How a Simple Fiber Found in Vegetables Could Protect — and Even Heal — Your Liver

A new study from researchers at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) has revealed something fascinating: a common dietary fiber called inulin — found in vegetables such as onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, and chicory root — can actually reprogram gut bacteria to block the damaging effects of sugar on the liver.

The findings, published in Nature Metabolism, show that increasing dietary fiber intake doesn’t just support digestion — it can prevent and even reverse liver disease caused by excessive consumption of fructose, a type of sugar abundant in processed foods and sweetened beverages.

What the Researchers Discovered

The study was led by Dr. Cholsoon Jang, an assistant professor of biological chemistry at UC Irvine’s School of Medicine, along with researchers Sunhee Jung, Hosung Bae, and Won-Suk Song. Their team wanted to understand how a natural dietary intervention could help the body counteract the metabolic harm caused by sugar — without relying on drugs.

Their experiments focused on the interaction between dietary fructose and gut bacteria. Fructose is metabolized primarily in the liver, and when consumed in excess, it can lead to hepatic steatosis — better known as fatty liver disease — and can contribute to insulin resistance, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome.

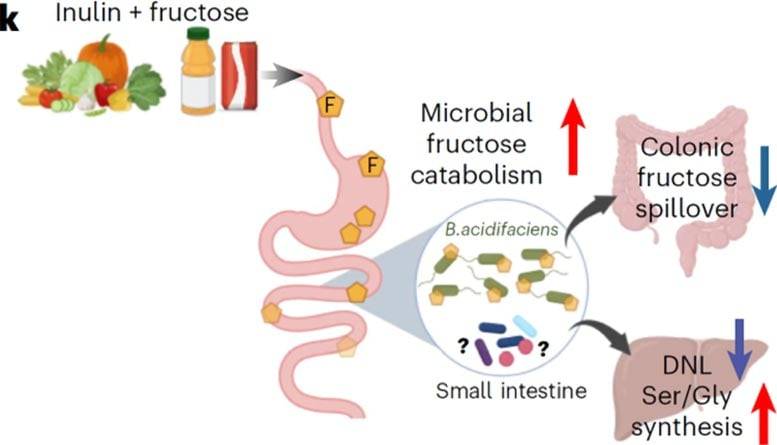

Here’s where inulin comes in. The team discovered that when mice were fed inulin-rich diets, their gut microbiome changed dramatically. Certain bacteria in the small intestine began to consume more of the harmful fructose, essentially “burning it off” before it could travel to the liver. This process reduced the amount of fructose spilling over into the bloodstream and reaching the liver — meaning the liver wasn’t overloaded with sugar and fat production slowed down.

This is important because when fructose overwhelms the liver, it triggers a process called de novo lipogenesis (DNL) — where the liver converts sugar into fat. Over time, that fat builds up, causing inflammation and liver injury.

Inulin, however, redirected this process. By reshaping the bacterial community in the gut, it not only reduced fat buildup but also enhanced the liver’s antioxidant production. This boosted the organ’s natural ability to defend itself from oxidative stress and inflammation.

The Study in Detail

The UC Irvine researchers tested their hypothesis in male mice fed high-fructose diets, a model that mimics the kind of liver damage often seen in humans who consume large amounts of sugary foods and drinks.

The results were striking: increasing inulin intake prevented liver damage and, in some cases, reversed fatty liver disease that had already developed. Even more impressively, when the team transplanted the gut microbiome from inulin-fed mice into other mice suffering from fatty liver disease, those mice also began to recover — even without changing their diet.

This confirmed that it wasn’t just the fiber itself doing the work, but rather the gut bacteria that had adapted to it. These “fiber-friendly” microbes were essentially protecting the liver by consuming fructose before it could do harm.

The study identified that this process occurs primarily in the small intestine, where gut bacteria metabolize dietary fructose early — preventing its passage into the colon and bloodstream. As a result, the liver faced less fructose exposure, leading to lower fat synthesis and higher antioxidant defense.

The liver also increased production of serine and glycine, two amino acids vital for the creation of antioxidants like glutathione. This biochemical shift helped neutralize oxidative stress and prevented liver cell damage.

Why the Findings Matter

Fatty liver disease — or Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) — affects roughly 25–30% of adults worldwide, and rates are rising even among non-obese individuals. Unlike alcoholic liver disease, this condition is driven mainly by excessive sugar intake, particularly fructose from processed foods, soft drinks, and sweeteners like high-fructose corn syrup.

