AI-Powered Virtual Humans Could Transform How We Discover New Drugs

Researchers at Northeastern University are working on a concept that could dramatically change how new medicines are developed: AI-powered programmable virtual humans. This idea, introduced by professor Lei Xie and researcher You Wu, aims to shift drug discovery away from the slow, expensive, and failure-ridden traditional model and toward a system where scientists can test how a brand-new compound behaves across an entire human body—without ever exposing it to actual humans or animals. Their proposal recently appeared in Drug Discovery Today and builds on years of work involving AI, biological modeling, and large-scale data integration.

The Long and Difficult Road of Traditional Drug Development

Bringing a single drug to market usually takes 10 to 15 years, costs billions of dollars, and still fails about 90% of the time. That staggering failure rate comes from how early testing is conducted. Most early-stage experiments try to understand what a compound does to a specific gene or protein, often inside a dish or in an animal model.

The problem is straightforward: a test tube or mouse is not a human. Even when a compound behaves perfectly in a controlled lab setup, that doesn’t mean it will behave the same way inside the complex network of systems that make up the human body. These early tests also ignore the countless interactions a drug might trigger—changes in gene expression, shifts in protein levels, off-target effects, metabolic consequences, and unexpected impacts on tissues or organs that weren’t the original focus.

Because of this mismatch between early experiments and real human biology, many drugs reach late-stage trials before failing due to toxicity, low effectiveness, or unforeseen side effects. Xie argues that this isn’t a problem AI can solve simply by speeding up existing steps. Instead, he believes the entire paradigm of drug discovery needs updating.

What a Programmable Virtual Human Actually Does

The team’s proposed virtual human is inspired by, but distinct from, the growing concept of a pharmacological digital twin. Digital twins usually model how an existing drug works based on past data—information from previous trials, approved drugs, or similar molecules. But the researchers want something more ambitious: a model capable of predicting how a drug that no one has ever tested before would behave inside the human body.

To achieve this, the virtual human combines two core components:

- Physics-based models built from biological, physiological, and clinical knowledge

- Machine-learning models trained on large datasets describing how human systems behave under different conditions

Together, these tools allow the virtual human to simulate how a compound interacts with molecules, proteins, DNA, RNA, cells, tissues, organs, and body-wide processes. The system doesn’t stop at the drug’s primary target. Instead, it evaluates ripple effects across the entire biological landscape.

The researchers say this approach could be especially useful for diseases involving multiple interacting genes, such as Alzheimer’s disease, certain neurological disorders, and complex or rare conditions with few existing treatments.

Why This Model Could Change Drug Discovery

If successful, this virtual human simulation could help scientists answer critical questions long before a drug reaches clinical trials:

- Are there potential side effects?

- Could the compound be toxic at certain doses?

- Does the drug activate or suppress important biological pathways unintentionally?

- Is the compound likely to be effective in real human tissue rather than just in a petri dish?

By predicting these outcomes early, researchers could dramatically reduce the number of compounds that reach expensive trial phases only to fail. Pharmaceutical companies could save vast amounts of money and time, and more promising drugs could reach patients faster.

Why This Isn’t Ready Yet

While early tests of the concept are encouraging, the researchers stress that the system is still far from widespread deployment. Several major challenges remain:

- Huge amounts of biological and clinical data must be gathered and integrated.

- Multiple complex models—spanning molecular biology to whole-body physiology—must be combined.

- Collaboration between universities, biotech companies, and government agencies will be necessary.

- Significant funding and computational resources must be secured.

Still, Xie notes that they are actively progressing toward these goals. The work so far demonstrates that this ambitious idea is not just theoretical; the foundations are already taking shape.

A Shift in How We Think About Discovery

The researchers emphasize that this concept isn’t simply an advanced use of AI. Instead, it represents a shift in mindset. Instead of viewing drug discovery as the search for a molecule that binds to a single target, this new approach considers the body as a dynamic system where thousands of processes interact. Understanding how a drug influences the system as a whole—rather than just one isolated part—could redefine what “drug discovery” means in the first place.

According to Xie, true innovation won’t come from AI acting as a faster calculator. It will come from AI helping us understand how the entire human system responds to treatment. That is the promise behind programmable virtual humans: a framework that reasons across biological levels and ties together molecular science, systems biology, and computational intelligence.

Extra Context: The Growing Field of Digital Biology

The concept of a virtual human doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It fits into the rapidly expanding field of digital biology, where researchers use computational models to understand, simulate, and predict biological behavior. Here are a few notable areas related to this work:

Digital Twins in Medicine

Some hospitals and biomedical companies already use digital twins to simulate heart function, metabolism, or disease progression in individual patients. These models personalize treatment plans or predict how a patient might respond to a specific therapy. While impressive, these current tools generally simulate specific organs or conditions, not the entire human system.

AI in Drug Design

AI is increasingly used to design new molecules, predict protein structures, and filter out compounds likely to fail. Platforms built by pharmaceutical companies and AI labs are speeding up early-stage discovery, but they typically focus on molecular modeling, not whole-body simulation.

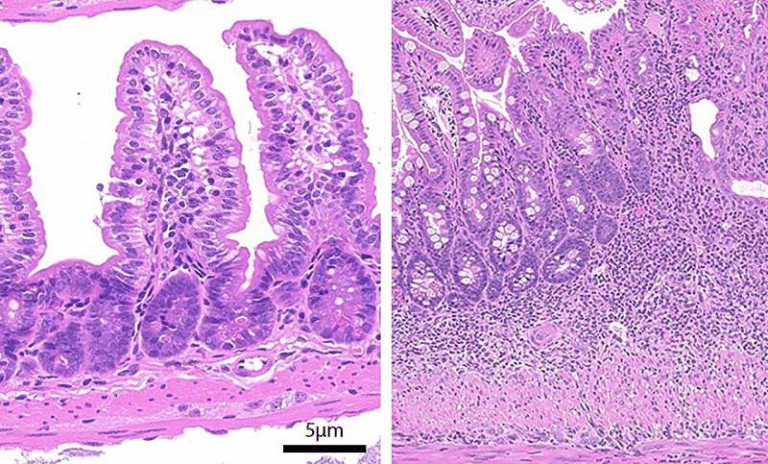

Systems Biology

This field studies how biological components—genes, proteins, pathways—interact across scales. The virtual human concept draws heavily from systems biology by trying to capture interconnected biological networks rather than isolated parts.

Combining these three domains—digital twins, AI drug modeling, and systems biology—brings us closer to a future where biomedical research operates as much in silico as in the lab.

Looking Ahead

A future where researchers test drugs on virtual humans before real ones might sound futuristic, but according to the Northeastern team, the foundations already exist. What’s needed now is continued technological development, large-scale data gathering, collaboration across scientific communities, and support from regulatory agencies willing to consider new testing paradigms.

If these challenges are overcome, programmable virtual humans could help deliver safer drugs, reduce research costs, and open possibilities for treating complex diseases that have long resisted traditional approaches.

Research Paper:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359644625002107