B Cells Play a More Sinister Role Than Believed in the Progression of Type 1 Diabetes

New research from Vanderbilt University Medical Center is reshaping how scientists understand the immune processes behind type 1 diabetes (T1D). For years, B lymphocytes, commonly known as B cells, were considered supporting players in the autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells. This latest study suggests something far more troubling: B cells may actively sabotage the immune system’s own regulatory defenses, accelerating the progression of the disease.

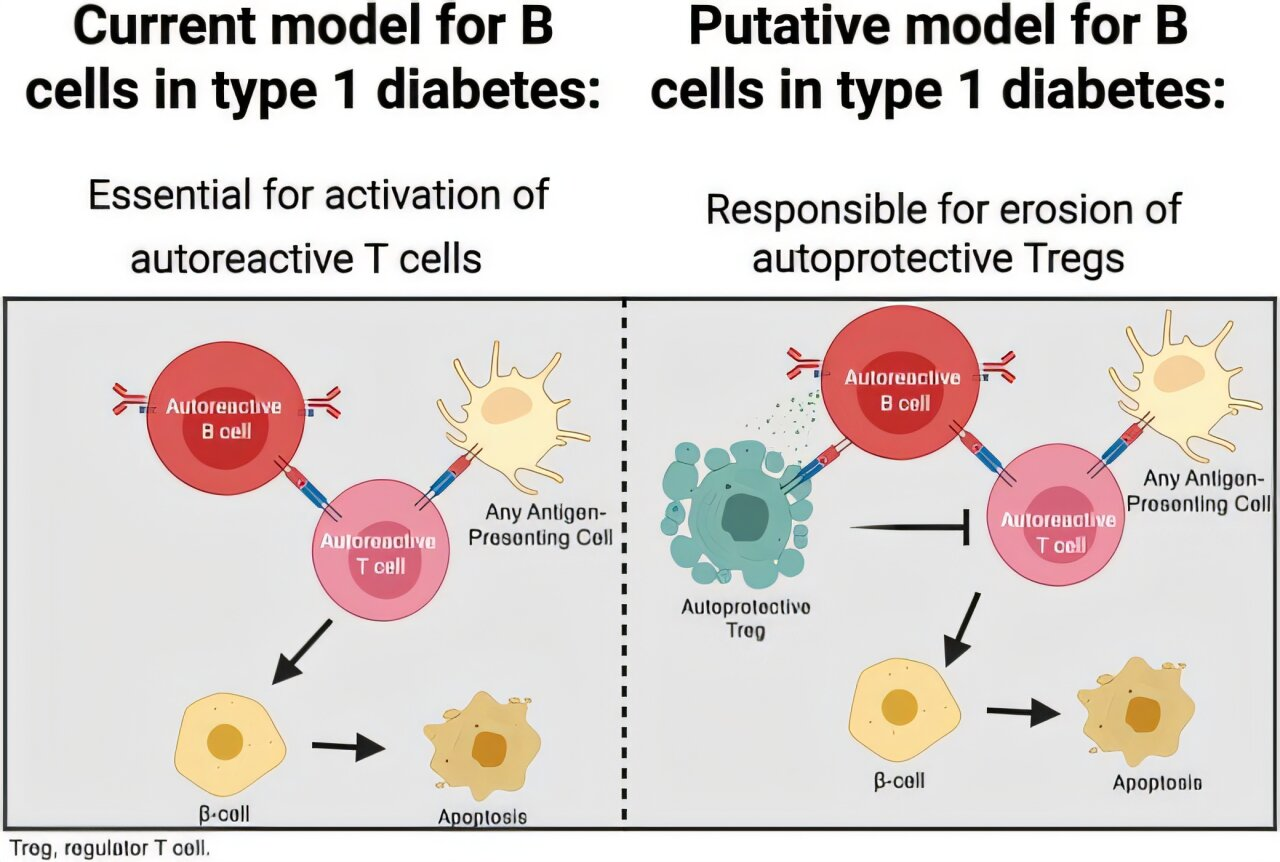

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the beta cells of the pancreas, leading to a lifelong dependence on insulin therapy. Much of the research focus has traditionally been on T cells, which directly attack these beta cells. B cells, meanwhile, were thought to play a secondary role by producing autoantibodies or by helping activate aggressive T cells. The new findings suggest this view was incomplete.

A Deeper Look at What B Cells Are Doing

The study, conducted by researchers at Vanderbilt Health and published in the journal Diabetes, reveals that B cells do more than just help initiate immune attacks. They also interfere with regulatory T cells, or Tregs, which are essential for keeping the immune system in check.

