Aerobic Exercise Emerges as the Best Remedy for Knee Osteoarthritis Pain, Says Major BMJ Study

A new systematic review and meta-analysis published in The BMJ has delivered one of the most comprehensive answers yet to a question that has puzzled both doctors and patients for years — what kind of exercise works best for knee osteoarthritis?

According to the research team, aerobic exercises like walking, cycling, and swimming appear to be the most effective ways to reduce pain, improve mobility, and boost overall quality of life in people living with knee osteoarthritis (KOA). The findings come from an analysis of 217 randomized controlled trials involving 15,684 participants, making it one of the largest studies ever conducted on the topic.

The results not only highlight the power of regular movement but also bring much-needed clarity to treatment plans, helping doctors and patients understand which forms of physical activity actually make a measurable difference.

Understanding Knee Osteoarthritis

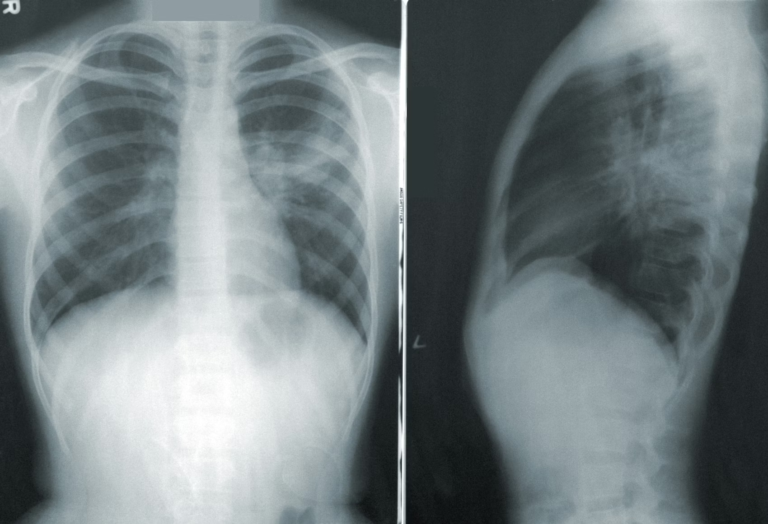

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis and a major cause of disability worldwide. It occurs when the protective cartilage that cushions the ends of bones gradually wears down, leading to pain, swelling, stiffness, and reduced motion.

Although the condition can affect any joint, the knee is particularly vulnerable because it bears much of the body’s weight. In fact, around 30% of adults over 45 show signs of knee osteoarthritis on X-rays, and about half of them experience chronic pain.

Common symptoms include:

- Persistent knee pain that worsens with movement

- Stiffness, especially after sitting or sleeping

- Popping or cracking sounds

- Swelling or tenderness

- Reduced flexibility and difficulty walking

While there’s no cure, exercise remains a cornerstone of management. But medical guidelines have long been vague about which type of exercise works best — strengthening, flexibility, or aerobic training. This new BMJ study sought to clear up that uncertainty once and for all.

What the Study Looked At

The team behind the study — led by Lei Yan and colleagues from several Chinese institutions and international collaborators — conducted a network meta-analysis, which allows researchers to compare multiple interventions even when some haven’t been directly compared in trials.

They gathered data from major medical databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and others, covering research published from 1990 to 2024.

To qualify for inclusion, studies had to be randomized controlled trials involving adults with knee osteoarthritis. The exercises analyzed were grouped into six main categories:

- Aerobic exercise – activities like walking, running, cycling, swimming

- Strengthening exercise – targeted muscle-building routines

- Flexibility exercise – stretching and range-of-motion workouts

- Mind-body exercise – practices like yoga and Tai Chi

- Neuromotor exercise – balance and coordination training

- Mixed exercise – combinations of the above

Each intervention was compared to a control group (often those receiving usual care or no exercise intervention).

Researchers evaluated how these exercise types influenced four key outcomes:

- Pain reduction

- Functional ability (everyday movement and activity)

- Walking performance (gait tests)

- Quality of life

The effects were measured across short-term (4 weeks), mid-term (12 weeks), and long-term (24 weeks) follow-up periods. To assess reliability, the team applied the GRADE system, a well-known framework for rating the certainty of scientific evidence.

The Clear Winner: Aerobic Exercise

The study found that aerobic exercise consistently ranked as the top performer across nearly every category — pain relief, functional improvement, walking ability, and overall quality of life.

Specifically, aerobic exercise “probably results in large improvements” in:

- Short-term pain (standardized mean difference, or SMD, −1.10)

- Mid-term pain (SMD −1.19)

- Mid-term function (SMD 1.78)

In simpler terms, people who engaged in regular aerobic activity experienced noticeably less pain and better mobility over both short and medium timeframes.

