Gentle Stem-Cell and Islet Transplant Cures Type 1 Diabetes in Mice and Resets the Immune System

A new study from Stanford Medicine has delivered one of the most intriguing breakthroughs in Type 1 diabetes research so far. Researchers successfully prevented and reversed autoimmune Type 1 diabetes in mice using a combination of blood stem-cell transplantation and pancreatic islet-cell transplantation from an immunologically mismatched donor. Even more impressive, the mice did not need insulin, immunosuppressive drugs, or any additional treatment for the entire six-month study period. Everything hinged on building what the researchers call a hybrid immune system—a blend of donor and recipient immune cells that peacefully coexist.

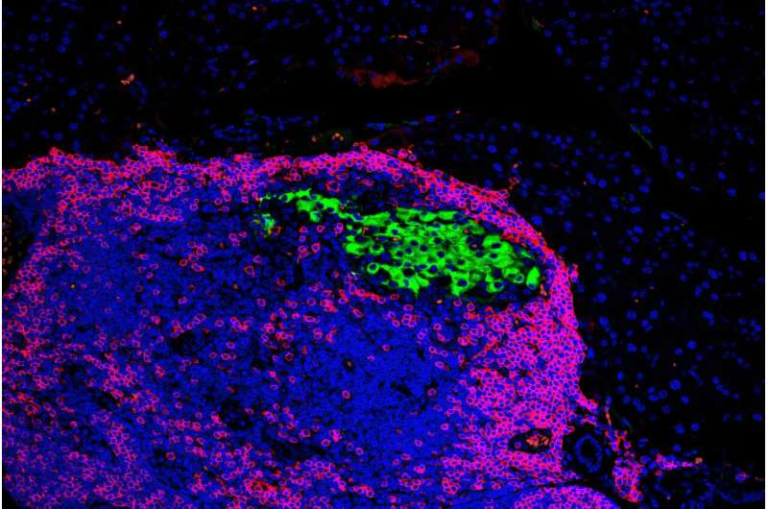

Credit: Journal of Clinical Investigation (2025)

Below is a clear, detailed breakdown of what the scientists did, why it matters, and what challenges remain before this can move toward human trials.

How the Researchers Successfully Eliminated Type 1 Diabetes in Mice

Type 1 diabetes develops when the immune system mistakenly destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. The Stanford team aimed to solve two problems at once:

- Replace the lost islet cells, and

- Reset the malfunctioning immune system so it stops attacking new cells.

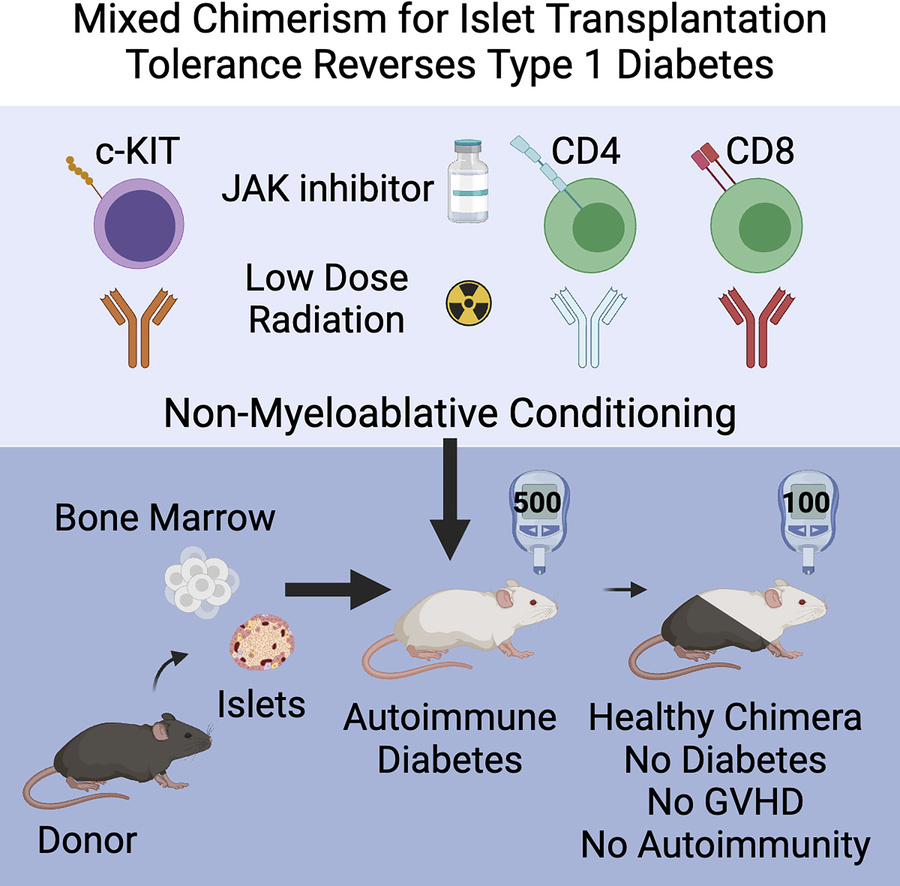

To accomplish this, they transplanted hematopoietic (blood) stem cells and islet cells from an unrelated donor into mice. Typically, mismatched donor tissue triggers aggressive immune rejection or, in worst cases, graft-versus-host disease, where the donor’s immune system attacks the host. Remarkably, neither occurred here.

