Collaborating Minds Process Information in Remarkably Similar Ways During Shared Tasks

A new study from researchers at Western Sydney University offers a fascinating look into how our brains behave when we work together. The team found that when two people collaborate on a task—especially one where they must follow rules they created together—their brains begin to process information in strikingly similar ways. This goes beyond merely looking at the same thing; it reflects a deeper neural alignment that strengthens as cooperation continues.

The research, published in PLOS Biology, set out to understand how people’s cognitive processes synchronize during a shared activity. Humans collaborate constantly—whether farming, building, solving problems, or raising families—and successful cooperation requires shared rules and a shared understanding of the world. The researchers wanted to know: Do our brains actually begin to “think alike” when we work together?

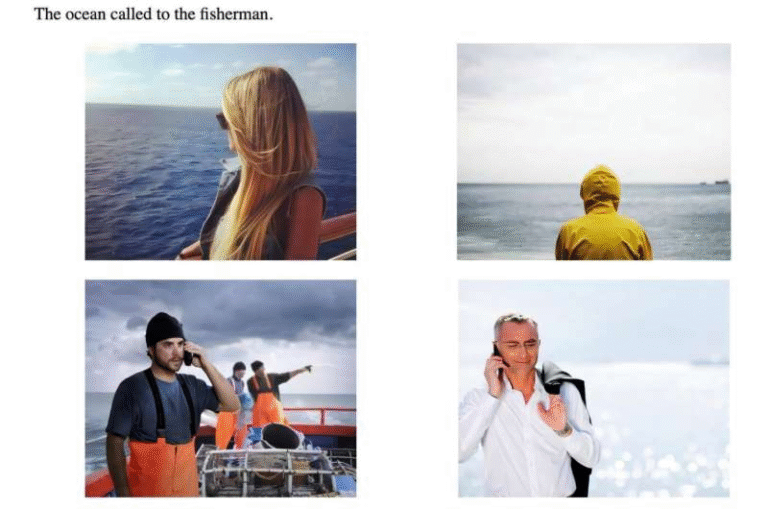

To find out, they examined how pairs of individuals processed information during a categorization task. They gathered data from 24 pairs, who each faced a sequence of patterned shapes and had to decide together how to categorize them. Before starting the task, each pair agreed on the specific rules they would use. These rules could involve sorting by wavy vs. straight lines, thick vs. thin lines, strong vs. weak contrast, or general shape features.

Once the rules were set, the pairs sat back-to-back, meaning they had no visual contact or nonverbal cues. This setup made sure that any alignment in their brain activity would emerge from shared mental processing, not from observing each other.

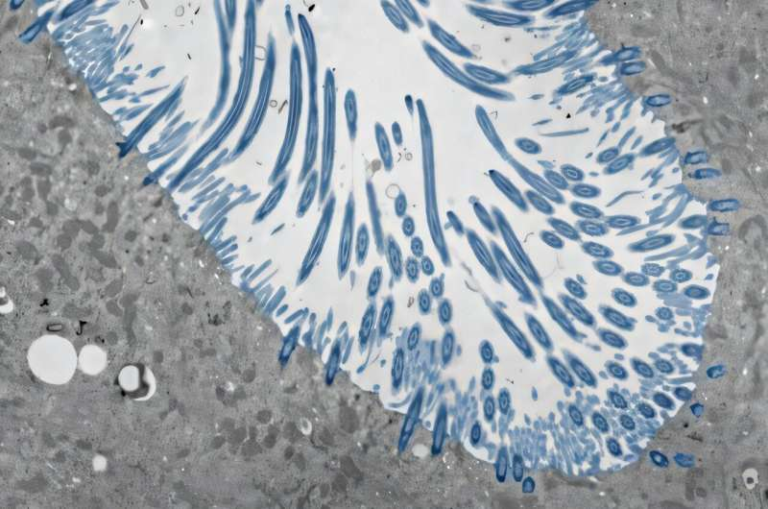

Both participants in each pair viewed the same shapes at the same time. While they categorized the stimuli, researchers used electroencephalograms (EEGs) to record their brain activity in real time. The scientists then analyzed the patterns to see how closely the two brains matched moment by moment.

The findings revealed a clear two-stage process. First, in the initial 45–180 milliseconds after each shape appeared, the brain activity of all participants—across all pairs—looked very similar. This early similarity was expected, since everyone was reacting to the same visual stimulus. It represented a shared sensory response.

But after about 200 milliseconds, something much more interesting happened. At this later stage, where cognition and rule-based decisions occur, similarities appeared only in the pairs who were collaborating. Randomly paired non-collaborating individuals, who acted as controls, didn’t show this alignment despite viewing the same stimuli.

Even more compelling, the similarity in brain activity between real pairs increased over time. As the task went on, the collaborating partners became more and more aligned in how they represented information internally. Their brains were effectively learning to reflect the rules they created together in a shared neural language.

This suggests that collaboration doesn’t only coordinate behavior—it shapes cognition itself. The longer people work together under mutually agreed-upon rules, the more closely their brains align in how they interpret and process information.

The authors point out that this alignment may play a crucial role in how humans develop traditions, social norms, and collective decision-making. When people repeatedly engage in shared tasks or rituals, their neural representations of the world may begin to converge. This could help explain why groups often develop common interpretations, expectations, and coordinated ways of acting.

While the experiment used an artificial setup—simple shapes, no verbal communication, and controlled conditions—the implications are broad. It opens the door to studying larger groups, real-world decision-making, and more complex collaborative environments. The fact that brain alignment can be measured using EEGs also makes the method accessible for future research.

To expand the context for readers, it is helpful to understand how this fits into the growing field of social neuroscience. Researchers have long suspected that humans synchronize not just emotionally but biologically when they interact. Previous studies have shown that people can exhibit neural synchrony, where their brain rhythms and timing patterns correlate during shared experiences like music, storytelling, or conversation.

However, this new study goes further. Instead of measuring broad synchrony, the researchers analyzed the specific patterns of information representation in the brain—a method known as representational similarity analysis. This allowed them to see how the content of cognition, not just its timing, aligned between two people. This is a far more precise way to investigate whether two minds are actually processing the same idea in the same way.

The fact that the alignment only appeared after rapid sensory processing—and strengthened as the pair improved at their joint task—strongly supports the conclusion that collaboration actively shapes cognitive processing.

Looking at the broader picture, understanding interbrain alignment may eventually provide insights into how teams function in workplaces, how teachers and students synchronize during learning, or how people build shared meaning in social groups. It may also shed light on why humans are uniquely capable of building cumulative cultures, where knowledge is passed down and refined across generations.

Of course, the authors point out limitations. The sample size was modest, and the experiment used simplified tasks that do not reflect the full richness of natural human interaction. The back-to-back design removed communication cues that normally support collaboration. Future studies may explore how alignment functions in more complex, dynamic environments.

Still, the results offer a compelling foundation for future work. They highlight the possibility that thinking together is not just a metaphor—humans may literally develop shared neural representations when they collaborate closely. And as the authors suggest, this could help explain how groups form traditions and make joint decisions over time.

This study adds an important piece to our understanding of cooperation, showing that the process may run far deeper than coordinated action. When people collaborate, their brains gradually begin to represent the world in similar ways, suggesting that cognition itself can become a shared space.

Research Paper Link: https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3003479