Head CT Scans in U.S. Emergency Rooms More Than Doubled in 15 Years, Raising Questions About Use and Access

A major new study published in 2025 offers an in-depth look at how dramatically the use of head CT scans has grown in emergency departments (EDs) across the United States—and why that trend matters. Between 2007 and 2022, the number of these scans more than doubled, climbing from 7.84 million to 15.98 million annually. In practical terms, this means that head CTs rose from being used in 6.7% of all emergency department visits to 10.3% of visits.

The researchers analyzed data from a large national hospital database designed to give population-level estimates. They focused on shifts in CT use over time and examined which patient groups were more or less likely to receive head CTs in emergency situations. What they found adds important nuance to ongoing conversations about imaging use, health-care equity, and emergency decision-making.

A key takeaway is that head CT scans remain a crucial tool for diagnosing urgent neurological conditions—things like possible strokes, internal bleeding, or severe head trauma. These are time-sensitive and high-risk situations where a scan can be the difference between the right treatment and a missed diagnosis. But the study also highlights a key tension: while some patients might not receive scans when they’re needed, others may be getting scans that add cost and radiation exposure without meaningful benefit.

One of the most striking patterns uncovered was a set of disparities in who receives CT scans. After researchers accounted for factors like age and the reason for the hospital visit, they found that Black patients were 10% less likely to receive a head CT compared to white patients. People insured through Medicaid were 18% less likely to get a scan compared to those with Medicare or private insurance. And patients treated in rural hospitals were 24% less likely to undergo a head CT than those seen at urban facilities. These gaps raise questions about access, clinician decision-making, resource availability, and systemic inequities within emergency care.

Age played a major role as well. Individuals 65 years and older were six times more likely to undergo a head CT than patients under 18. This difference makes sense clinically, since older adults face higher risks of stroke, falls, and other neurological emergencies. But this disproportion also highlights how much the aging population may be driving increased imaging use nationwide.

As with all studies, this one has limitations—most importantly, the dataset lacked information about a patient’s medical history, how long they had been experiencing symptoms, or how severe those symptoms were. Without that context, the study cannot determine whether an individual CT scan was medically necessary. The findings instead offer a snapshot of usage patterns rather than judgments about misuse.

Still, the larger trends are worth paying attention to. Increased CT use in the ED may reflect improvements in treatment protocols, particularly in time-sensitive areas like acute stroke care. Modern stroke interventions often require rapid imaging, sometimes multiple scans, and growing public awareness means more patients are seeking emergency care quickly. But expanded imaging also means higher cumulative radiation exposure, longer ED wait times, and higher costs for both patients and hospitals. Because CT scans are a limited resource, increased use may strain emergency departments already dealing with overcrowding and staffing shortages.

The study authors stress the importance of finding the right balance—avoiding underuse, which can lead to missed diagnoses, while also preventing overuse, which can burden patients and the health-care system. Their findings suggest that clinicians, policy makers, and hospital leaders need to continue evaluating when head CTs are truly necessary and how to provide equitable access to imaging for all patients.

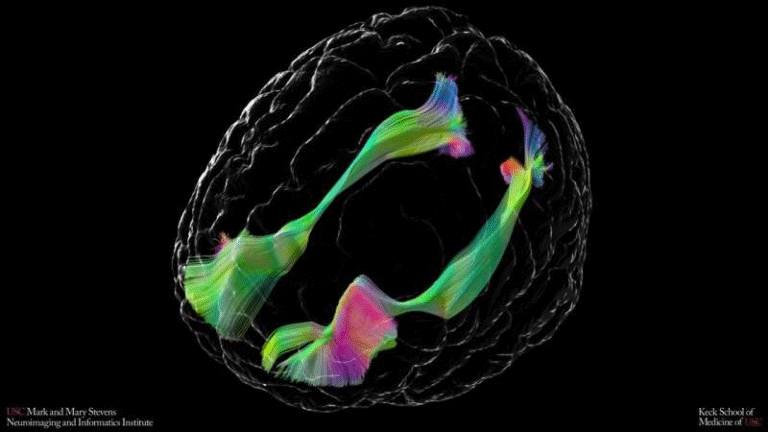

Beyond the news itself, it’s useful to understand the broader context around CT scans and why this study matters. A CT scan, or computed tomography scan, uses X-ray imaging technology paired with computer processing to create detailed images of internal structures. They are fast, widely available, and particularly effective for spotting bleeding in the brain, skull fractures, and other acute neurological changes. That’s why they’re often the first imaging test ordered in emergencies involving head pain, trauma, confusion, seizures, or sudden neurological deficits.

However, CT scans rely on ionizing radiation, which can increase cancer risk over a lifetime—especially when people undergo many scans or when children are exposed, since their developing tissues are more sensitive. While a single head CT carries a low risk, population-level radiation exposure becomes significant when millions of scans are performed each year. This is one reason many medical guidelines emphasize using CT imaging only when clearly needed.

Emergency departments are often under pressure to diagnose and treat quickly, and imaging offers clarity in uncertain situations. Over the last two decades, EDs in the U.S. have become increasingly reliant on diagnostic technology—CT, MRI, and ultrasound—in part because of concerns about missing serious conditions and in part because imaging has become faster and more accessible. But this growth has fueled ongoing debates about how to best use limited emergency resources while safeguarding patient well-being.

This is where clinical decision rules come into play. Tools like the Canadian CT Head Rule or the NEXUS criteria are designed to help clinicians determine which patients with head injuries truly need imaging. These evidence-based guidelines have been shown to reduce unnecessary scans without compromising patient safety. Still, adoption varies between hospitals, and many clinicians may err on the side of caution when assessing a patient with uncertain symptoms.

The disparities highlighted in the new study add another layer to the discussion. When certain groups—such as Black patients or Medicaid recipients—receive fewer scans even after controlling for clinical factors, it raises concerns that implicit biases, differences in access, or resource limitations could be influencing medical decisions. Meanwhile, lower imaging rates in rural hospitals may reflect limited staffing, older equipment, or slower access to radiology specialists. As policymakers work to close gaps in health-care equity, understanding how technology is distributed and used becomes essential.

On the other side of the spectrum, some patients may receive scans that were unlikely to help. For example, many people seen in the ED for mild headaches or dizziness do not benefit from imaging, according to clinical guidelines. Yet head CTs are still commonly ordered in these cases, partly because clinicians and patients alike often feel more reassured with imaging—even when the likelihood of uncovering a serious condition is low.

Overall, the findings of this study serve as a reminder that imaging is a powerful tool, but one that needs thoughtful use. Emergency medicine is fast-moving, complex, and burdened with high stakes. Balancing patient safety, efficiency, and fairness requires ongoing evaluation of how tools like CT scans are integrated into care.

As more data becomes available, future research may be able to examine CT scan appropriateness in greater detail, explore trends by region or hospital type, and assess how newer technologies—such as low-dose CT and AI-assisted diagnostic tools—might change the landscape of emergency imaging.

For now, one point is clear: understanding who gets imaged, when, and why is essential for ensuring that emergency care remains both effective and equitable.

Research Reference:

https://www.neurology.org/