Fruit Fly Pigmentation Helps Scientists Discover Genes That Control Brain Dopamine and Sleep

Dopamine is one of those brain chemicals that seems to do a bit of everything. It plays a central role in movement, learning, motivation, mood, and sleep, and when dopamine signaling goes wrong, the effects can be serious. Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, addiction, and sleep disorders are all linked to disruptions in dopamine. While scientists have spent decades studying how dopamine works inside the brain, one big question has remained harder to answer: how does the body regulate dopamine levels in the first place?

A new study published in iScience in January 2026 takes an unexpected route toward answering that question—by looking at the body color of fruit flies.

Why fruit flies are surprisingly useful for dopamine research

The research was carried out by scientists at Baylor College of Medicine and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, led by Dr. Shinya Yamamoto. Their model organism of choice was Drosophila melanogaster, the common laboratory fruit fly, which has long been a favorite in genetics and neuroscience.

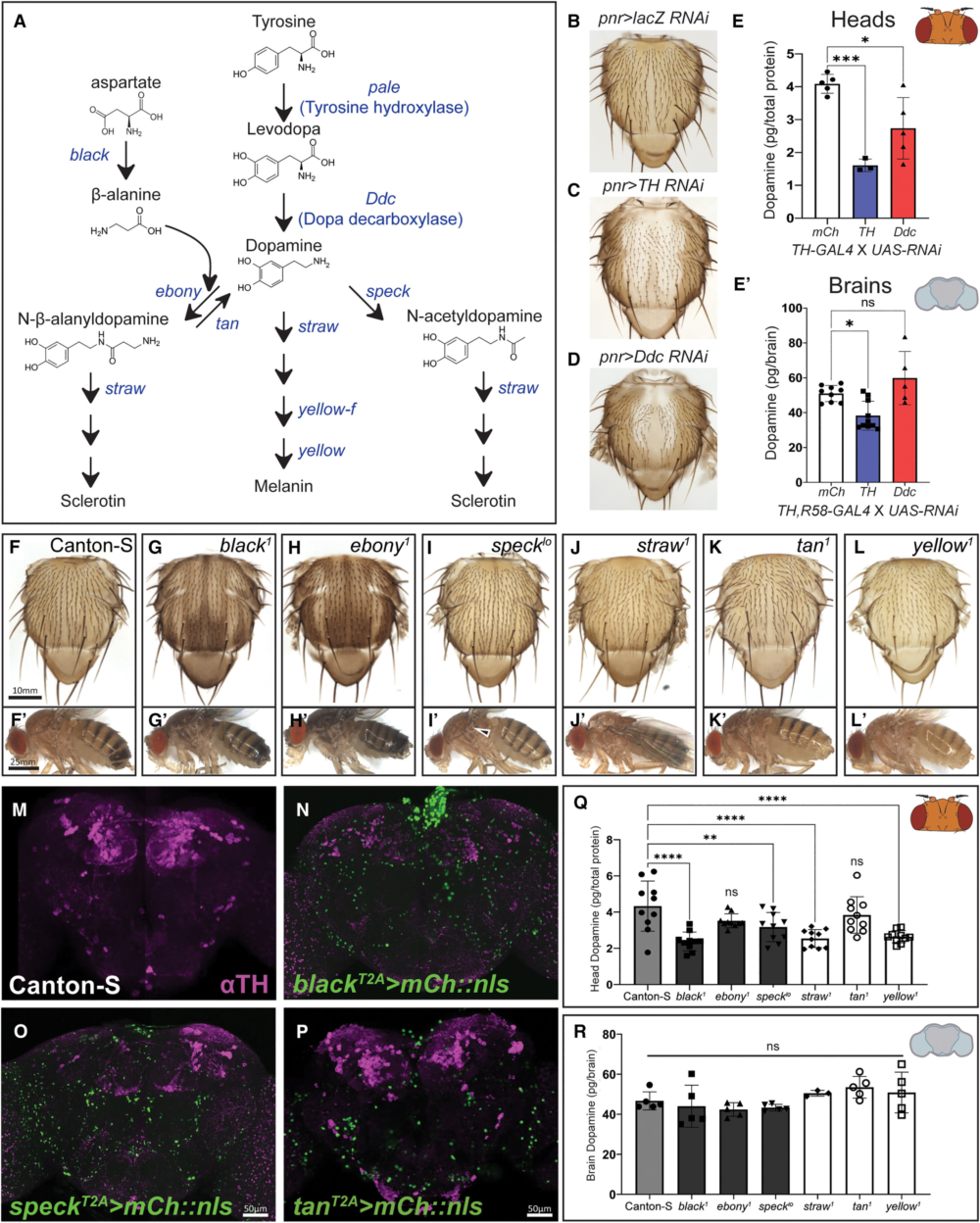

Fruit flies may seem far removed from humans, but they share a surprisingly large number of genes with us. Even more importantly, flies use dopamine in two very different ways. Just like humans, they rely on dopamine in the brain to regulate neural activity and behavior. But flies also use dopamine to produce melanin, the pigment that gives their outer shell, or cuticle, its color.

