A New Tabletop Blast Device Brings Traumatic Brain Injury Research Into the Lab With Unexpected Simplicity

Researchers at the University of Rhode Island have developed a low-cost, easy-to-use, and surprisingly accessible tabletop device that can generate realistic blast-like pressure waves, making it possible to study traumatic brain injury (TBI) on human brain organoids directly at the lab bench. This development could significantly expand how scientists investigate the roots of neurodegenerative diseases linked to TBI, such as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

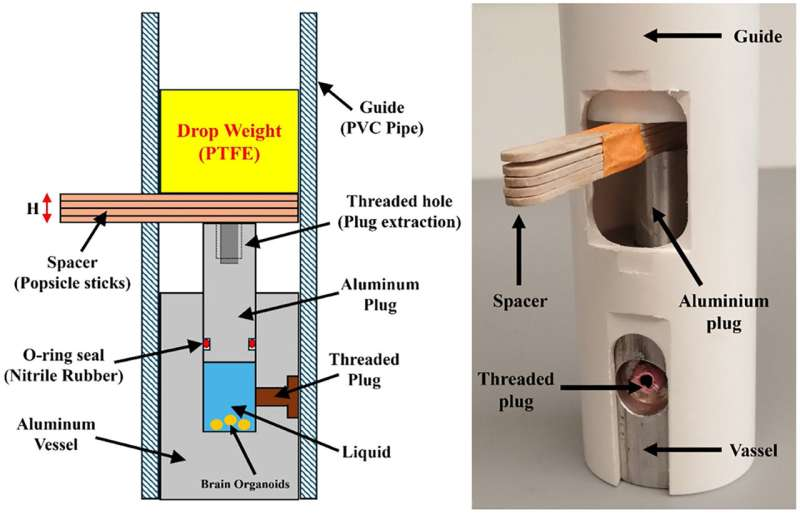

What makes this device so interesting is not just what it does, but how it came together—through a collaboration between cell biologists seeking better tools and engineering experts used to working on Navy-grade blast mitigation projects. The resulting invention is not a massive industrial-scale machine. Instead, it is a cleverly engineered, miniaturized 3-meter water-filled shock tube and benchtop simulator constructed from PVC pipe, aluminum components, and even popsicle sticks. Yet despite its humble appearance, it can deliver extreme pressure pulses—less than a millisecond long—that closely mimic those produced by real-world explosive blasts such as an IED detonation or a weapon firing.

Why This Device Was Needed

More than 65 million people worldwide experience some form of TBI each year. Among these injuries, blast-related TBIs are especially damaging and are strongly correlated with later neurodegeneration. In fact, a single moderate-to-severe TBI can increase a person’s risk of developing dementia fourfold.

Although animal models exist, researchers have struggled to replicate blast injuries using human-relevant systems. In recent years, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived brain organoids have emerged as one of the most promising tools because they mimic many aspects of human brain structure and function. But simulating blast injury on these organoids has been difficult. The equipment typically required is:

- expensive,

- highly specialized, and

- often not available in standard biology labs.

Claudia Fallini, an associate professor at URI’s College of the Environment and Life Sciences, had been searching for a practical way to model TBI without using animals and without needing million-dollar equipment. Existing methods in the scientific literature were either too complex or financially out of reach.

This gap—between what researchers wanted to study and the tools available—essentially sparked the project.

How the Collaboration Came Together

Fallini and postdoctoral fellow Riccardo Sirtori had the biological expertise but not a workable blast-simulation system. So they partnered with URI engineering researchers Arun Shukla, an expert in blast mitigation who regularly advises the U.S. Navy, and Akash Pandey, a Ph.D. candidate whose work focuses on materials capable of withstanding underwater blasts.

Shukla’s lab has equipment capable of producing industrial-scale shock loading, but none of it was suitable for delicate cell-based experiments. The team needed something smaller, safer, cheaper, and biologically compatible—something that could sit on a lab table.

Pandey took on the challenge during the summer of 2024. Within a month, he had designed, built, and calibrated a miniaturized shock tube specifically tuned for biological use. Meanwhile, Sirtori developed and carried out the biological experiments, exposing lab-grown organoids to carefully controlled blast waves.

