Brain Cleanup Pathway Offers a Promising New Target for Non-Opioid Chronic Pain Relief

Researchers at the Texas A&M University Health Science Center have uncovered a detailed biological pathway that could change how we think about treating chronic pain. Instead of relying on traditional symptom-suppressing medications like opioids, this new work highlights a mechanism inside the brain that directly influences how pain signals are strengthened or quieted. The discovery centers on autophagy, the cell’s natural housekeeping system, and its connection to specific neural communication proteins in the central amygdala, a brain region involved in emotional processing and pain perception.

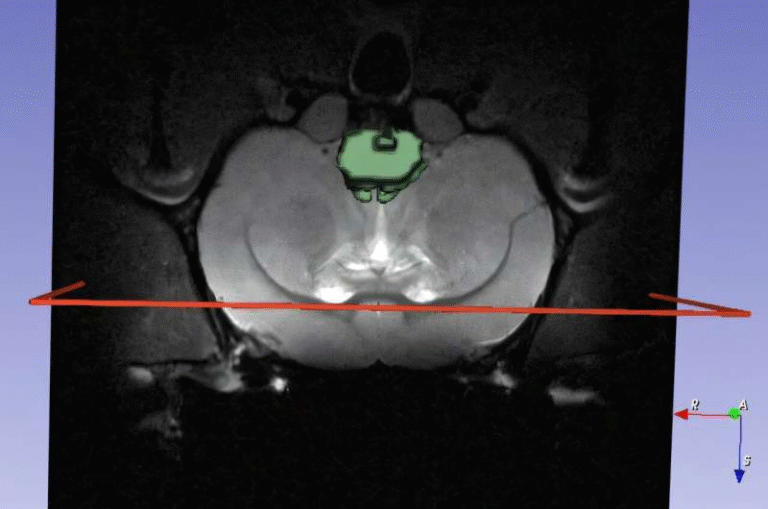

Chronic pain affects an estimated 24.3% of U.S. adults, interfering with daily life and often persisting despite current treatment options. The Texas A&M team, led by neuroscientist Shashank M. Dravid, focused on why certain neurons in the central amygdala become hyperactive during chronic pain and how restoring balance inside those cells may reduce pain.

Understanding the Central Amygdala’s Role in Chronic Pain

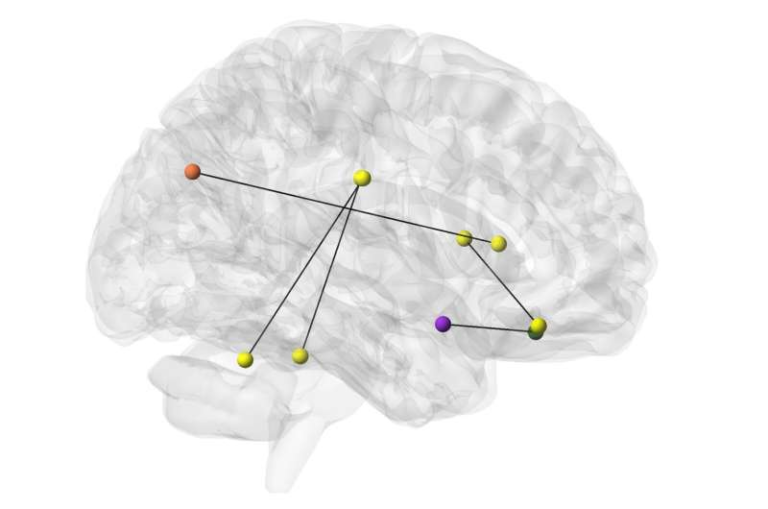

The central amygdala is a crucial hub where emotional and sensory information meets. Neurons in this region communicate through chemical messages passed across synapses, and these messages are detected by receptor proteins on the receiving neuron. The strength of these signals can increase or decrease depending on how many receptors are present at the synapse.