This dual role gave researchers a clever idea. If dopamine-related processes change, those changes might show up as visible differences in pigmentation. Instead of relying only on complex biochemical tests, scientists could literally look at the flies and spot clues.

A massive gene-silencing screen

To test this idea, the team used RNA interference (RNAi), a technique that allows researchers to selectively “silence” specific genes and observe what happens next. They started with more than 450 genes that previous research suggested might influence pigmentation in fruit flies.

By systematically silencing these genes, the researchers identified 153 genes that consistently altered the flies’ body color. This alone was a significant finding, but what made it even more interesting was how relevant these genes are to humans. About 85 percent of the pigmentation-related genes are conserved in people, and more than half have already been linked to neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism, epilepsy, and intellectual disability.

Pigmentation, it turns out, was pointing toward much deeper biology.

Connecting pigmentation genes to brain function

The next step was to find out whether these pigmentation genes also affected brain dopamine levels and behavior. To do this, the researchers silenced the genes specifically in dopamine-producing neurons and then measured changes in movement and sleep.

Out of the 153 pigmentation genes, 50 were associated with unusual locomotion or altered sleep patterns. This suggested that many genes initially identified through changes in body color also play important roles in the brain.

From this group, the scientists narrowed their focus to 35 genes that met several criteria: they were present in humans, caused strong pigmentation changes in flies, and produced noticeable behavioral effects.

When dopamine levels were directly measured, 11 of these genes significantly altered dopamine, most often by reducing it. Interestingly, the researchers found no simple or consistent relationship between body color and dopamine levels, showing that pigmentation is a helpful clue—but not a perfect stand-in—for what is happening in the brain.

Two standout genes: mask and clu

Among the most compelling discoveries were two genes called mask and clu. Silencing either gene led to a reduction in brain dopamine, but they did so in different ways and produced distinct behavioral effects.

The mask gene turned out to influence dopamine production quite directly. When mask was silenced, the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, the key enzyme required to synthesize dopamine, dropped significantly. As a result, dopamine levels in the brain decreased.

This biochemical change had clear behavioral consequences. Fruit flies normally show a behavior known as light anticipation, becoming more active just before dawn. Flies lacking functional mask lost this anticipation and instead slept more during that early-morning period.

To confirm that dopamine was responsible, researchers fed the flies L-DOPA, a precursor molecule that the brain converts into dopamine and that is commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease. The treatment restored normal sleep patterns, strongly linking the effects of mask silencing to dopamine deficiency. The same flies also showed a reduced response to caffeine, a stimulant whose wake-promoting effects depend on dopamine signaling.

The clu gene, on the other hand, told a different story. Silencing clu also increased sleep, but it did not disrupt light anticipation. Even more telling, L-DOPA did not reverse the effects, suggesting that clu influences sleep and dopamine through a more indirect or downstream mechanism.

What this means for human health

By starting with something as simple as fly pigmentation, the researchers uncovered previously unrecognized genetic regulators of dopamine. This approach opens the door to identifying new molecular pathways that help maintain dopamine balance in the brain.

Because many of the genes identified in this study are conserved in humans, the findings could eventually contribute to new strategies for treating neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, addiction, and various sleep disorders all involve disruptions in dopamine signaling, and understanding how dopamine levels are controlled may offer fresh therapeutic angles.

A closer look at dopamine’s role in sleep

Dopamine is often associated with reward and motivation, but its role in sleep is just as important. In both flies and humans, dopamine helps regulate wakefulness, circadian rhythms, and responsiveness to stimulants. Too little dopamine can lead to excessive sleepiness and disrupted daily rhythms, while too much can interfere with normal sleep.

This study reinforces the idea that sleep regulation depends not only on classic “sleep genes” but also on broader metabolic and signaling pathways, including those linked to pigmentation and cellular maintenance.

Why this research approach matters

One of the most interesting aspects of this work is the creative screening strategy. Instead of starting with behavior or brain chemistry alone, the researchers used a visible physical trait to guide their investigation. This kind of cross-system thinking highlights how interconnected biological processes really are.

It also shows why model organisms like fruit flies remain so valuable. Their short life cycles, genetic tractability, and shared biology with humans allow scientists to run large-scale experiments that would be impossible in more complex animals.

The road ahead

While this study focused on flies, it provides a roadmap for exploring similar mechanisms in mammals. Future research will be needed to determine exactly how genes like mask and clu function in the human brain and whether they could be targeted safely for therapeutic purposes.

For now, the findings serve as a reminder that sometimes, big insights into brain health can come from the smallest creatures—and even from something as seemingly simple as body color.

Research paper:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004225026495