Interestingly, other exercise types also showed meaningful — though smaller — benefits:

- Mind-body exercises (like yoga or Tai Chi) likely lead to major short-term improvements in functional ability (SMD 0.88).

- Neuromotor training showed the biggest gains in walking performance (SMD 1.04).

- Strength training and mixed exercise programs contributed to mid-term functional improvements (SMDs of 0.86 and 1.07, respectively).

None of the exercise types caused more adverse events than control groups, confirming that exercise is a safe and low-risk therapy for knee osteoarthritis.

How Reliable Is the Evidence?

The researchers were careful to acknowledge several limitations:

- Indirect comparisons: Many of the results were drawn from network connections rather than direct head-to-head studies. This can slightly lower the precision of the findings.

- Limited long-term data: Most trials tracked patients for less than six months. Long-term effectiveness remains less clear.

- Small-study effects: Smaller trials sometimes showed stronger effects than larger ones, suggesting a possible publication bias.

- Varied patient groups: The included studies involved people with different severities of osteoarthritis, exercise regimens, and baseline fitness levels, which introduces heterogeneity.

- Lack of dosage clarity: The analysis didn’t specify optimal duration, frequency, or intensity for aerobic exercise — questions future research could explore.

Even with these caveats, the moderate certainty of evidence gives clinicians and patients strong confidence that aerobic exercise should be the first-line non-drug intervention for managing knee osteoarthritis.

Why Aerobic Exercise Works So Well

Aerobic activity improves more than just muscle tone — it influences the entire joint environment. Here’s why it helps:

- Increased blood flow: Boosts nutrient delivery to joint tissues and helps flush out inflammatory substances.

- Reduced inflammation: Regular movement helps lower inflammatory markers that contribute to cartilage breakdown.

- Weight control: Many people with knee osteoarthritis are overweight, and even a 10% reduction in body weight can significantly reduce knee load and pain.

- Improved mood and sleep: Pain perception is closely tied to mental health. Aerobic activity releases endorphins, reducing pain sensitivity and improving mood.

- Better neuromuscular control: Continuous movement helps retrain how the brain and muscles coordinate knee stability and movement.

This comprehensive effect explains why walking, cycling, and swimming outperform isolated strengthening or stretching exercises in large populations.

The Role of Other Exercise Types

Although aerobic exercise topped the list, the researchers emphasized that other forms of structured exercise remain valuable.

- Strength training supports joint stability by building up the quadriceps and hamstrings, which help absorb shock and reduce joint stress.

- Flexibility routines preserve range of motion, making everyday tasks easier.

- Mind-body practices like Tai Chi improve balance and mindfulness, reducing fall risk and anxiety related to pain.

- Neuromotor training — which focuses on balance, agility, and coordination — helps restore proper movement patterns that can deteriorate over years of knee pain.

The takeaway? Even if aerobic exercise is the backbone of treatment, combining multiple exercise types can address different aspects of the condition.

What This Means for Patients and Doctors

For patients, the message is clear: keep moving. Aerobic exercise — especially low-impact forms like walking, cycling, and swimming — should be viewed as a first-choice therapy, not just an optional addition.

For healthcare providers, this study provides strong evidence to tailor treatment plans. Aerobic exercise should be recommended early and consistently, with adaptations for individual ability and preference.

If someone cannot engage in traditional aerobic workouts due to pain or mobility limitations, alternative forms like Tai Chi or water-based exercise still offer meaningful benefits.

Importantly, these interventions are safe and carry minimal risk of side effects compared to medication or surgery.

Broader Implications for Public Health

With knee osteoarthritis affecting hundreds of millions globally, the study’s message extends beyond the clinic. Encouraging older adults to stay physically active could significantly reduce the burden of disability, healthcare costs, and lost productivity.

Public health initiatives that promote accessible exercise programs, such as community walking groups or local pool sessions for older adults, could play a key role in long-term joint health.

Additionally, this study strengthens the case for non-pharmacological interventions as the foundation of osteoarthritis management — a shift away from over-reliance on painkillers and invasive procedures.

Takeaway for Readers

If you or someone you know struggles with knee osteoarthritis, the science is now clearer than ever:

- Move regularly — even small amounts of aerobic activity make a measurable difference.

- Start slow, build steadily — consistent, moderate-intensity exercise is safer and more sustainable than sporadic bursts.

- Mix it up — combine aerobic, strengthening, and flexibility work for the best long-term results.

- Listen to your body — discomfort is normal, but sharp pain means you should ease up.

Remember, exercise isn’t just a treatment — it’s a form of medicine for your joints, and the side effects are all positive.