Farm Life May Help Babies Build Stronger Immunity Against Food Allergies Earlier, New Study Suggests

Children raised on farms have long been known to develop fewer allergies than their urban counterparts, but scientists are still uncovering exactly why this happens. A new study from the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) offers compelling evidence that early farm exposure may help infants’ immune systems mature faster, particularly when it comes to protection against food allergies. The research highlights a crucial and often overlooked factor in early immune development: breast milk and maternal antibodies.

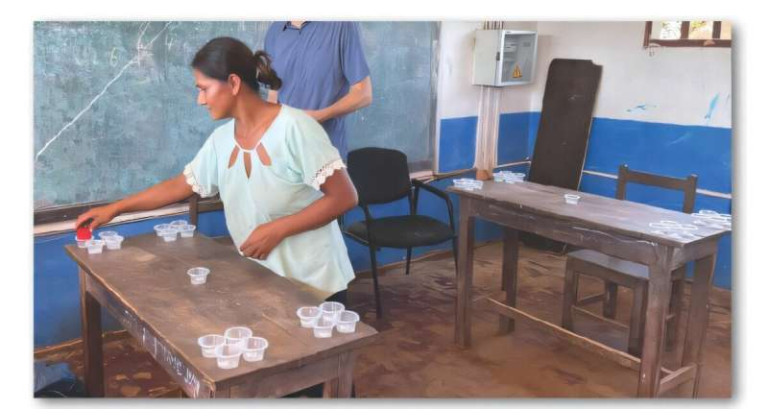

The study focused on families from Old Order Mennonite (OOM) farming communities in New York’s Finger Lakes region and compared them with urban and suburban families from Rochester. Researchers followed mothers and babies from pregnancy through the infants’ first year of life, collecting a wide range of biological samples, including cord blood, infant blood, stool, saliva, and human milk. This long-term approach allowed scientists to closely examine how early-life environments influence immune development over time.

Faster Immune Maturation in Farm-Exposed Babies

The central finding of the study is that infants growing up in farming environments show signs of earlier immune maturation. Specifically, these babies had a higher number of “experienced” B cells, the immune cells responsible for producing antibodies. Compared to urban infants, farm-exposed babies had immune systems that appeared to be more advanced during the very first year of life.

B cells play a vital role in how the body responds to food and environmental exposures. When these cells mature properly, they help the immune system recognize harmless substances—like food proteins—without overreacting. In farm-raised infants, researchers observed higher levels of memory B cells and IgG-positive B cells, both indicators of a more developed antibody-producing system.

Along with these cellular differences, farm-exposed infants had higher levels of protective antibodies, including IgG and IgA, in their blood, saliva, and stool. These antibodies are essential for immune tolerance and gut health, suggesting that farm life may give infants a stronger foundation for handling new foods and microbes safely.

The Role of Breast Milk in Allergy Protection

One of the most striking aspects of the research involves breast milk. The study found that mothers from Old Order Mennonite families had significantly higher levels of IgA antibodies in their milk. IgA plays a critical role in protecting the gut and shaping immune responses during infancy.

The researchers paid particular attention to egg-specific antibodies, since egg allergy is one of the most common food allergies in young children. Mennonite infants had higher levels of egg-specific IgG4 antibodies in their blood, while Mennonite mothers had higher levels of egg-specific IgA antibodies in their breast milk.

When researchers compared three groups—Mennonite families, Rochester families whose infants did not develop egg allergy, and Rochester families whose infants did—they found a clear pattern. The highest antibody levels were seen in Mennonite breast milk, the lowest in Rochester mothers whose infants developed egg allergy, and intermediate levels in Rochester mothers of non-allergic infants. This gradient strongly suggests a link between food-specific antibodies in breast milk and protection against food allergies.

While the study does not prove direct causation, the association is strong enough to raise important questions about how maternal immunity influences infant health.

Why Diet May Matter More Than We Thought

A key question is why Mennonite mothers have higher levels of food-specific antibodies in the first place. One likely explanation is dietary exposure. Old Order Mennonite families often raise their own chickens and consume eggs regularly. Repeated exposure to egg proteins appears to boost mothers’ antibody levels, which are then transferred to infants through both the bloodstream and breast milk.

This idea fits well with established immunology principles. Just as vaccines or infections can stimulate antibody production, frequent consumption of specific foods may help the immune system recognize those foods as harmless. In this way, maternal diet during pregnancy and breastfeeding could quietly “train” an infant’s immune system before the child ever eats those foods directly.

Immune Differences Begin Even Before Birth

The study also revealed immune differences that appear at birth, pointing to the role of prenatal exposure. Infants born into farming families had higher levels of IgG and IgG4 antibodies in cord blood against environmental allergens like dust mites and horse. In contrast, urban infants had higher antibodies against peanut and cat.

Researchers also detected food antigens and antigen-specific IgA in cord blood, suggesting that some immune education may begin in the womb. This finding adds to growing evidence that the maternal immune system and environment influence infant immunity long before birth.

The Broader “Farm Effect” on Immunity

While breast milk and maternal antibodies are central to this study, researchers emphasize that the protective “farm effect” is multifactorial. Old Order Mennonite families differ from urban families in many ways that can shape immune development. These include daily exposure to farm animals, higher contact with environmental microbes, use of well water, lower reliance on certain antibiotics, and longer or more frequent breastfeeding.

Previous research from the same cohort has also shown distinct gut microbiome patterns in farm-raised infants. A diverse and well-balanced microbiome is known to support immune regulation and reduce allergy risk, further reinforcing the idea that early environmental exposure plays a critical role.

What This Means for Allergy Prevention

The findings have already inspired the next phase of research. URMC is now leading a randomized clinical trial involving pregnant women and new mothers. Participants are assigned either to regularly consume egg and peanut during late pregnancy and early breastfeeding or to avoid them altogether. Researchers will track maternal antibody levels and monitor whether infants develop food allergies.

This work builds on existing evidence that early introduction of peanut and egg directly to infants can lower allergy risk. The new question is whether maternal diet during pregnancy and breastfeeding can provide an additional layer of protection through antibodies passed to the baby.

Understanding Food Allergies and Early Immunity

Food allergies occur when the immune system mistakenly identifies certain food proteins as dangerous. Antibodies like IgE drive allergic reactions, while antibodies such as IgG4 and IgA are associated with immune tolerance. The balance between these antibody types appears to be crucial in determining whether a child develops an allergy or learns to tolerate a food.

By showing higher levels of tolerance-associated antibodies in farm-raised infants, this study strengthens the idea that early immune education—shaped by environment, diet, and maternal immunity—can have lasting health effects.

Looking Ahead

While not every family can or should adopt a farming lifestyle, studies like this help identify specific, transferable factors that may reduce allergy risk. Understanding how maternal diet, breastfeeding, and early environmental exposures work together could eventually lead to practical guidelines that benefit families everywhere.

As researchers continue to explore these connections, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: the immune system’s relationship with food and the environment begins much earlier than previously believed, and sometimes, the simplest exposures may offer the strongest protection.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.ads1892