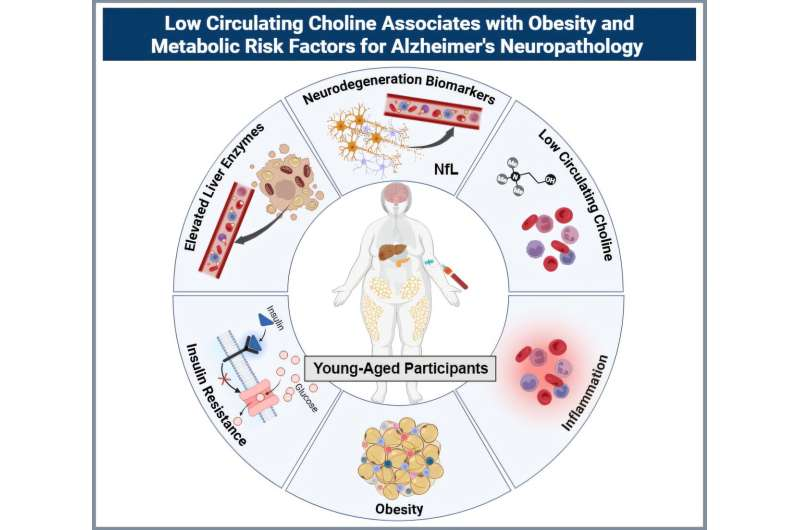

Early Obesity and Low Choline Levels May Set the Stage for Brain Inflammation and Memory Problems Later in Life

A new study from Arizona State University is drawing attention to a worrying pattern seen in young adults: those with obesity are already showing biological signs that resemble early stages of neurodegeneration, decades before any cognitive symptoms would normally appear. The research shines a spotlight on metabolic stress, inflammation, and notably low levels of the essential nutrient choline, suggesting that the roots of memory decline may begin far earlier than expected.

The study involved 30 adults in their 20s and 30s—half with obesity and half of normal weight. Each participant provided fasting blood samples that were used to measure circulating choline, inflammatory cytokines, insulin and glucose levels, liver-function enzymes, and levels of neurofilament light chain (NfL), a protein released when neurons are damaged. The results showed a clear divide: individuals with obesity had lower choline, higher inflammation, increased liver stress, stronger signs of insulin resistance, and elevated NfL, indicating early neuronal injury.

What made the findings even more striking was that the researchers compared this young adult data with biomarker patterns from older adults diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s disease. Across both groups, the same relationship appeared: low choline paired with high NfL. This similarity suggests that the biological pathways linked to long-term memory decline and neurodegenerative diseases may start decades earlier than typically assumed.

Researchers emphasized that the findings illustrate an interconnected pathway: metabolic dysfunction and chronic inflammation may influence neuronal health, and low choline could worsen this vulnerability. While obesity is already known to increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, this study adds growing evidence that obesity-related metabolic stress also affects the brain much earlier in adulthood.

A particularly important detail is the role of choline, an essential nutrient required for healthy liver function, cell-membrane structure, inflammation control, and the production of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is crucial for memory. The body produces only a small amount of choline, so dietary intake is the primary source. Foods rich in choline include eggs, fish, poultry, beans, and cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cauliflower. Despite this, national nutrition surveys consistently show that many Americans—especially adolescents and young adults—fail to meet recommended daily choline intake. The study also observed that young women had even lower choline levels than men, which is notable given that women experience disproportionately higher rates of cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s disease.

Another point raised by the researchers involves the rising use of GLP-1 weight-loss medications, such as semaglutide. These drugs are effective for weight reduction because they significantly decrease appetite, but this also means individuals may unintentionally consume fewer essential nutrients, including choline. The authors suggest that people using these medications may need to pay extra attention to choline intake or consider supplementation. More research is necessary to evaluate whether combining GLP-1 therapies with appropriate nutritional support can help maintain long-term metabolic and neurological health.

Although the study does not prove that low choline causes brain damage, it identifies a group of biomarkers—reduced choline, elevated inflammation, higher insulin resistance, liver stress, and increased NfL—that form a pattern also seen in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. This pattern in young adults is concerning, especially because cognitive symptoms generally do not appear until many years later. The results support earlier research in rodents showing that choline deficiency led to metabolic dysfunction, obesity-like changes, and increased Alzheimer’s-related pathology.

Below are additional sections that expand on the topic, offering useful background for readers who want a deeper understanding.

What Is Choline and Why It Matters

Choline is classified as an essential nutrient because the body cannot produce enough of it on its own. It plays a role in:

• Liver fat metabolism, helping prevent conditions such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

• Cell-membrane integrity, as part of phospholipids like phosphatidylcholine.

• Neurotransmitter synthesis, particularly acetylcholine, which affects memory, muscle control, and mood.

• Methylation reactions, which influence DNA expression, detoxification pathways, and brain development.

Low choline intake has been linked to liver injury, poor metabolic health, and in some studies, impaired cognitive performance. Pregnant individuals, for example, require more choline because it is vital for fetal brain development.

Understanding Neurofilament Light Chain (NfL)

NfL is a structural protein found inside neurons. When neurons experience stress or damage, NfL leaks into the bloodstream. Because of this, NfL is increasingly used as a biomarker of neurodegeneration. High NfL levels are commonly seen in:

• Alzheimer’s disease

• Mild cognitive impairment

• Multiple sclerosis

• Traumatic brain injury

The detection of elevated NfL in otherwise healthy, young adults with obesity suggests early brain vulnerability long before noticeable cognitive problems appear.

How Obesity Affects the Brain

Obesity is more than excess body fat. It is a condition marked by chronic low-grade inflammation, impaired insulin signaling, and metabolic stress. These issues contribute to:

• Reduced blood-brain barrier integrity

• Increased inflammatory cytokine activity

• Impaired neuronal energy metabolism

• Greater oxidative stress

Over time, these factors may accelerate cognitive aging and increase the risk of disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. The new findings imply that these processes begin earlier than scientists previously believed.

What This Means for Long-Term Brain Health

The study’s authors highlight the importance of maintaining healthy metabolic function and ensuring sufficient nutrient intake early in adulthood. While the research does not confirm that improving choline levels prevents cognitive decline, the consistency of the biomarker pattern suggests that diet and metabolic health may meaningfully influence brain health throughout life.

They also emphasize the need for larger, long-term studies to determine how these early biomarkers evolve over time and whether nutritional or lifestyle interventions—such as weight management, choline supplementation, or anti-inflammatory strategies—can decrease future neurodegenerative risk.

Overall, the findings point toward a proactive approach: supporting metabolism and nutrient status early may help build a foundation for healthier aging and reduced cognitive decline later in life.