Enzyme Replacement Therapy Brings New Hope for People Living With Ultra-Rare Hunter Syndrome

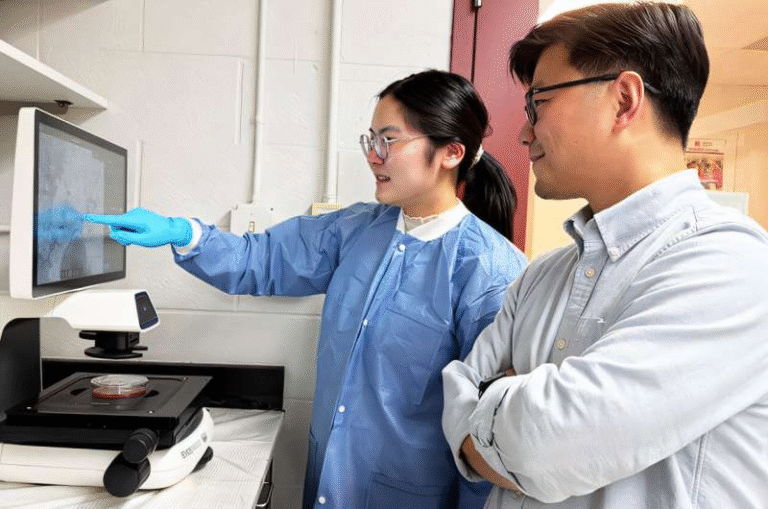

Ongoing clinical research at the University of North Carolina (UNC) is pointing toward what could become a first-of-its-kind enzyme replacement therapy for Hunter syndrome, an ultra-rare genetic disorder that causes severe physical and neurological decline. The findings, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggest that this experimental therapy may finally address one of the biggest unmet challenges in treating the disease: damage to the brain.

Hunter syndrome, formally known as Mucopolysaccharidosis II (MPS II), is a rare inherited condition that primarily affects boys. People with this disorder are unable to produce a critical enzyme needed to break down complex sugar molecules inside cells. Over time, these sugars accumulate throughout the body and brain, leading to progressive multisystem disease, cognitive impairment, and early death, often during adolescence.

For years, available treatments have helped manage some physical symptoms but have failed to protect the brain. The new therapy being studied at UNC could change that.

Why Hunter Syndrome Is So Difficult to Treat

MPS II is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme iduronate-2-sulfatase, which normally helps break down glycosaminoglycans such as heparan sulfate. Without this enzyme, waste products build up inside cells, damaging organs including the heart, lungs, joints, and most critically, the brain.

Standard enzyme replacement therapies already exist for Hunter syndrome. However, these treatments are limited because they cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, a protective membrane that prevents many substances in the bloodstream from entering the brain. As a result, while physical symptoms may improve, neurological decline continues unchecked.

This ongoing cognitive deterioration leads to the loss of speech, hearing, mobility, and ultimately, independence. Families often describe the disease as watching their loved one gradually lose skills they once had.

A Therapy Designed to Reach the Brain

The new research focuses on an experimental intravenous therapy called tividenofusp alfa, developed by Denali Therapeutics. What sets this drug apart is its ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, something no previous enzyme replacement therapy for Hunter syndrome has successfully done.

The therapy uses Denali’s proprietary TransportVehicle platform, which takes advantage of the body’s natural transport receptors to deliver the missing enzyme directly into the brain. Once there, the enzyme can begin breaking down accumulated heparan sulfate, targeting the root cause of neurological damage in severe MPS II.

The clinical trial was led by Dr. Joseph Muenzer, Director of the Muenzer MPS Research and Treatment Center and Bryson Distinguished Professor in Pediatric Genetics at the UNC School of Medicine. Dr. Muenzer has spent decades studying MPS disorders and has been deeply involved in the development of treatments for Hunter syndrome.

What the Clinical Study Found

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, evaluated how well tividenofusp alfa worked in individuals with MPS II. Researchers focused on whether the drug could reduce heparan sulfate levels in the brain, a key marker of disease progression.

The results were promising. Patients receiving the therapy showed substantial reductions in heparan sulfate, indicating that the enzyme was not only reaching the brain but actively doing its job. This reduction is especially significant for individuals with the severe form of Hunter syndrome, who typically experience rapid neurological decline.

Importantly, the therapy was administered intravenously, making it compatible with existing treatment approaches while adding a crucial new capability: central nervous system delivery.

Why These Results Matter for Families

For families affected by Hunter syndrome, the neurological aspect of the disease is often the most devastating. Children may gradually lose the ability to speak, hear, walk, and interact with the world around them.

Kim Stephens, Executive Director of the Muenzer MPS Research and Treatment Center, knows this reality firsthand. Her son Cole has MPS II and lost the ability to speak several years ago. Families like hers have long hoped for a treatment that could slow or prevent neurological decline rather than simply managing physical symptoms.

The possibility of a therapy that protects brain function represents a major shift in what treatment could look like for future patients.

The Role of UNC and Long-Term Research

UNC has played a central role in advancing MPS II research. More than two decades ago, Dr. Muenzer developed the first mouse model for MPS II at UNC. This model became a critical tool for studying how the disease affects the brain and testing new therapies.

Denali Therapeutics used this UNC-developed mouse model to generate preclinical data showing that tividenofusp alfa could cross the blood–brain barrier and reduce heparan sulfate storage in brain tissue. Those early findings laid the groundwork for the current clinical trial.

The Muenzer MPS Research and Treatment Center itself is the culmination of years of effort. The center brings together patient care, advocacy, education, and cutting-edge research under one roof, creating a rare-disease program designed to support families while pushing science forward.

How This Therapy Differs From Existing Treatments

To understand why tividenofusp alfa is so important, it helps to compare it with current options:

- Existing enzyme replacement therapies treat systemic symptoms only

- They do not enter the brain

- Neurological decline continues even with treatment

In contrast, tividenofusp alfa is specifically engineered to address both systemic and neurological disease, potentially offering a more complete treatment approach.

If future studies confirm long-term benefits, this therapy could redefine the standard of care for Hunter syndrome.

Broader Implications for Rare Disease Research

Beyond Hunter syndrome, this research may have implications for other rare genetic and neurodegenerative disorders. Many conditions remain difficult to treat because therapies cannot reach the brain.

The success of Denali’s TransportVehicle platform suggests that similar approaches could be used to deliver other biologic drugs across the blood–brain barrier, opening new possibilities for treating diseases previously considered out of reach.

What Comes Next

While the results are encouraging, this therapy is still undergoing clinical evaluation. Larger and longer-term studies will be needed to confirm its safety, effectiveness, and real-world impact on cognitive outcomes.

Still, for a disease with limited options and devastating consequences, tividenofusp alfa represents a meaningful step forward. It offers renewed optimism to researchers, clinicians, and families who have waited decades for a therapy that truly addresses the full spectrum of Hunter syndrome.

Research paper:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2508681