A Key Brain Protein May Shape How We Learn to Link Cues With Rewards

Researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center have uncovered new details about how the brain learns to connect everyday cues with rewards—and why this process can sometimes go wrong. The study focuses on a protein called KCC2, showing that changes in its activity can strongly influence how reward-related learning happens in the brain. This discovery has important implications for understanding addiction, depression, schizophrenia, and other brain disorders where learning and motivation are disrupted.

At its core, reward learning helps us decide when to act and when to hold back. It allows us to respond positively to cues that lead to beneficial outcomes—like working hard for a promotion—while ignoring cues tied to harmful habits, such as smoking or drug use. The new research suggests that KCC2 plays a central role in maintaining this balance.

How the Brain Learns From Cues and Rewards

The brain constantly links stimuli (or cues) with outcomes. A sound, smell, or visual signal can become meaningful if it reliably predicts a reward. This process is deeply tied to the brain’s dopamine system, which is involved in reward, motivation, and reinforcement learning.

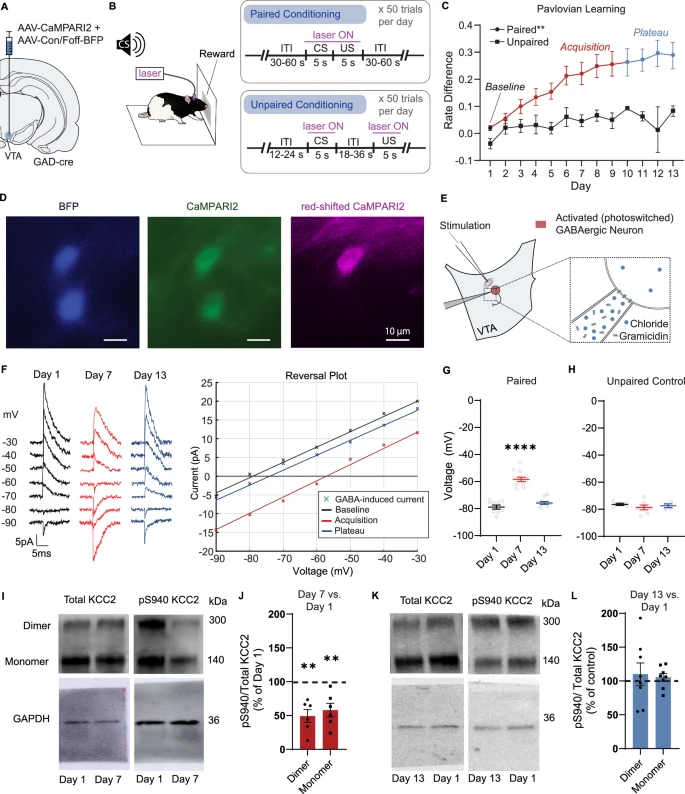

The Georgetown researchers found that the learning process itself can be altered depending on how active the KCC2 protein is. KCC2 is a potassium-chloride cotransporter that helps regulate chloride levels inside neurons, which in turn affects how inhibitory signals work in the brain.

When KCC2 levels are reduced, dopamine neurons become more excitable. This leads to increased dopamine firing, making it easier for the brain to form new reward associations. In contrast, when KCC2 activity is higher, dopamine neuron firing is more restrained, and learning those associations becomes less intense.

This inverse relationship between KCC2 activity and dopamine firing highlights how finely tuned the brain’s learning machinery really is.

Why Dopamine Neurons Matter So Much

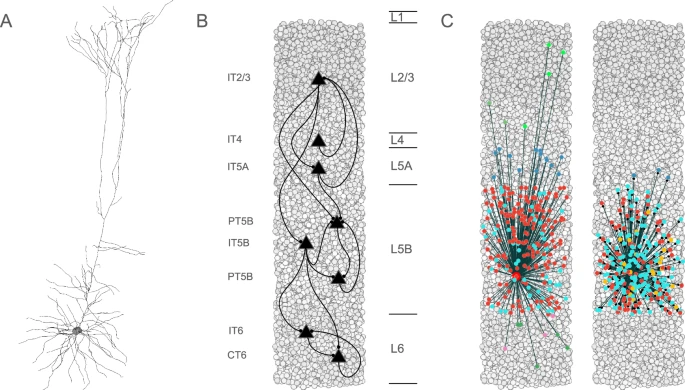

Dopamine neurons are specialized nerve cells that produce and release dopamine, a neurotransmitter crucial for reward, motivation, learning, and movement. Short bursts of dopamine activity act as signals that tell the brain something important has happened—especially when an outcome is better than expected.

In this study, the researchers discovered that dopamine neurons don’t just fire more or less depending on KCC2 levels. They can also fire in a coordinated, synchronized manner, and this synchronization can dramatically boost dopamine signaling.

These brief dopamine bursts appear to be key signals that help the brain assign value to shared learning experiences. In other words, synchronized activity makes learning more efficient and more powerful.

