A Newly Identified Molecular Switch Helps Breast Cancer Cells Survive Harsh Conditions

Researchers have uncovered a detailed molecular mechanism that explains how breast cancer cells adapt and thrive in stressful environments that would normally threaten their survival. This mechanism centers on a key transcriptional regulator called MED1, whose chemical state acts like a molecular switch, allowing cancer cells to rapidly adjust gene expression during environmental stress. The discovery, made by scientists at Rockefeller University and published in Nature Chemical Biology, reveals how cancer cells repurpose an essential transcriptional complex to support tumor growth, stress tolerance, and treatment resistance.

Understanding the Core Discovery

At the heart of this study is RNA polymerase II, often called Pol II—the main enzyme responsible for transcribing protein-coding genes. Pol II works closely with a massive protein assembly known as the Mediator complex, which contains 30 subunits and helps activate transcription. One of those subunits, MED1, plays an especially crucial role in directing Pol II activity.

MED1 is known to be vital in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer (ER+ BC), a subtype where estrogen receptor signaling drives tumor growth. Previous research from the same lab showed that interactions between MED1 and estrogen receptors can make certain breast cancers resistant to drugs. That led researchers to wonder whether MED1 might also influence how cancer cells survive stressful conditions like low oxygen, oxidative stress, or temperature fluctuations.

Their investigation uncovered a specific type of biochemical modification—acetylation—that dynamically toggles MED1’s behavior. Acetylation involves adding an acetyl group to a protein; deacetylation removes it. These modifications are already known to shape cancer development, metastasis, and drug response, but their impact on MED1 had not been studied in depth.

How Stress Triggers a Molecular Shift

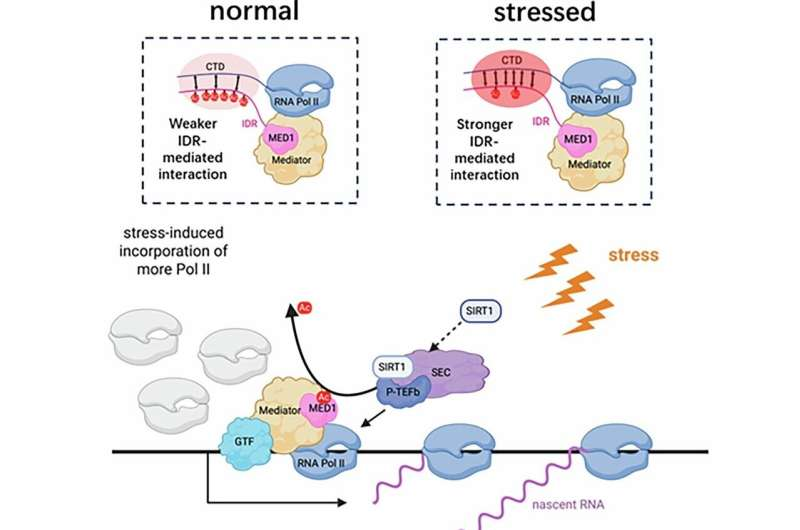

The researchers found that under normal conditions, MED1 carries multiple acetyl groups. But when cells encounter stress, a protein called SIRT1—a well-known deacetylase—removes these acetyl groups. SIRT1 performs this action while associated with the super elongation complex (SEC), positioning it near the transcription machinery.

Removing the acetyl groups causes MED1 to change the way it interacts with Pol II. Specifically, its intrinsically disordered region (IDR) forms stronger connections with the Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD). This enhanced interaction increases Pol II’s incorporation at gene promoter regions, boosting the activation of genes that help cells cope with harmful conditions.

To test how important acetylation is, researchers engineered a version of MED1 lacking six specific acetylation sites. This mutant MED1 cannot be acetylated under any circumstances. When they introduced it into breast cancer cells—after removing the normal MED1 using CRISPR—they found that the cells behaved as though they were permanently in a stress-adapted state. These cells produced fast-growing and highly stress-resistant tumors, both in culture and in mouse models.