Tregs act as the immune system’s internal moderators. Their job is to suppress excessive immune responses and prevent the body from attacking its own tissues. In the context of type 1 diabetes, Tregs help protect pancreatic beta cells from autoimmune destruction. The Vanderbilt researchers found that B cells actively limit both the development and effectiveness of these protective Tregs.

This means that B cells are not just indirectly involved in the disease process. They are actively weakening the body’s natural ability to regulate immune responses, tipping the balance toward destructive autoimmunity.

What the Mouse Models Revealed

To uncover this mechanism, the researchers relied on several carefully designed mouse models of type 1 diabetes. These models allowed them to observe how the immune system behaves when B cells are present versus when they are absent.

In mice that lacked B cells, the results were striking. Regulatory T cells were stronger, more numerous, and more effective. These mice showed enhanced expansion of Tregs and a healthier immune balance overall. Specifically, there was an increased ratio of insulin-reactive Tregs compared to activated or effector T cells that promote inflammation and tissue damage.

One of the most compelling findings involved pancreatic islet transplantation. In B-cell-deficient mice, transplanted insulin-producing pancreatic tissue survived significantly longer. This durable islet transplant tolerance suggests that without B cells interfering, Tregs are better able to protect insulin-producing cells from immune attack.

How the Research Was Conducted

The study used a combination of advanced immunological techniques to analyze immune cell populations and their behavior. These included flow cytometry to identify and quantify immune cells, magnetic-activated cell sorting to isolate specific cell types, and immunohistochemistry to visualize immune cells within tissues.

By applying these methods, the researchers were able to precisely measure how B cells affected Treg populations and their functional capacity. The results consistently pointed to the same conclusion: B lymphocytes accelerate destructive immune responses by negatively regulating Treg development and function.

A Shift in How Scientists View B Cells

This research represents a meaningful shift in how B cells are viewed in the context of type 1 diabetes. Rather than being simple accomplices that help activate harmful T cells, B cells appear to be active saboteurs of immune regulation.

The researchers emphasize that this new understanding could influence how scientists think about immune tolerance more broadly. The interference of B cells with Tregs may not be limited to type 1 diabetes. Similar mechanisms could be at work in other autoimmune diseases, making this an important area for further investigation.

Implications for Future Therapies

One of the most promising aspects of this discovery lies in its therapeutic potential. Current immunotherapies for type 1 diabetes often focus on broadly suppressing the immune system or targeting T cells directly. These approaches can be effective but may also carry risks, such as increased susceptibility to infections.

Targeting B cell–Treg interactions offers a more selective strategy. The study suggests that interventions aimed at preventing B cells from disrupting Treg function could help preserve beta cells without shutting down the immune system entirely.

The researchers also highlight the thymus gland as a key area of interest. Since the thymus is where T cells develop and are educated, targeting B cell activity in this environment could help promote the development of stronger, more effective regulatory T cells from the outset.

Why Regulatory T Cells Matter So Much

To understand the importance of these findings, it helps to take a closer look at regulatory T cells themselves. Tregs are essential for maintaining immune tolerance, the process that prevents the immune system from attacking the body’s own tissues. When Treg function is impaired, autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes become much more likely.

In healthy individuals, Tregs constantly suppress overactive immune responses. In people at risk for T1D, this balance is disrupted. The Vanderbilt study suggests that B cells play a direct role in creating this imbalance by holding Tregs back.

Strengthening Treg responses has long been a goal in autoimmune research. This study provides a clearer explanation of why that goal has been so difficult to achieve and identifies a specific obstacle that could potentially be removed.

Broader Context in Type 1 Diabetes Research

Over the past decade, scientists have increasingly recognized that type 1 diabetes is driven by a complex network of immune interactions rather than a single cell type. B cells, T cells, cytokines, and antigen-presenting cells all contribute to disease progression.

This study adds an important new layer to that understanding. By showing that B cells directly undermine immune regulation, it helps explain why previous therapies targeting only one part of the immune system have had limited success.

It also reinforces the idea that preserving beta cells, delaying disease onset, or even preventing type 1 diabetes altogether may require precise immune modulation rather than broad immune suppression.

What This Means Going Forward

The findings from Vanderbilt Health suggest that researchers and clinicians may need to rethink how they approach immune regulation in type 1 diabetes. B cells are no longer just secondary players; they are central to the breakdown of immune tolerance.

By focusing future research on how B cells interact with regulatory T cells, scientists hope to develop therapies that better protect insulin-producing cells and improve long-term outcomes for people at risk of or living with type 1 diabetes. There is also growing optimism that these insights could extend beyond diabetes, shedding light on immune dysfunction in other autoimmune conditions.

As research continues, this study stands out as a key step toward a more detailed and accurate picture of how the immune system turns against the body—and how it might be guided back toward balance.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.2337/db25-0241