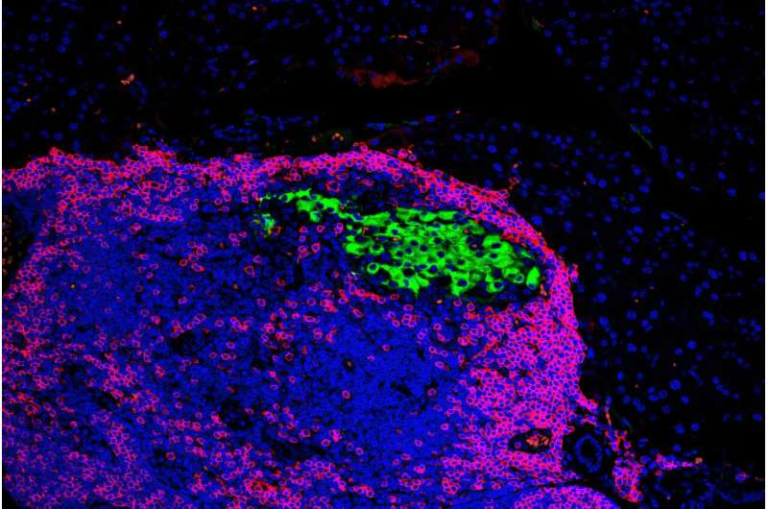

A key receptor in this system is GluD1 (glutamate receptor delta-1). GluD1 connects across the synapse with two other proteins—cerebellin-1 (Cbln1) and neurexin-1α (Nrxn1α)—to create a structural and functional “bridge” between neurons. This bridge helps maintain proper communication and contributes to synaptic plasticity, the brain’s ability to strengthen or weaken connections based on demand.

Previous studies from the Dravid lab showed that GluD1 is deeply involved in the mechanisms of chronic pain. The new research goes further by uncovering how GluD1 influences autophagy inside the very neurons sending and receiving pain signals.

How Disrupted Synaptic Bridges Increase Pain

In chronic pain models, the researchers found that the GluD1-Cbln1-Nrxn1α synaptic bridge becomes disrupted in neurons of the central amygdala. When this bridge weakens, it triggers a chain reaction:

• Autophagy levels drop, meaning the cell becomes less efficient at clearing out old or excess proteins.

• This reduced cleanup causes a buildup of AMPA receptors, another class of glutamate receptors known for amplifying excitatory signalling.

• With more AMPA receptors crowding the neuron’s surface, the neuronal activity becomes stronger and more persistent—essentially turning up the “volume” of pain.

The researchers confirmed that autophagy in these neurons is closely tied to GluD1 levels. They also discovered that GluD1 physically interacts with two well-known autophagy mediators: Beclin-1 and LAMP1. That connection suggests that GluD1 plays a direct regulatory role in the cell’s cleanup machinery.

A shift in synaptic plasticity also becomes evident. Conditions that promote chronic pain tend to favor long-term potentiation (LTP)—a strengthening of synaptic signals—over long-term depression (LTD), which normally helps keep pain signals in check. Increased AMPA receptor activity weakens LTD, removing a key braking mechanism in pain pathways.

Together, these changes help explain why chronic pain becomes entrenched and why traditional medications struggle to correct the underlying neural dysfunction.

