receive similar medical care and immunosuppressive therapy.

Why Complement Regulation Is So Important

Under normal conditions, the complement system is tightly controlled. It activates quickly when needed, then shuts down to avoid damaging healthy tissue. The C3 gene variant identified in the study disrupts this balance, leading to excessive or prolonged complement activation.

In the context of a transplanted lung, this overactive complement response can be harmful. The lung is constantly exposed to air, microbes, and environmental particles, making it especially vulnerable to immune-mediated injury. When complement regulation is impaired, immune activity in the transplanted lung may escalate rather than resolve.

The Link Between Complement and Antibodies

One of the most striking findings from the study was how this genetic variant interacts with donor-specific antibodies. These antibodies are produced by the recipient’s immune system and specifically target proteins from the donor lung.

Patients who carried the C3 variant and also developed donor-specific antibodies had an even higher risk of chronic rejection. This combination appeared to accelerate the progression of CLAD and worsen long-term outcomes.

To understand why this happens, the research team turned to experimental models.

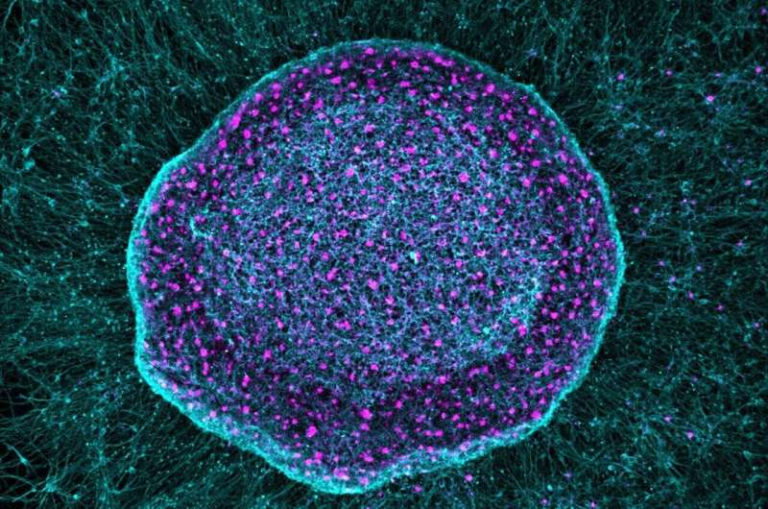

Insights From a Mouse Lung Transplant Model

The researchers used a mouse lung transplant model designed to mimic impaired complement regulation similar to what is seen in humans with the C3 variant. These experiments revealed a critical mechanism that current therapies do not adequately address.

Impaired complement regulation activated certain B cells, a type of immune cell responsible for producing antibodies. Once activated, these B cells generated antibodies that attacked the transplanted lung tissue. This antibody-driven process led to chronic inflammation and structural damage in the lung, closely resembling CLAD seen in human patients.

Importantly, standard anti-rejection drugs are primarily designed to suppress T cell–mediated immune responses. The study showed that these medications do not fully control complement-driven B cell activation, helping explain why chronic rejection can progress even when patients are carefully managed.

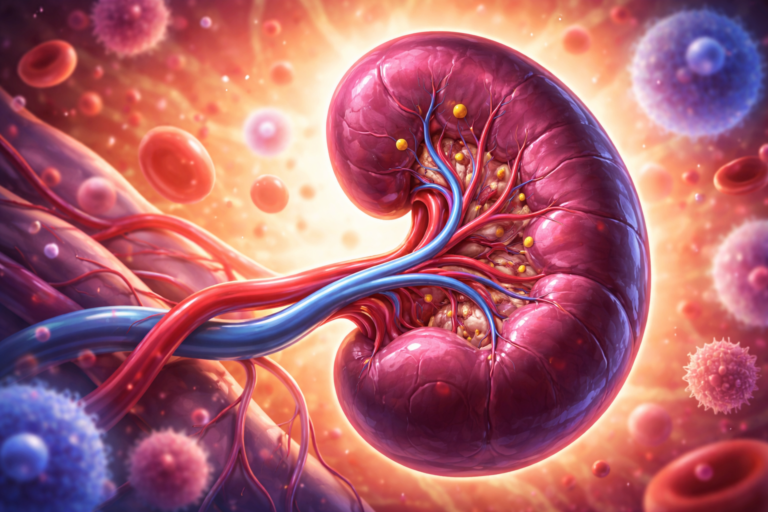

Why Lung Transplants Are Especially Vulnerable

Compared with other transplanted organs, lungs face unique challenges. They are constantly exposed to the outside environment and must maintain a delicate balance between immune defense and tolerance. This makes them particularly sensitive to subtle changes in immune regulation.

The study highlights how innate immune mechanisms, such as the complement system, can shape long-term outcomes just as much as adaptive immune responses. It also helps explain why lung transplantation has lagged behind kidney, liver, and heart transplants in terms of long-term survival.

What This Means for Patients and Clinicians

One of the most promising implications of this research is the potential for personalized transplant care. If genetic testing identifies patients who carry the C3 variant, clinicians may be able to monitor them more closely for early signs of antibody development and chronic rejection.

In the future, genetic information could help guide treatment decisions, risk stratification, and follow-up strategies. Rather than treating all lung transplant recipients the same way, care could be tailored based on underlying biological risk factors.

New Directions for Treatment

The findings also point toward new therapeutic targets. Because the complement system plays a central role in this process, complement-modulating therapies may offer a new way to protect transplanted lungs. Drugs that inhibit specific complement pathways already exist and are used in other immune-mediated diseases, though they are not yet standard treatment for CLAD.

While more research is needed before these approaches can be applied clinically, the study opens the door to treatment strategies that go beyond broad immunosuppression and focus on the specific pathways driving chronic rejection.

Expanding Our Understanding of Transplant Immunology

Beyond lung transplantation, this research adds to a growing understanding of how genetics and innate immunity influence transplant outcomes. It reinforces the idea that long-term graft survival is not determined by a single factor, but by complex interactions between genes, immune pathways, and environmental exposures.

By identifying a concrete biological mechanism behind chronic rejection, the study moves the field closer to interventions that could finally improve long-term survival for lung transplant recipients.

Looking Ahead

Chronic lung allograft dysfunction currently has no cure, and treatment options remain limited. However, discoveries like this provide a clearer roadmap for future research and clinical innovation. Understanding who is at risk, why that risk exists, and how it develops is the first step toward changing outcomes.

As research continues, this genetic insight may help transform lung transplantation from a life-saving procedure with uncertain longevity into one with more predictable and durable success.

Research reference:

https://www.jci.org/articles/view/188891