A High-Protein Diet Can Defeat Cholera Infection, According to New Research

A new study from the University of California, Riverside (UCR) suggests that something as simple and accessible as diet could play a major role in fighting cholera, a deadly bacterial infection that continues to threaten millions of people worldwide. The research shows that diets high in specific proteins, particularly casein and wheat gluten, can dramatically reduce the ability of cholera bacteria to infect the gut.

Cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae and is best known for triggering severe diarrhea and dehydration. Without timely treatment, the disease can be fatal. While clean water, sanitation, and rehydration therapy remain the cornerstones of cholera prevention and treatment, this study adds an intriguing new layer: what we eat may influence how well cholera can take hold inside the body.

What the Study Found

The research team set out to understand whether diet could influence not just beneficial gut microbes, but also infectious pathogens like Vibrio cholerae. Scientists already know that food strongly shapes the gut microbiome, the complex community of bacteria living inside us. What was less clear was whether diet could also affect the behavior of harmful invaders.

To test this, the researchers infected mice with cholera bacteria and fed them different diets. These included diets high in protein, high in simple carbohydrates, and high in fat. The results were striking.

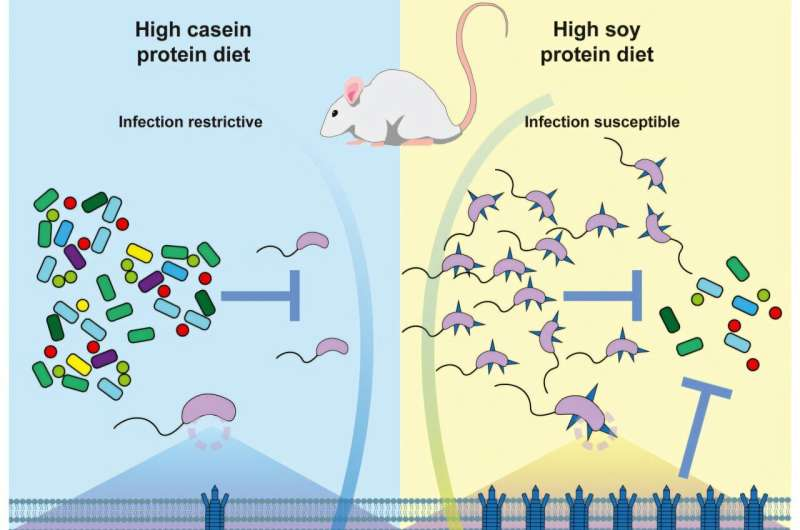

Mice fed high-fat diets showed little resistance to infection. Diets rich in carbohydrates offered only limited protection. But diets high in casein, the main protein found in milk and cheese, and wheat gluten, the primary protein in wheat, produced a dramatic effect. In some cases, the amount of cholera bacteria in the gut dropped by up to 100-fold compared to mice on a balanced diet.

This level of difference surprised even the researchers. The effect was not subtle—it was large enough to suggest that diet alone could significantly change the outcome of infection.

Not All Proteins Are the Same

One of the most important takeaways from the study is that protein type matters. Simply eating more protein is not enough. Among the proteins tested, casein and wheat gluten clearly stood out as the most effective at limiting cholera colonization.

Other protein sources did not show the same protective effect. This finding suggests that specific components or breakdown products of these proteins interact with the bacteria or the gut environment in unique ways. Understanding exactly why these proteins are so effective is now an active area of research.

How Protein Weakens Cholera Bacteria

Digging deeper, the scientists discovered that these proteins interfere with a critical weapon used by cholera bacteria. Vibrio cholerae relies on a microscopic, syringe-like structure called the Type VI Secretion System (T6SS). This structure allows the bacteria to inject toxins into neighboring cells, kill competing microbes, and carve out space for itself in the gut.

When mice consumed diets rich in casein or wheat gluten, the activity of the T6SS was significantly suppressed. With this system muted, cholera bacteria struggled to kill other gut microbes and were far less successful at establishing infection.

In simple terms, the high-protein diet didn’t kill cholera directly. Instead, it disarmed the bacteria, making it weaker and less competitive inside the gut.

Why This Matters for Global Health

Cholera remains a serious public health problem, particularly in parts of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where access to clean water and sanitation is limited. Current treatment focuses on rehydration therapy, which saves lives but does not stop the bacteria from producing toxins. Antibiotics can shorten the duration of illness, but they come with risks, including the potential development of antibiotic resistance.

Dietary strategies offer a different kind of tool. Foods rich in casein and wheat gluten are already widely consumed and considered safe from a regulatory standpoint. Unlike antibiotics, dietary interventions are unlikely to drive resistance or cause sudden changes in bacterial behavior.

Because of this, dietary approaches could serve as a low-cost, low-risk complement to existing cholera control strategies, especially in vulnerable populations.

From Mice to Humans

It is important to note that this study was conducted in mice, not humans. While mouse models are widely used and provide valuable insights, human biology is more complex. That said, the researchers expect similar effects in people and are interested in testing how high-protein diets influence human microbiomes.

If future studies confirm these findings in humans, dietary guidance could become part of broader efforts to reduce the severity or likelihood of cholera infection. This could be especially impactful in regions where medical resources are limited but dietary changes are feasible.

Diet, the Microbiome, and Infectious Disease

This research fits into a growing body of evidence showing that diet shapes not only our general health, but also our susceptibility to infectious diseases. The gut microbiome acts as a frontline defense, competing with pathogens for space and nutrients. When diet strengthens this microbial community, harmful bacteria may find it harder to gain a foothold.

The study also hints that similar dietary effects might apply to other infectious bacteria, not just cholera. If specific foods can weaken bacterial virulence systems, diet could become a powerful, underused tool in disease prevention.

Understanding Cholera Beyond the Headlines

Cholera has been studied for over a century, yet it continues to surprise scientists. The disease spreads primarily through contaminated water and food, and outbreaks often follow natural disasters or infrastructure breakdowns. While vaccines exist, they are not always widely available or long-lasting in their protection.

This new research does not suggest replacing vaccines, clean water initiatives, or medical treatment. Instead, it highlights how nutrition and microbiology intersect in ways that could strengthen public health efforts.

Looking Ahead

The findings from UC Riverside open the door to new questions. Which components of casein and wheat gluten are responsible for suppressing cholera’s virulence? Can similar effects be achieved with plant-based alternatives? How do these dietary changes interact with diverse human diets and microbiomes around the world?

As researchers continue exploring these questions, one thing is clear: what we eat may play a bigger role in fighting infectious diseases than previously thought.

Research paper reference:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2025.11.004