The conclusion was clear: whether through natural stress-induced deacetylation or genetic removal of acetylation sites, MED1 shifts cancer cells into a mode that supports survival and growth under harsh conditions. This effectively acts as a regulatory switch that reprograms transcription.

Why This Finding Matters

This mechanism explains something long observed but not fully understood: cancer cells often thrive in environments that are naturally hostile. Tumors suffer from low oxygen, poor nutrient supply, oxidative damage, and immune pressure. Yet cancer cells often use these disadvantages as fuel for aggression.

By identifying the MED1 switch, scientists now have a clearer view of how cancer cells convert stress into opportunity. Importantly, the pathway may be targetable. Blocking MED1’s deacetylation or its enhanced interaction with Pol II may make cancer cells more vulnerable to therapies, especially those that rely on inducing cellular stress.

Because MED1 is a component of a generic transcription system, this research also provides a glimpse into how normal cellular machinery can be repurposed for harmful processes like tumor progression. MED1 isn’t the only protein regulated by acetylation; similar mechanisms have been observed in transcription factors like p53, pointing toward a more general paradigm in gene regulation.

Broader Context: Why Transcriptional Stress Adaptation Matters in Cancer

Cancer cells constantly face environmental pressures caused by their rapid growth. Solid tumors frequently develop regions of hypoxia, oxidative imbalance, and nutrient deprivation. When normal cells experience these conditions, they may slow growth or initiate cell death pathways. Cancer cells, however, thrive through a mix of genetic mutations and epigenetic or post-translational changes like those seen in MED1.

Several stress-response pathways are already well-known in cancer biology:

- HIF-1α stabilization under hypoxia promotes angiogenesis and metabolic rewiring.

- NF-κB activation under inflammatory or oxidative stress boosts survival signaling.

- Heat shock proteins prevent protein damage and support malignant growth.

- Unfolded protein response (UPR) enables tumor cells to survive endoplasmic reticulum stress.

The newly uncovered MED1-dependent mechanism adds another layer: transcriptional reprogramming via Pol II recruitment, which directly adjusts the genes necessary for stress survival.

The integration of these pathways helps explain why cancer cells are so adaptable. They don’t just mutate; they actively redirect basic cell machinery to support malignant behavior.

MED1 and Estrogen Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer

This research is especially relevant for ER+ breast cancer, one of the most common forms of breast cancer. In ER+ tumors:

- Estrogen receptor signaling heavily relies on MED1, making MED1 a pivotal player in gene activation.

- MED1’s involvement has been linked to resistance to endocrine therapies, including tamoxifen.

If cancer cells also rely on MED1 to survive stress, it means the same protein helps tumors resist both environmental challenges and drug treatment. This dual role makes MED1 a highly appealing target for future therapies.

Future Directions and Research Possibilities

The study leaves several interesting questions open:

- Does this mechanism function the same way in other cancer types, or is it primarily a feature of ER+ breast cancer?

- Are there small molecules that can prevent MED1 deacetylation or block its interaction with Pol II?

- Can targeting this pathway increase the effectiveness of therapies that induce stress, such as chemotherapy or radiation?

- Do normal cells use this switch during physiological stress, or is it uniquely exploited by cancer?

Understanding these questions may open entirely new therapeutic avenues.

The Value of Studying Basic Gene Regulation

Although this discovery centers on cancer, it also highlights a broader truth: studying basic molecular biology often leads to unexpected breakthroughs. MED1 and Pol II are fundamental components of gene transcription, essential in almost every human cell. By understanding the fine details of how they operate, researchers can uncover mechanisms that diseases like cancer hijack for their own advantage.

This reinforces why foundational research remains crucial. Many therapeutic insights—such as the role of acetylation in regulating transcription factors—come from exploring how the cell works at the most fundamental level.

Research Paper

MED1 IDR deacetylation controls stress responsive genes through RNA Pol II recruitment