Aging Midbrain Dopamine Neurons Face an Energy Crisis That May Explain Parkinson’s Disease Progression

Scientists have uncovered an important clue about why certain brain cells gradually fail with age and why their loss is so central to Parkinson’s disease. New research from Weill Cornell Medicine shows that midbrain dopamine neurons, which are essential for movement, learning, and motivation, face a growing energy crisis as they age. This metabolic vulnerability may help explain why these neurons are especially prone to degeneration in Parkinson’s disease.

The study, published in December 2025 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focuses on dopamine-producing neurons located in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra pars compacta. These neurons are famous for their role in controlling voluntary movement, and their gradual loss is responsible for the hallmark symptoms of Parkinson’s, including muscle stiffness, tremors, and slowed motion.

Why Midbrain Dopamine Neurons Are Unusually Demanding

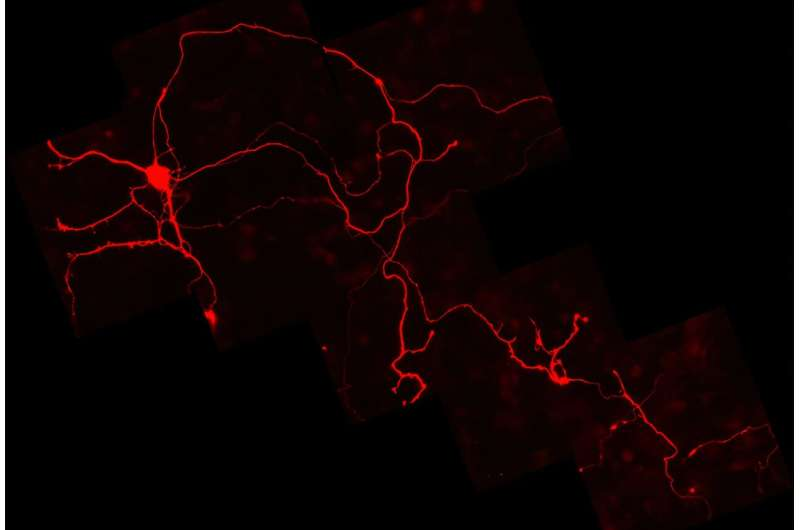

Midbrain dopamine neurons are not ordinary brain cells. They have exceptionally long and complex branching structures, meaning a single neuron can send signals to many distant regions of the brain. Maintaining these extensive networks requires a constant and very high supply of energy.

Under normal conditions, neurons rely almost entirely on glucose delivered through the bloodstream. Any disruption to this supply can threaten their ability to function. For years, scientists believed that neurons lacked the ability to store backup energy, unlike muscle or liver cells. This assumption made the resilience of dopamine neurons during brief glucose shortages something of a mystery.

A Surprising Discovery: Neurons Store Glycogen

The new research overturns a long-standing belief in neuroscience. The researchers demonstrated, for the first time directly, that dopamine neurons can store glycogen, a compact form of glucose made up of clustered sugar molecules.

Using a specialized antibody designed to detect glycogen, the team observed glycogen deposits inside dopamine neurons, including in their axon terminals, where signals are transmitted to other cells. This finding is significant because glycogen storage allows neurons to keep functioning even when their normal glucose supply is temporarily interrupted.

In laboratory experiments using rat midbrain dopamine neurons, the researchers found that these cells could continue operating for surprisingly long periods without external glucose. This endurance strongly depended on their internal glycogen reserves.

How Dopamine Regulates Its Own Energy Supply

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study is how dopamine neurons regulate their glycogen storage. The researchers discovered that these neurons use dopamine-sensing D2 receptors located on their own output terminals to control how much glycogen they produce and store.

In simple terms, dopamine output directly influences energy reserves. When dopamine release is high, D2 receptor activity increases, signaling the neuron to build up larger glycogen stores. When dopamine output drops, glycogen production falls as well.

This feedback system creates a dangerous vulnerability. If dopamine signaling begins to decline, glycogen storage also decreases. With fewer energy reserves available, neurons become extremely sensitive to glucose shortages. Once glycogen is depleted, even brief interruptions in glucose supply can cause the neurons to stop functioning almost immediately.

Aging Turns Vulnerability Into a Downward Spiral

The researchers propose that aging plays a critical role in pushing dopamine neurons into this metabolic danger zone. Evidence already suggests that dopamine neuron function gradually declines with normal aging, even in people who never develop Parkinson’s disease.

As dopamine output diminishes over time, glycogen storage also decreases. This leaves neurons less resilient to everyday metabolic stress. According to the researchers, this process may create a self-reinforcing downward spiral, where declining dopamine signaling leads to energy failure, which further worsens neuron function and ultimately leads to cell death.

This model fits well with Parkinson’s disease, where dopamine neurons degenerate progressively rather than all at once.

Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors Fit the Picture

The study’s findings also align with what scientists already know about Parkinson’s disease genetics. Many gene mutations linked to Parkinson’s affect cellular energy production, mitochondrial function, or fuel transport. These defects would further reduce the ability of dopamine neurons to cope with energy stress.

Environmental factors may also play a role. Toxins, inflammation, and oxidative stress can all interfere with cellular metabolism. In neurons that are already operating near their energy limits, these additional stressors may be enough to tip the balance toward degeneration.

Medication Side Effects Offer Additional Clues

An interesting real-world observation supports the researchers’ hypothesis. Some antipsychotic medications block D2 dopamine receptors as part of their therapeutic effect. These drugs are known to sometimes cause Parkinson’s-like movement symptoms as side effects.

The new findings suggest a possible explanation. By reducing D2 receptor activity, these medications may also reduce glycogen storage in dopamine neurons, lowering their energy resilience and impairing normal motor function.

What This Means for Parkinson’s Research and Treatment

Most current Parkinson’s treatments focus on replacing dopamine or mimicking its effects, which helps manage symptoms but does not stop neuron loss. This study points toward a different strategy: protecting the energy resilience of dopamine neurons.

If scientists can find ways to support glycogen storage, improve glucose utilization, or enhance overall metabolic stability in these neurons, it may be possible to slow disease progression or even prevent Parkinson’s from developing in at-risk individuals.

While such therapies are still speculative, the findings open a new and promising direction for future research.

Expanding the Question Beyond Dopamine Neurons

The researchers are not stopping with midbrain dopamine neurons. Their next goal is to examine glycogen storage in other neuron populations throughout the nervous system.

Different types of neurons have different energy demands, firing patterns, and vulnerabilities. Understanding how glycogen storage varies across the brain could reshape how scientists think about energy failure in neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, and other age-related conditions.

Why Energy Failure Is a Growing Theme in Neurology

This study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that energy insufficiency is a common failure mode in brain disorders. Neurons are among the most energy-demanding cells in the body, and even small disruptions in fuel supply can have dramatic consequences.

By showing that neurons do have energy reserves—but regulate them in risky ways—the research bridges a gap between metabolic biology and neurodegeneration. It suggests that Parkinson’s disease may not be caused by a single toxic event, but rather by a gradual erosion of metabolic safety margins over decades.

A New Way of Thinking About Neuron Survival

The idea that dopamine neurons die because they run out of usable energy, rather than simply being poisoned or genetically doomed, offers a more nuanced and hopeful view of Parkinson’s disease. Energy crises can potentially be prevented, delayed, or mitigated.

As researchers continue to explore how neurons manage their fuel supplies, this work may ultimately help shift Parkinson’s research toward earlier interventions focused on cellular resilience, long before symptoms appear.

Research paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2523019122