Experimental Liver Cancer Vaccine Shows Strong Early Results for Young Patients

A new experimental vaccine developed for a rare pediatric and young-adult liver cancer has delivered surprisingly strong early results, offering a potential breakthrough for a disease that historically has had almost no effective treatment options. The Phase I clinical trial, led by researchers at Johns Hopkins University and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, tested a therapeutic vaccine designed specifically for fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC)—a rare liver cancer that affects about 500 people in the United States each year, mostly adolescents and young adults who otherwise have healthy livers.

This cancer is especially challenging because most patients do not have typical liver-disease risk factors like hepatitis or cirrhosis. Even more importantly, there are no FDA-approved standard therapies for FLC, and when the tumor cannot be surgically removed, the prognosis has historically been poor. Most patients in this trial had already undergone at least one chemotherapy regimen without success. That context makes the results from this early study especially striking.

A Vaccine Built Around a Unique Cancer Driver

One of the most unusual and defining features of FLC is that almost all tumors share the same genetic abnormality: a fusion of two proteins, DNAJB1 and PRKACA, which join together to form a single hybrid protein called DNAJB1-PRKACA. This fusion does not exist in healthy tissues, making it a perfect target for a specialized vaccine.

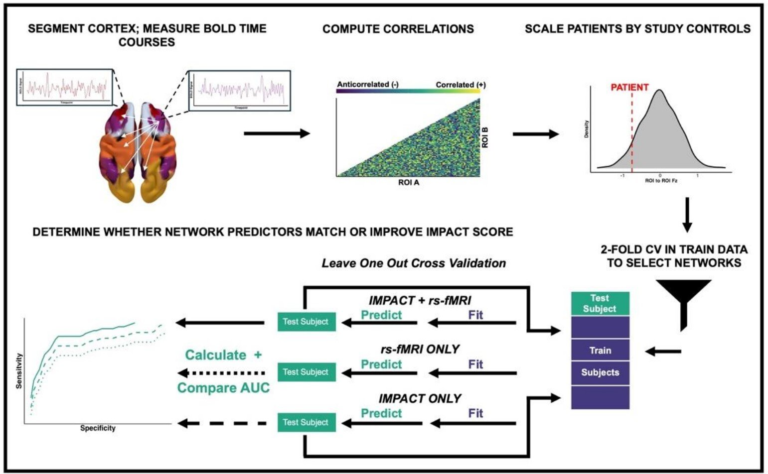

The experimental vaccine was designed as a therapeutic peptide vaccine—essentially a lab-made fragment that includes the exact amino-acid sequence where this abnormal fusion occurs. Because that fusion point is identical among patients, researchers were able to create a universal vaccine rather than customized versions for each person.

The vaccine was not tested alone. It was paired with immune checkpoint inhibitors—IV drugs commonly used in other cancers to help the immune system attack tumors more effectively. During the trial, patients received a combination of two such drugs along with the vaccine to jump-start a strong and sustained immune response.

How the Trial Worked

From April 2020 to September 2022, researchers enrolled 16 patients aged 12 or older, all with FLC that could not be surgically removed. The median age was 23, reflecting how young this cancer tends to strike. Four patients discontinued treatment early for various unrelated reasons, leaving 12 fully evaluable for both immune and clinical responses.

The treatment was given in two main stages:

- Priming phase (10 weeks):

Weekly vaccine injections for the first month, followed by injections once every three weeks. Alongside this, patients received two different checkpoint inhibitors every three weeks for four doses. - Maintenance phase (up to 2 years):

Vaccine injections every eight weeks for up to a year, plus continued monthly immune-therapy infusions.

This structure was designed to first train the immune system to recognize the fusion protein and then keep immune pressure on the tumor for as long as needed.

Clear Signs of Immune Activation and Tumor Control

The early results were highly encouraging. Out of 12 evaluable patients:

- 75% (9 patients) showed clear evidence of immune activation against the fusion protein or achieved disease control, meaning their cancer either stabilized or shrank.

- 25% (3 patients) experienced deep responses, with tumors shrinking so significantly that researchers now believe these patients may effectively be cancer-free.

- One of these major responders was a 13-year-old patient who achieved an almost complete response and continued immunotherapy for two years.

