How a Decades-Old Blood Pressure Drug Unexpectedly Shows Promise Against Aggressive Brain Tumors

For more than 70 years, the drug hydralazine has been a familiar presence in medicine cabinets and hospital wards. Doctors have relied on it as one of the earliest and most dependable vasodilators for controlling severely high blood pressure, especially during pregnancy in cases of preeclampsia. Despite its long history, one thing has remained surprisingly unclear: how exactly the drug works at a molecular level. A new study led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania finally answers that question — and reveals a completely unexpected link to glioblastoma, the most aggressive and deadly type of brain tumor.

This discovery is drawing attention not only for solving a decades-old biochemical mystery but also for opening the door to new possibilities in cancer treatment.

And the twist?

The insights came from a very specific, almost accidental observation in the lab.

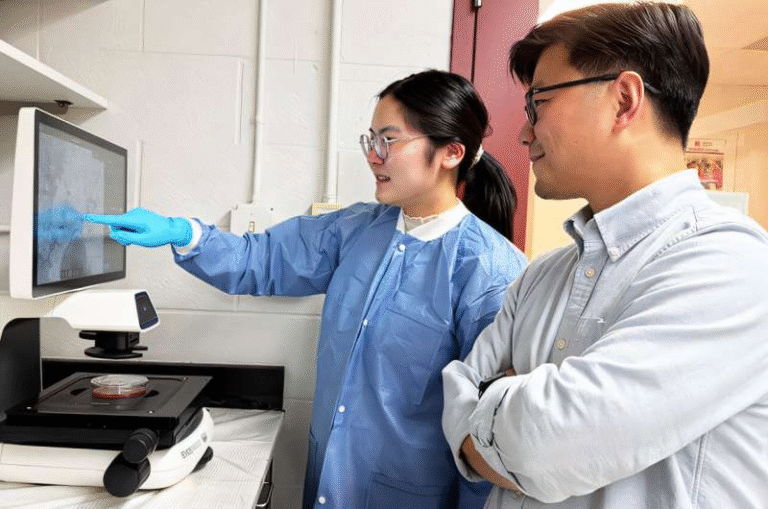

Credit: Kyosuke Shishikura.

Hydralazine’s Mechanism Finally Uncovered

Hydralazine belongs to a class of drugs developed before scientists had the tools to identify precise biological targets. Back then, researchers tested medicines directly in patients and observed the outcomes, figuring out the molecular details later — sometimes much later. This is why hydralazine has been widely used yet poorly understood for generations.

The Penn team has now shown that hydralazine works by blocking an oxygen-sensing enzyme called 2-aminoethanethiol dioxygenase (ADO). This enzyme helps the body detect drops in oxygen levels and signal blood vessels to constrict. ADO acts quickly, flipping a biochemical switch in seconds, making it a crucial regulator of vascular tension.

Hydralazine binds directly to the metal center of ADO, essentially shutting it down. Once ADO is blocked, certain signaling proteins — specifically regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS) — stop being broken down. As RGS proteins accumulate, they tell blood vessels to relax instead of tightening. This lowers intracellular calcium, which is a major controller of smooth muscle contraction in vessel walls. The end result is vasodilation, explaining why hydralazine has been so effective in treating dangerous surges in blood pressure.

This is the first time researchers have mapped out this entire mechanism with molecular-level clarity.

A Surprising Link Between Preeclampsia and Brain Cancer

As the team explored hydralazine’s interaction with ADO, another thread emerged. Scientists studying glioblastoma (GBM) had suspected for some time that ADO might play a major role in how these tumors survive in extremely low-oxygen pockets. Higher levels of ADO and its metabolic byproducts have been associated with more aggressive disease.

However, until now, no strong inhibitor of ADO existed to test this theory. That changed when researchers realized that hydralazine, an old cardiovascular drug, might fit the role perfectly.