The key was a carefully engineered gentle pre-transplant conditioning regimen. Previous bone marrow transplants required high-dose chemotherapy and radiation—dangerous and harsh enough that they would never be used for a non-life-threatening autoimmune disease. But Stanford researchers have gradually developed a safer method. In earlier work published in 2022, they created a reduced-intensity preparation using targeted antibodies and low-dose radiation.

This new study built on that foundation but had to tackle something even more difficult: curing autoimmune diabetes, not diabetes artificially induced by toxins. In autoimmune mice, the immune system spontaneously attacks beta cells, just as it does in humans with Type 1 diabetes. That means new islet cells face not just typical transplant rejection, but autoimmune destruction all over again.

To address this, the researchers added a drug used to treat autoimmune diseases onto their pre-transplant protocol. After this adjustment, the results were striking. In mice that had not yet developed diabetes but were genetically destined to, 19 out of 19 animals never developed the disease. In mice with long-standing autoimmune diabetes, 9 out of 9 were cured after receiving both blood stem cells and islet cells.

After transplantation, the mice formed a mixed immune system. Donor immune cells educated the host system to stop attacking islets altogether, while learning themselves not to attack host tissues. This balanced immune environment avoided graft-versus-host disease entirely.

All the mice maintained normal blood sugar levels without any external insulin or post-transplant immune suppression.

Why Creating a Hybrid Immune System Is Such a Big Deal

One of the greatest barriers to curing Type 1 diabetes is that the immune system continually seeks and destroys insulin-producing cells—even if they’re transplanted from a donor. That’s why islet transplantation in humans typically requires lifelong immunosuppressive therapy, which carries serious risks and often isn’t effective long-term.

By building a hybrid immune system, the Stanford researchers essentially reset immune tolerance. The host immune system no longer viewed islets as targets, and the donor immune cells did not attack host tissues.

This idea builds on decades of research by the late Dr. Samuel Strober and his colleagues, who explored mixed-immune-system approaches for kidney transplantation. Their work showed that if the immune system is carefully reshaped, a person can accept an organ transplant without lifelong immunosuppressive drugs. Some kidney recipients in earlier studies maintained healthy transplanted organs for decades using this principle.

What’s different now is that this team applied the same concept to an autoimmune disease, where the challenge isn’t just foreign tissue rejection but a self-destructive immune loop.

How the Team Created a Gentler Transplant Preparation

Traditional bone marrow transplants are often reserved for cancers such as leukemia because the required high-dose radiation and chemotherapy essentially wipe out the recipient’s entire immune system. This is too dangerous for diseases like Type 1 diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis.

The Stanford team designed a safer and more targeted approach:

- Antibodies that selectively target stem cells (including those against CD117)

- T cell–modulating antibodies to prevent severe immune reactions

- Low-dose radiation

- A drug commonly used for autoimmune disorders

These components together cleared just enough space in the bone marrow for donor stem cells to take root while avoiding life-threatening risk.

This approach allowed the donor and host cells to coexist without triggering widespread immune damage.

Remaining Challenges Before Human Trials Can Begin

Although the breakthrough is exciting, several real-world obstacles remain:

1. Human islet supply is limited.

Islets currently must come from deceased donors, and the yield is often small. A single human pancreas may not provide enough functional islets to reverse long-standing Type 1 diabetes in a patient.

2. Blood stem cells and islets must come from the same donor.

This requirement ensures immune matching during hybridization, but complicates donor availability.

3. Safety must be proven long-term.

Even though mice avoided graft-versus-host disease during the six-month experiment, humans would require far longer observation.

4. Conditioning methods must remain gentle enough for human use.

Targeted antibody-based regimens are promising, but risks must remain extremely low for a non-fatal condition like Type 1 diabetes.

Scientists are already exploring potential solutions. These include generating lab-grown islet cells from pluripotent stem cells, increasing islet survival after transplant, and further lowering the intensity of conditioning regimens.

What This Breakthrough Could Mean for Other Diseases

This approach may eventually help treat far more than Type 1 diabetes. Because it rebalances the entire immune system, it could one day be used for:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Lupus

- Sickle cell anemia

- Transplants of mismatched organs without chronic immunosuppression

By safely rebooting the immune system, this method has the potential to reshape how medicine approaches chronic autoimmune and transplant-related diseases.

A Quick Look at Type 1 Diabetes and Why It’s Hard to Cure

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the body destroys its own insulin-producing beta cells. Without insulin, the body can’t regulate blood sugar. Current treatments focus on managing the disease, not reversing it.

A true cure requires solving three separate problems:

- Replacing beta cells

- Stopping the autoimmune attack

- Preventing rejection of transplanted cells

This new hybrid-immune-system method is one of the first to tackle all three simultaneously.

Research Paper Link

Curing autoimmune diabetes in mice with islet and hematopoietic cell transplantation after CD117 antibody-based conditioning

https://www.jci.org/articles/view/190034