In another remarkable case, the combined treatment shrunk the tumor enough to allow surgical removal, something previously impossible. Before the vaccine, this patient had severe pain and was being considered for symptom-focused care rather than aggressive treatment. After beginning the trial, they experienced a meaningful tumor response within just a few months.

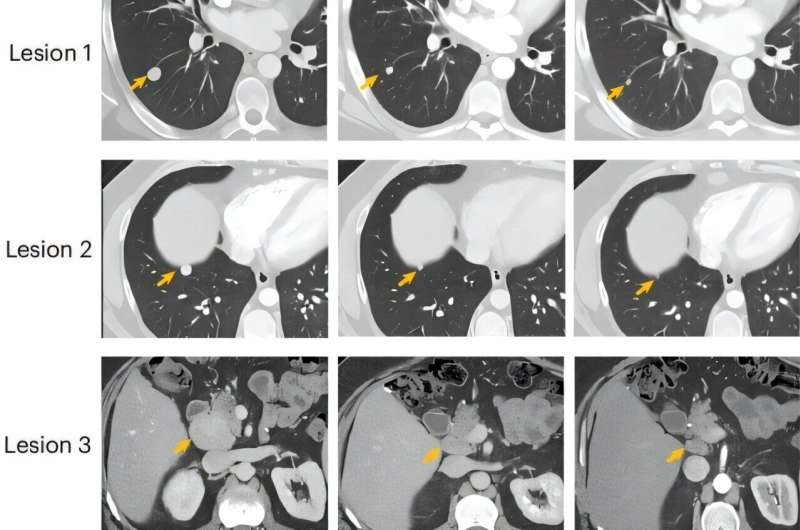

One patient, referred to as P12, achieved a 51% reduction in target lung lesions and abdominal lymph nodes—a partial response—before later developing new growth in a cardiophrenic lymph node, which required stopping the study therapy. This illustrates both the promise and the complexity of treating FLC.

Overall, the vaccine was well-tolerated. The most common issues were injection-site reactions, headaches, and fatigue. While some patients experienced more serious immune-related reactions, no life-threatening events were reported in this early trial.

Why This Matters for FLC Research

FLC research has historically been limited because of how rare the disease is. Many oncologists may only see one or two cases in their entire careers. Lack of widespread awareness and limited numbers of patients make clinical trials unusually difficult to run.

This vaccine, however, gives researchers something they have never had before:

A single, consistent molecular target shared by nearly every patient.

This consistency provides a path toward:

- Standardized treatment development

- More focused immunotherapy strategies

- Potential combination approaches like T-cell receptor therapies based on the same fusion target

The success of this Phase I trial demonstrates that cancers once considered “hard to target” or “undruggable” may become treatable through immune-training strategies.

What Comes Next

Because the early data show strong signs of safety and effectiveness, investigators are now expanding the study to include more patients and planning a larger clinical trial to evaluate long-term outcomes and broader applicability. This is a necessary step before the vaccine can be considered for wider use.

Researchers are also pursuing additional immunotherapy approaches based on this same fusion protein. These include exploring adoptive cell therapy, which involves collecting T cells from patients who responded to the vaccine, expanding or engineering them in the lab, and then using them as a personalized treatment for future FLC patients.

If larger trials confirm what this early study suggests, FLC patients—who currently have extremely limited treatment options—may soon have access to the first targeted therapy developed specifically for this disease.

Learning More About Fibrolamellar Carcinoma

For anyone interested in understanding the disease beyond this study, here are some key facts:

- FLC is distinct from typical hepatocellular carcinoma and usually occurs in younger individuals with no underlying liver disease.

- The disease often presents with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, weight loss, or fatigue, which sometimes delays diagnosis.

- Surgery remains the primary treatment when feasible, but tumors are frequently detected at a stage where removal is not possible.

- Chemotherapy and radiation generally offer limited benefit, underscoring the urgent need for targeted biological treatments.

- The DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion protein, discovered only within the last decade, has rapidly become the central focus of modern FLC research.

Understanding this fusion and developing therapies against it may ultimately improve survival rates and quality of life for young people facing this aggressive cancer.

Research Reference

Nature Medicine – A Therapeutic Peptide Vaccine for Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Phase 1 Trial

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-025-03995-y