Early Childhood Adversity Can Rewire Brain Networks and Shape Lifelong Health Risks

Scientists have long known that difficult experiences early in life can leave lasting marks on physical and mental health. Children who grow up facing neglect, abuse, or chronic stress are more likely to struggle later with conditions such as anxiety, depression, addiction, and cardiovascular disease. What has been far less clear is exactly how the brain changes after early adversity in ways that persist into adulthood.

A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) offers one of the most detailed answers so far. Researchers from the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, working with collaborators from the University of Southern California, show that early life adversity can disrupt multiple interconnected brain networks, leaving the brain in a heightened state of threat sensitivity long after the original stress has passed.

How Early Life Adversity Was Modeled in the Study

Because it is not possible to conduct whole-brain, invasive neural activity studies across development in humans, the researchers turned to a well-established mouse model of early life adversity.

In this study, early adversity was introduced during infancy by limiting the amount of nesting material available to mother mice while they were caring for their pups. This lack of nesting material caused the mothers to display anxious and fragmented caregiving behavior, interfering with consistent nurturing. Importantly, this model does not involve direct physical harm to the pups. Instead, it mimics conditions similar to neglect, environmental instability, and chronic stress, which are common forms of adversity in human childhoods.

A separate group of mice was raised under normal conditions, with adequate nesting materials and typical maternal care. These two groups formed the basis for all later comparisons.

Testing the Brain’s Response to Threat in Adulthood

Once the mice reached adulthood, the researchers exposed them to a predator-related threat. The stimulus was the odor of fox urine, a scent that reliably triggers fear responses in rodents. As expected, both normally raised mice and mice that had experienced early adversity reacted with fear-related behaviors.

The crucial difference emerged when researchers looked inside the brain.

To capture brain-wide neural activity, all mice were injected with manganese, a metal that is absorbed by active neurons. The animals then underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans under sedation. Areas with higher neural activity accumulated more manganese, allowing researchers to see which brain regions were most active during and after the threat.

This technique, known as manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI), is particularly powerful because it allows scientists to observe activity across the entire brain, rather than focusing on just one or two regions at a time.

Hyper-Activation of Fear and Stress Networks

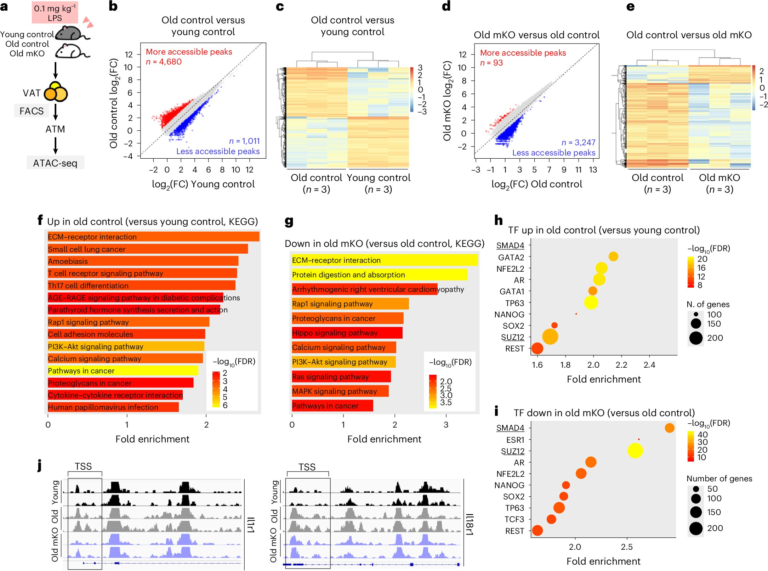

The brain scans revealed striking differences between the two groups of mice. Animals that experienced early life adversity showed exaggerated activation in several brain regions associated with fear and stress processing when exposed to the predator odor.

Key regions included:

- The amygdala, which plays a central role in fear detection and emotional processing

- The locus coeruleus, a brainstem region involved in arousal and the stress response

- Additional regions that regulate stress-related neurotransmitters such as dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin

Rather than being limited to one isolated circuit, the changes were seen across multiple interacting brain systems. This suggests that early adversity does not simply “turn up” fear responses in a single location but instead reconfigures how large-scale brain networks communicate during threatening situations.

Long-Lasting Effects That Persist After the Threat

One of the most important findings came not immediately after the threat, but nine days later. At that point, the normally raised mice showed a return toward baseline brain activity. In contrast, mice that experienced early adversity continued to show elevated neural activity in several regions.