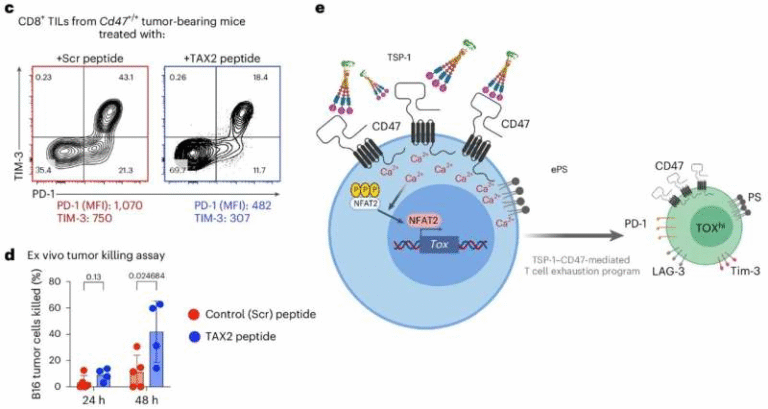

Introducing Tat-HRSPN: A Novel Peptide Designed to Restore Neural Cleanup

To counter this breakdown in communication and cellular housekeeping, the research team developed a new peptide molecule called Tat-HRSPN. The name comes from the fact that the peptide is based on a portion of GluD1’s C-terminal tail, a region previously identified as important for regulating AMPA receptor behavior.

The idea is straightforward: if the natural synaptic bridge involving GluD1 is weakened during chronic pain, then mimicking part of the GluD1 protein might restore the communication signals and restart the autophagic process.

When the peptide was administered to animal models of chronic pain:

• It reduced pain behaviors within 48 hours, a notably fast response.

• Its effects persisted for at least seven days, which was the full length of the testing period.

• Autophagy markers increased, indicating that the cleanup machinery had been reactivated.

• Levels of AMPA receptors dropped, restoring more balanced synaptic signalling.

This combination—improved autophagy, reduced receptor overload, and decreased neuronal excitability—points toward a potentially powerful non-opioid strategy for managing chronic pain at the cellular level.

Why Targeting Autophagy Represents a Major Shift in Pain Treatment

Most current chronic pain treatments focus on blocking pain signals or reducing inflammation. Opioids, for example, alter perception of pain but do not correct the dysfunctional neural circuits driving chronic pain. They also carry serious risks such as addiction and diminishing effectiveness over time.

What makes the Texas A&M discovery noteworthy is that it identifies a root-level dysfunction inside neurons—impaired autophagy—and shows that restoring that process can dramatically reduce pain. Instead of suppressing symptoms, this approach aims to repair the internal machinery of pain-processing neurons.

If future research confirms similar results in humans, treatments based on synaptic restoration and autophagy regulation could represent a new category of precision pain therapies. These would target specific cell types and pathways in the brain rather than broad systems across the entire body.

Autophagy: A Quick Guide to the Cell’s Cleanup Crew

Since autophagy is central to this research, understanding its role adds useful context.

• Autophagy removes old, damaged, or excess cellular components.

• It helps regulate protein levels at synapses, which is crucial for plasticity.

• Impaired autophagy has already been linked to neurodegenerative conditions, aging, and metabolic diseases.

In neurons, where synaptic balance is essential, autophagy keeps receptor numbers in check and ensures healthy communication. When this cleanup slows down, synapses can become overloaded or dysfunctional—exactly what appears to happen in chronic pain.

The Texas A&M study is important because it connects a specific synaptic protein (GluD1) to autophagy mechanics inside central amygdala neurons. It shows that synaptic signalling and cellular recycling aren’t separate systems but part of a coordinated process.

What Comes Next for This Research

The research team plans to continue evaluating how long Tat-HRSPN remains effective, how it might be delivered in a clinical setting, and whether similar peptides could be engineered to target related pathways.

They also aim to refine their understanding of how disruption of the GluD1-Cbln1-Nrxn1α bridge leads to reduced autophagy. Pinpointing that mechanism could unlock additional therapeutic strategies.

Ultimately, the goal is to develop a non-opioid pain therapy that works by restoring natural cell function instead of masking symptoms. Given the widespread prevalence of chronic pain and the ongoing opioid crisis, this line of research has significant implications for public health and long-term pain management.

Research Paper

Trans-synaptic signaling through GRID1/glutamate receptor delta-1 and CBLN1/cerebellin-1 facilitates autophagic flux in central amygdala and prevents chronic pain

https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2025.2574968