What makes the UC Irvine findings significant is that they show a non-drug, nutrition-based solution for preventing or treating this increasingly common condition. Instead of targeting the liver directly, the researchers are looking at the gut-liver axis — the complex communication system between gut microbes and liver metabolism.

By manipulating the gut environment with the right type of fiber, the liver can be indirectly protected. This opens up exciting possibilities for personalized nutrition strategies, where doctors could assess an individual’s gut bacteria and recommend specific prebiotics or probiotics to optimize fructose processing.

For example, if a person’s microbiome doesn’t efficiently break down fructose, adding the right type of inulin supplement or fiber-rich foods could help strengthen their defense against metabolic damage — all without medication.

What Exactly Is Inulin?

Inulin is a naturally occurring soluble fiber found in many plants. It belongs to a class of carbohydrates known as fructans, made up of chains of fructose molecules. When consumed, inulin isn’t digested by human enzymes; instead, it travels to the lower gut, where it’s fermented by beneficial bacteria.

This fermentation process produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, acetate, and propionate, which help maintain intestinal health, improve insulin sensitivity, and regulate appetite.

Common food sources of inulin include:

- Chicory root (the richest natural source)

- Garlic

- Onions and leeks

- Asparagus

- Jerusalem artichoke

- Bananas

Inulin is also a popular ingredient in prebiotic supplements, often used to promote healthy gut flora.

Previous research has already shown that inulin can reduce cholesterol, stabilize blood sugar, and improve gut barrier function. However, this UC Irvine study adds an entirely new dimension — linking inulin’s microbiome effects directly to liver protection and regeneration.

How Gut Bacteria Play a Role

The human body hosts trillions of bacteria, collectively known as the gut microbiome, which play a crucial role in metabolism, immunity, and even mental health.

When this microbial community is healthy, it supports digestion and nutrient absorption. But when it’s disrupted — by poor diet, antibiotics, or lack of fiber — it can lead to metabolic imbalance and inflammation.

Fructose consumption is particularly damaging because it bypasses normal glucose regulation. Unlike glucose, which triggers insulin responses and is used for energy, fructose is metabolized almost entirely by the liver. Excess fructose is converted to fat, and over time, this process can lead to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance, and even type 2 diabetes.

The UC Irvine study demonstrates that gut bacteria can act as a buffer against this overload. By breaking down fructose earlier in the digestive process, they prevent it from reaching the liver in harmful quantities.

This means the gut microbiome could be harnessed as a tool for metabolic disease prevention — through diet, probiotics, or targeted prebiotics like inulin.

Looking Ahead

The UC Irvine team plans to explore whether other types of dietary fiber can produce similar benefits. Fibers vary widely — some are fermentable like inulin, while others, such as cellulose, are not. Understanding how different fibers shape gut metabolism could lead to tailored dietary plans for preventing obesity, diabetes, fatty liver disease, and even cancer.

They also hope to translate these findings into human trials, since all current results come from controlled experiments in mice. While animal studies are a powerful tool for understanding biological mechanisms, human gut ecosystems are more complex and diverse.

There’s also the question of dosage — how much inulin would be required to achieve a protective effect in humans? Excessive inulin can cause gas, bloating, or digestive discomfort, especially for people with sensitive guts or irritable bowel conditions. So, the challenge will be finding the right balance — enough to benefit the microbiome and liver, without triggering side effects.

Another key area of future research will involve identifying the specific bacterial strains that respond best to inulin. If scientists can pinpoint which microbes are responsible for fructose metabolism, they could design targeted probiotic formulations or microbiome transplants for patients with liver disease.

Why This Matters Beyond the Liver

This discovery isn’t just about liver health — it’s about how nutrition and the microbiome can reshape modern medicine. Instead of simply treating diseases after they develop, scientists are exploring ways to prevent illness through gut ecology.

In recent years, the microbiome has been linked to nearly every major health domain — from obesity and heart disease to mood disorders and immunity. This research from UC Irvine adds another piece to that puzzle, highlighting how a simple dietary change can have system-wide effects on metabolism and inflammation.

Ultimately, this study reinforces a simple message: what we eat doesn’t just feed us — it feeds our microbes, and in turn, they protect us. Choosing foods rich in natural fibers like inulin could be one of the most accessible ways to improve metabolic health in a world overflowing with sugar.

Research Reference

Nature Metabolism (2025): Dietary fibre-adapted gut microbiome clears dietary fructose and reverses hepatic steatosis