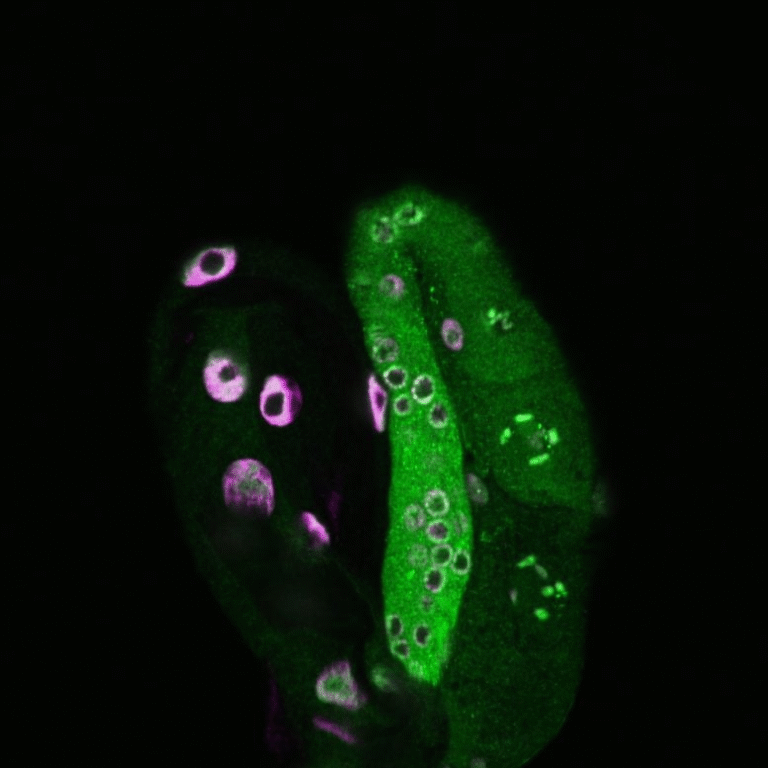

Working with structural biochemists at the University of Texas, researchers used X-ray crystallography to visualize hydralazine attached to ADO. Meanwhile, neuroscientists at the University of Florida tested hydralazine on glioblastoma cells. The results were striking: instead of killing the cancer cells directly, hydralazine pushed them into senescence — a sort of sleep mode where cells stop dividing permanently. These senescent cells became visibly enlarged and flattened, a hallmark of this growth-arrested state.

This means hydralazine isn’t acting like traditional chemotherapy, which often destroys both cancerous and healthy cells. Instead, it disrupts the tumor’s oxygen-sensing machinery, essentially pausing its growth without triggering additional inflammation or resistance pathways. For a cancer as stubborn and adaptable as glioblastoma, even halting growth is a significant breakthrough.

Why This Discovery Matters

This finding is a major reminder of the hidden potential in older, well-established drugs. Hydralazine’s long history means its safety profile is well understood, it is inexpensive compared to modern targeted therapies, and it is already globally accessible. That gives researchers a head start if clinical trials eventually move forward.

More importantly, identifying ADO as a shared target between pregnancy-related hypertension and brain tumor survival opens a new research direction. It creates a biological bridge between two conditions that previously seemed unrelated. Understanding this shared mechanism could lead to better therapies for both maternal health and oncology.

For example, preeclampsia remains a leading cause of complications during pregnancy and contributes to maternal deaths worldwide, especially in regions with limited access to advanced care. Safer, more selective drugs acting on the ADO pathway could improve treatment options and reduce risks.

In cancer research, glioblastoma remains one of the most challenging tumors to treat. Standard treatments like surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy have limited effectiveness and often come with significant side effects. ADO inhibitors — whether hydralazine itself or next-generation versions inspired by it — could represent an entirely new therapeutic strategy.

The Next Steps for Scientists

Now that the mechanism is finally clear, researchers are looking to develop more precise ADO inhibitors. Hydralazine works, but it was never designed with this specific target in mind. The goal is to create drugs that:

- bind more tightly and selectively to ADO

- cross the blood-brain barrier more effectively

- concentrate in tumor tissue rather than affecting the whole body

- minimize side effects, especially during long-term use

Scientists are also investigating whether combining hydralazine-induced senescence with other therapies — such as immune treatments or drugs targeting metabolic pathways — could improve outcomes. In cancer therapy, senescent cells may eventually require removal, so strategies to target them afterward (known as senolytic therapies) could pair well with this approach.

Additional Context: Understanding Glioblastoma and Cellular Senescence

Since this discovery intersects with broader biological themes, here are a few key points that help put the findings into perspective.

What Makes Glioblastoma So Difficult to Treat?

Glioblastoma is one of the fastest-growing brain tumors. Its challenges include:

- deep infiltration into brain tissue

- highly diverse cell populations

- strong survival mechanisms in low-oxygen environments

- rapid genetic changes

Because of these characteristics, even small biological weaknesses in the tumor — such as dependence on an enzyme like ADO — can be extremely valuable in developing new treatment angles.

What Exactly Is Cellular Senescence?

Senescence is a protective mechanism where cells stop dividing to prevent potential damage. In cancer treatment, forcing cells into senescence:

- halts tumor growth

- reduces mutation opportunities

- avoids some harmful effects of chemotherapy

However, senescent cells can sometimes create inflammatory signals, so researchers must balance the benefits and potential drawbacks. In hydralazine’s case, the study suggests it induces senescence without triggering additional inflammation, which is especially promising.

A Broader Lesson in Scientific Discovery

This research underscores the value of revisiting old medicines with modern technology. Many drugs developed before the molecular era have mechanisms that remain only partially understood. As tools like high-resolution imaging, proteomics, and advanced computational modeling continue to evolve, scientists may uncover more hidden therapeutic opportunities.

Hydralazine’s unexpected second role shows that medical progress sometimes comes from looking backward as much as forward. An inexpensive, decades-old drug may end up contributing to one of the most pressing challenges in modern oncology.

Research Paper:

Hydralazine inhibits cysteamine dioxygenase to treat preeclampsia and senesce glioblastoma

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx7687