Engineered Immune Cells Show Powerful Ability to Destroy Glioblastoma in Preclinical Models

Glioblastoma remains one of the most formidable and deadly brain cancers known today, with a five-year survival rate of less than 5%. Traditional treatments—surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and even modern immunotherapies—have consistently fallen short. The primary challenge is that glioblastoma creates a highly resistant environment with very few natural T cells, the immune system’s main cancer-fighting soldiers. Without these cells, the body has little chance of mounting a meaningful immune attack.

A new study from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and Geneva University Hospital (HUG) introduces an approach that tackles this long-standing problem directly: creating engineered CAR-T cells specifically designed to target components of the glioblastoma tumor environment itself. These customized immune cells succeeded in destroying tumor cells in animal models and may soon move toward human clinical trials.

What Makes Glioblastoma So Difficult to Treat

Glioblastoma forms a tumor mass composed not only of cancerous cells but also a complex network of support cells and structural proteins. Unlike cancers such as melanoma or certain lung cancers, glioblastoma contains very few natural T cells, which explains why standard immunotherapies fail. These treatments depend on stimulating T cells that simply aren’t present.

CAR-T cell therapy offers a workaround. Doctors collect T cells from a patient, genetically modify them in the lab so they can recognize a specific cancer target, and then infuse them back into the body. These engineered cells are designed to hunt down cancer. But for glioblastoma, choosing a safe, effective target has been the biggest obstacle.

Glioblastoma tumors are highly heterogeneous—different cells express different markers. A single target almost guarantees relapse because surviving cells quickly take over. In a previous study, the Geneva team identified PTPRZ1, a promising marker on certain tumor cells, but it wasn’t enough on its own.

The latest breakthrough expands the strategy not by adding another cell-surface marker but by going after a protein found in the tumor environment: Tenascin-C (TNC).

Targeting Tenascin-C: A Different Way to Attack the Tumor

Tenascin-C is a protein that forms part of the extracellular matrix, essentially the structural “jelly” surrounding tumor cells. In glioblastoma, this protein is produced in large quantities and released into the tumor environment.

Researchers engineered a new line of CAR-T cells that can recognize TNC and target the cells producing it. This approach has several advantages:

- It attacks cells contributing to the tumor structure, not just tumor cells themselves.

- It triggers pro-inflammatory reactions that lead to the destruction of TNC-producing cells.

- It produces a bystander effect, meaning the CAR-T cells can destroy nearby glioblastoma cells that do not produce TNC, widening the therapy’s reach.

- It avoids harming healthy cells, which typically do not produce Tenascin-C at these high levels.

This broader targeting mechanism is particularly important in glioblastoma, where no single marker exists across all cancer cells.

What the Animal Studies Showed

In mouse models designed to mimic human glioblastoma, the engineered CAR-T cells demonstrated several key abilities:

- They recognized and attacked TNC-rich areas of the tumor.

- They killed tumor cells producing Tenascin-C.

- They eliminated nearby tumor cells lacking TNC expression, amplifying the total impact.

- They produced no harmful reactions against healthy tissues.

- They prolonged survival significantly compared to untreated animals.

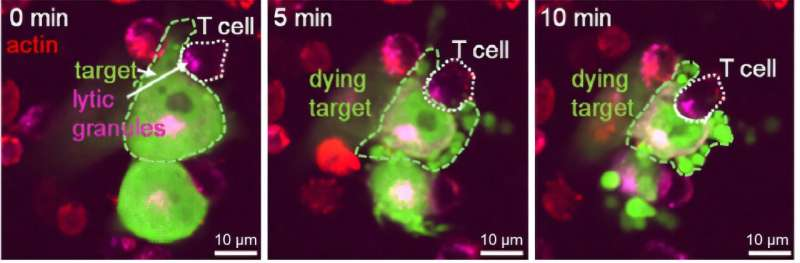

Real-time imaging even showed CAR-T cells making direct contact with glioblastoma cells and initiating destruction within minutes.

These results indicate that targeting the tumor environment—not only tumor cells—may be a highly effective strategy for solid cancers that have resisted other forms of immunotherapy.

Addressing CAR-T Cell Exhaustion

One of the biggest barriers to successful CAR-T therapy in solid tumors is immune cell exhaustion. As CAR-T cells encounter resistance within the tumor microenvironment, their activity drops quickly.

The Geneva team identified three markers associated with exhaustion and developed ways to counteract them. By doing this, they were able to maintain the CAR-T cells’ activity for much longer in mice. This improvement directly contributed to better tumor control and longer survival.

Preparing for Human Clinical Trials

With strong preclinical results, researchers are preparing for a clinical trial expected to begin in about a year in Geneva and Lausanne. Their long-term goal is to create CAR-T therapies that target multiple proteins simultaneously, reducing the chance of tumor escape due to heterogeneity.

Because every patient’s tumor is unique, the team also plans to adapt CAR-T cells individually to each case. This personalized approach aims to eliminate as many cancer cells as possible, even in tumors with diverse cellular populations.

If successful in humans, this could mark one of the most significant steps forward in glioblastoma treatment in decades.

Additional Context: How CAR-T Therapy Works

For readers curious about the broader science, CAR-T therapy follows a few essential steps:

- Collection: Doctors extract T cells from the patient’s blood.

- Engineering: Using viral vectors or gene-editing technologies, the cells are programmed to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that recognizes a protein on cancer cells.

- Expansion: The engineered T cells are multiplied in the lab.

- Infusion: Patients receive chemotherapy to create space for the new cells, followed by infusion of the CAR-T cells.

- Attack Phase: The CAR-T cells locate their target and kill cancer cells.

CAR-T therapy has revolutionized treatment for some blood cancers, but solid tumors like glioblastoma remain far more challenging due to their physical structure, immune-suppressing environment, and lack of consistent targets. This is why Tenascin-C, located in the extracellular matrix instead of on tumor surfaces, represents a promising new direction.

Why Targeting the Tumor Environment Matters

A tumor is more than a cluster of malignant cells. It includes:

- Structural proteins

- Blood vessels

- Immune cells

- Signaling molecules

- Support cells that help cancer grow

By targeting the environment instead of individual cancer cell markers, therapies may become less vulnerable to tumor evolution and relapse. Glioblastoma, with its extreme genetic diversity, stands to benefit greatly from this shift in strategy.

Looking Ahead

This study opens up possibilities beyond glioblastoma. Many solid tumors produce abnormal extracellular matrix proteins. If CAR-T cells can be trained to target these shared components safely, the approach might extend to other cancers long considered resistant to immunotherapy.

For now, the results in animal models are highly encouraging. The next step—human trials—will determine whether this innovative therapy can finally offer meaningful progress against a cancer that has seen far too little.

Research Reference

Targeting the extracellular matrix with Tenascin-C-specific CAR T cells extends survival in preclinical models of glioblastoma

https://jitc.bmj.com/content/13/11/e011382