Persistently active areas included:

- The locus coeruleus

- The posterior amygdala

- The hippocampus, which is involved in memory and emotional regulation

- Multiple parts of the hypothalamus, a key regulator of stress hormones and bodily responses

This sustained activation suggests that early adversity leaves the brain in a prolonged state of alertness, even long after an acute threat has ended. Such a pattern mirrors what is often observed in humans with chronic anxiety or post-traumatic stress, where the brain remains highly reactive to potential dangers.

Why These Findings Matter for Human Health

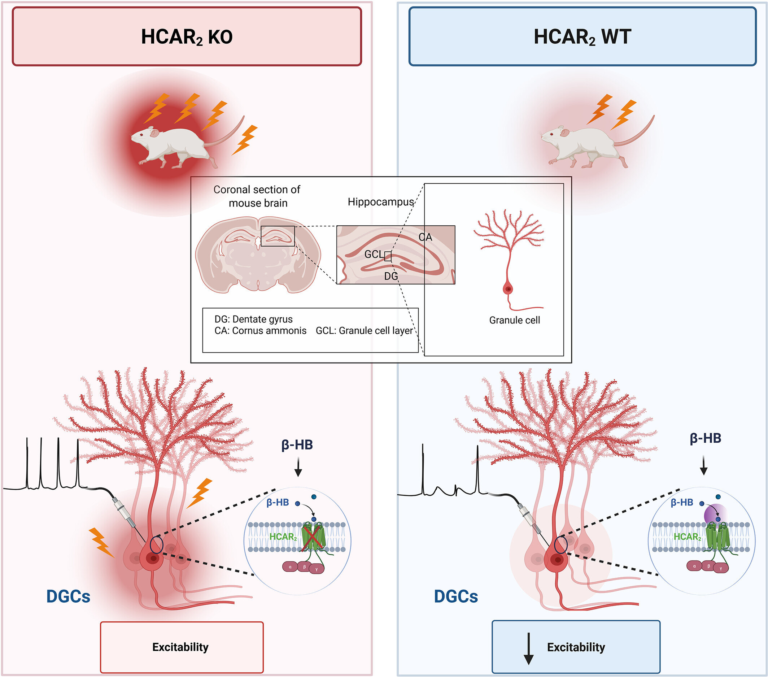

Although mouse brains differ from human brains in size and complexity, many of the regions affected in this study belong to what scientists often call the evolutionarily conserved core of the brain. Structures like the amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and brainstem stress centers are remarkably similar across mammals.

This means the findings offer important clues about human vulnerability to mental health disorders. The study suggests that early adversity may alter brain networks during sensitive developmental windows, creating long-term imbalances that affect how threats are processed later in life.

In humans, this could help explain why people exposed to childhood adversity are more likely to experience hypervigilance, heightened stress reactivity, mood disorders, and difficulty regulating emotions decades later.

Sensitive Periods in Brain Development

Another implication of the research is the idea of critical or sensitive periods in brain development. During these windows, the brain is especially plastic and responsive to environmental input. Stressful experiences during such periods may have outsized and lasting effects, compared with similar experiences later in life.

If researchers can identify comparable sensitive periods in humans, it could open the door to early screening tools that identify individuals at higher risk for stress-related disorders. This, in turn, could guide preventive interventions before mental health problems become entrenched.

Potential Paths Toward Treatment and Prevention

Understanding which brain regions and networks are most affected by early adversity also has implications for treatment. If specific stress-sensitive circuits are known to be overactive, future therapies might aim to target and normalize these networks.

Possible approaches could include:

- Behavioral interventions during early development

- Pharmacological treatments that regulate stress neurotransmitters

- Neuromodulation strategies designed to rebalance overactive circuits

The long-term goal is not simply to reduce symptoms after disorders develop, but to build resilience so that exposure to future stress does not automatically lead to anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Broader Context of Childhood Adversity Research

This study fits into a growing body of research showing that early life conditions shape the brain in deep and lasting ways. Previous human studies have linked childhood adversity to changes in brain connectivity, stress hormone regulation, immune function, and cardiovascular health. What makes this research stand out is its ability to show, at a whole-brain level, how adversity alters network-level brain dynamics over time.

Rather than focusing on isolated brain regions, the findings emphasize that mental health vulnerabilities emerge from imbalances across interacting systems, highlighting the complexity of how early experiences become biologically embedded.

Final Thoughts

The new findings provide compelling evidence that early childhood adversity can fundamentally reshape how the brain responds to threat, creating patterns of neural activity that persist into adulthood. By mapping these changes across the entire brain, the research brings scientists closer to understanding the biological roots of long-term mental health risk and points toward more informed strategies for prevention and intervention.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2506140122