Experiments in Rats Reveal the Learning Mechanism

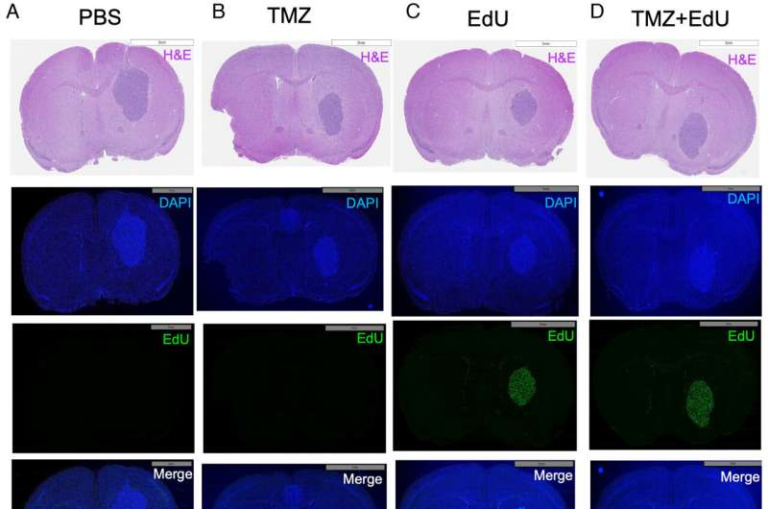

To explore this process in detail, the research team examined rodent brain tissue and conducted behavioral experiments using lab rats. The rats were trained in classic Pavlovian cue-reward tasks, where a neutral signal—such as a short sound—predicts the delivery of a sugar reward.

Over time, the rats learned to associate the cue with the reward. The researchers observed that altering KCC2 levels changed how quickly and strongly these associations formed.

Rats were chosen instead of mice for the behavioral experiments because rats tend to perform more reliably on longer and more complex tasks. Their consistent performance helped the researchers collect more stable and meaningful data, especially in experiments involving reward learning over time.

Addiction and the Problem of Unwanted Associations

One of the most striking implications of this research is its relevance to addiction. Drug abuse is known to alter normal brain chemistry, and previous work has shown that addictive substances can disrupt KCC2 function.

According to the researchers, changes in KCC2 caused by drugs may allow addictive substances to hijack the learning process. When KCC2 levels drop, dopamine neurons fire more easily, making it much simpler for powerful and unwanted associations to form.

This helps explain why certain cues—like drinking coffee in the morning—can trigger intense cravings for cigarettes in smokers, even after they try to quit. The brain has learned to strongly associate those cues with a reward, and that learning becomes hard to undo.

Preventing the formation of these associations, or restoring healthy learning mechanisms once they are disrupted, could be a major step forward in treating addiction and related disorders.

The Role of Inhibitory Neurons and Coordination

Beyond dopamine alone, the study highlights a new dimension of neuronal function. Neurons don’t just change how active they are—they also change how they coordinate with each other.

The researchers found that inhibitory neurons in the midbrain can act in a synchronized way. When they do, this coordination can unexpectedly increase dopamine neuron firing rather than suppress it. This coordinated activity allows information to be transmitted more efficiently across neural networks.

This finding challenges simpler views of inhibition in the brain and shows how complex and dynamic neural communication can be during learning.

How Drugs Like Diazepam Fit Into the Picture

The study also examined whether certain drugs that act on cellular receptors could influence these learning mechanisms. The researchers looked at benzodiazepines, a class of calming drugs that includes diazepam, commonly known as Valium.

Previous research had already shown that changes in KCC2 production can alter how diazepam produces its calming, inhibitory effects. In the current study, the team found that drugs like diazepam can aid neuronal coordination, further influencing dopamine signaling and learning.

This suggests that medications may have more complex effects on learning and reward systems than previously thought, depending on how they interact with proteins like KCC2.

A Wide Range of Experimental Approaches

To reach their conclusions, the research team combined many advanced techniques. These included electrophysiology to measure neuron firing, pharmacology to study drug effects, fiber photometry to track real-time neural activity, behavioral experiments, computational modeling, and molecular analyses.

This multi-layered approach allowed the researchers to connect changes at the molecular level with neuron activity, network coordination, and observable behavior.

Broader Implications for Brain Disorders

The researchers believe these discoveries extend far beyond basic learning research. By revealing new ways the brain regulates communication between neurons, the study opens doors to better understanding a wide range of brain disorders.

When neural communication goes wrong, learning and motivation can suffer. This is a hallmark of conditions such as addiction, depression, and schizophrenia. By identifying how proteins like KCC2 shape learning and dopamine signaling, scientists may be able to develop more targeted and effective treatments in the future.

Rather than focusing only on symptoms, this line of research points toward addressing the underlying communication problems within brain circuits.

Why KCC2 Is Gaining Attention in Neuroscience

KCC2 has traditionally been studied for its role in maintaining proper inhibitory signaling in the brain. This study adds another layer, showing that KCC2 is also deeply involved in learning and reward processing.

As research continues, KCC2 may emerge as a key target for therapies aimed at restoring healthy brain function—not just in addiction, but across a spectrum of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66838-x