What started as an unlikely partnership between cell biologists and engineers turned into a compact and reproducible blast simulator that any reasonably equipped biology lab could build.

What the Device Actually Does

The tabletop device can create high-pressure pulses delivered in under one millisecond—around 100 times faster than a blink. Despite the extremely short exposure, this rapid overpressure is enough to cause severe structural damage inside human brain organoids.

In their prototype tests:

- Organoids were exposed to a brief pressure wave representing an explosive blast.

- Even this single exposure led to significant cellular damage.

- The nature of the injury closely resembles what is seen in real blast-related TBI.

The device enabled researchers to identify that deep-layer cortical neurons are more vulnerable to blast forces than neurons in upper layers. This level of fine detail is difficult to observe using animal models alone.

The team also plans to use the system to investigate DNA damage, which is a critical factor in the long-term progression of neurodegenerative diseases following TBI.

Why This Is a Big Deal for TBI Research

A blast simulator made from inexpensive components may seem deceptively simple, but it solves a substantial bottleneck in the field.

Here are some major advantages:

- Accessibility: Labs without specialized engineering infrastructure can now study blast TBI.

- Human relevance: Using human-iPSC-derived organoids reduces reliance on animal models, which often fail to fully mimic human injury responses.

- Customization: Pressure intensity and duration can be adjusted depending on research needs.

- Reproducibility: The system provides a controlled and consistent blast profile.

- Cost-effectiveness: Materials are easy to obtain and inexpensive, which could democratize TBI research globally.

Fallini noted that the invention gave her team a new way to examine neurodegeneration risks, and she also appreciated the chance to see the engineering side of blast research—work that normally looks very different from traditional cell biology.

How This Fits Into the Bigger Picture of TBI & Neurodegeneration

TBI is widely recognized as one of the most important environmental risk factors for later-life neurodegenerative conditions. The connection between blast injuries and diseases such as Alzheimer’s or ALS has been reinforced by epidemiological data, but the specific cellular mechanisms that link the two remain poorly understood.

Organoid research is changing that.

Because organoids are derived from human stem cells, they provide models that exhibit aspects of human brain development, layering, gene expression, and even early circuit formation. Studying blast injury in this context allows researchers to track:

- changes to cellular structures,

- alterations in gene expression,

- mitochondrial damage,

- protein misfolding,

- inflammatory responses, and

- long-term degeneration patterns.

Scientists still face limitations. Organoids lack blood vessels, immune cells, and the full structural complexity of a real brain. But they capture molecular events with a level of human relevance that animal models simply cannot match.

With the addition of a portable, reproducible blast device, researchers can now explore how mechanical trauma triggers cascades of damage that may eventually contribute to chronic neurological decline.

Additional Background: The Science of Blast-Induced TBI

Blast-induced TBI is different from other forms of head trauma. Instead of the brain being physically hit or shaken, the damage results from a rapid overpressure wave passing through the skull and brain tissue.

Key characteristics:

- Primary blast injury is caused by the pressure wave itself.

- Secondary and tertiary effects (shrapnel, bodily displacement) are also dangerous but are different mechanisms.

- Pressure waves can cause microscopic tearing, membrane disruption, axonal injury, and vascular damage.

- Even low-level or repeated blasts can cause cumulative harm.

Understanding these mechanisms is essential for improving treatment strategies for military personnel, veterans, and civilians exposed to explosions or weapon firing.

The new device contributes to this growing area of research by offering a controlled way to study the primary mechanical effect of blasts directly on human-derived neural tissue.

Looking Ahead

The URI team’s invention is not just a clever engineering solution—it is a standardized and customizable tool that can help researchers around the world investigate TBI more accurately and more efficiently. Whether the goal is to evaluate DNA damage, test neuroprotective therapies, or better understand why some neurons are more vulnerable than others, this tabletop blast simulator opens doors that were previously shut by cost and equipment limitations.

It also serves as a reminder that innovation doesn’t always come from high-tech machinery. Sometimes, it comes from a small team, a creative idea, and a handful of affordable materials.

Research Paper:

A Tabletop Blast Device for the Study of the Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury on Brain Organoids

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2025.101213