How Our Brains Read Emotions Differently And Why Some People Are Better at Reading the Room

Understanding other people’s emotions feels effortless for some and frustratingly unclear for others. A new UC Berkeley study sheds light on why this gap exists, showing that people don’t all process emotional information in the same way. The research reveals that while most brains perform a complex calculation when reading emotions, a significant portion rely on a simpler shortcut, leading to noticeable differences in social understanding.

Why Reading the Room Is Not the Same for Everyone

When we interact with others, our brains constantly combine information from facial expressions, body language, and the surrounding context. A smile, a frown, the setting, and even other people in the background all contribute to how we interpret someone’s emotional state.

The Berkeley researchers found that people differ fundamentally in how they combine these signals. Some people are naturally skilled at evaluating which cues are reliable and which are not, while others treat all emotional information as equally important, even when it isn’t.

These differences may explain why some individuals are remarkably good at reading emotions, while others often walk away from conversations feeling unsure or confused.

How the Brain Combines Facial Expressions and Context

In everyday life, emotional cues are rarely perfectly clear. A person might look upset but be standing in a joyful environment, or they may have a neutral expression while surrounded by emotionally charged circumstances.

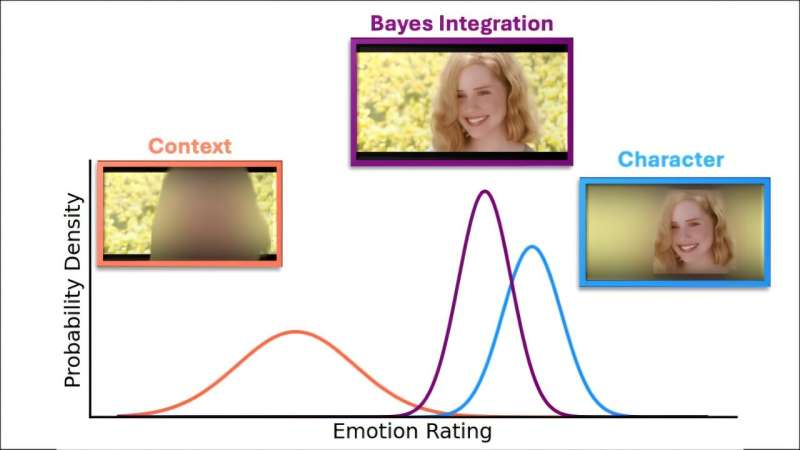

The brain typically solves this problem by weighing cues based on how clear or ambiguous they are. If a facial expression is obvious but the background context is unclear, the face usually matters more. If the face is hard to read but the environment strongly suggests an emotion, the context takes priority.

This flexible process allows people to adapt their judgments depending on the situation. The researchers describe this as a Bayesian-style integration, meaning the brain uses probability-like reasoning to decide which information deserves more weight.

Inside the UC Berkeley Study

The research team, led by psychology doctoral researcher Jefferson Ortega and conducted in collaboration with David Whitney, a professor of psychology at UC Berkeley, designed an experiment to isolate how people process emotional information.

A total of 944 participants took part in the study. They were shown a series of short video clips featuring a person in different emotional situations. Some videos had clear faces but blurred backgrounds, while others had blurred faces but clear contextual surroundings.

Participants were asked to continuously rate the emotional state of the person in each clip. This setup allowed researchers to separately measure how people responded to facial cues and contextual cues, and then predict how they should respond when both were visible at the same time.

By comparing these predictions to participants’ actual responses, the researchers could determine how individuals combined emotional information.

Two Distinct Emotional Processing Strategies

The results revealed a clear split in how people process emotional cues.

About 70% of participants behaved as expected. They adjusted their judgments based on which information was clearer in each situation. When faces were blurred, they relied more on context. When the background was unclear, facial expressions carried more weight. This group demonstrated adaptive, flexible integration, closely matching the Bayesian model.

However, the remaining 30% of participants showed a very different pattern. Instead of adjusting their strategy based on ambiguity, they appeared to average facial and contextual cues equally, regardless of clarity. This meant they did not prioritize the most informative signal in a given scene.

This simpler approach required less mental effort, but it also reduced accuracy in emotionally complex situations.

Why Some Brains Take a Shortcut

The researchers do not yet know exactly why this difference exists, but they propose several possible explanations. One is that the simpler averaging strategy may be less cognitively demanding, making it appealing for some brains.

Another possibility is that underlying cognitive differences affect how people integrate information. The brain mechanisms responsible for weighing uncertainty may vary from person to person, leading to different emotional processing styles.

What surprised the researchers most was how consistent these patterns were. The difference wasn’t random or situational. It reflected a stable, individual-level strategy for interpreting emotions.

Implications for Social Skills and Everyday Life

These findings help explain why social interactions feel effortless for some people and challenging for others. Someone who can quickly identify which cues matter most is more likely to interpret emotions accurately, especially in complex or ambiguous situations.

On the other hand, someone who treats all emotional cues equally may struggle when signals conflict. This can lead to misunderstandings, uncertainty, or misinterpretation of social situations.

Importantly, this does not mean one strategy is inherently “wrong.” Simpler strategies may work well in straightforward situations, but they become less effective when emotional signals are mixed or unclear.

Connections to Autism and Neurodiversity

The study also builds on Ortega’s earlier research into individuals with traits associated with autism. Previous findings suggest that some autistic individuals may find it more difficult to integrate facial expressions and context when interpreting emotions.

This new research raises important questions about which integration strategies different individuals use and how these strategies shape social perception. Understanding these differences could eventually help researchers better describe the diversity of emotional processing styles across the population.

Rather than framing emotional differences as deficits, the study highlights them as variations in information-processing strategies, offering a more nuanced view of social cognition.

Why Context Matters More Than We Think

Past research from the Whitney Lab has already shown that people can often infer emotions from context alone, even when faces are blurred or hidden. This underscores how powerful environmental cues can be in shaping emotional judgments.

A crying face might suggest sadness, but when paired with a wedding altar, the emotional meaning shifts dramatically. The brain’s ability to resolve these contradictions is essential for navigating real-world social situations.

This study reinforces the idea that emotion perception is not just about faces. It is about integrating multiple sources of information in a dynamic and flexible way.

Broader Insights Into How the Brain Handles Uncertainty

Beyond emotion, the findings touch on a larger theme in cognitive science: how humans deal with uncertainty and ambiguity. The brain often relies on shortcuts, known as heuristics, to make quick decisions. While these shortcuts are efficient, they can sometimes sacrifice accuracy.

The contrast between Bayesian integration and simple averaging offers a clear example of how different brains balance effort and precision. This balance likely extends beyond emotions into areas such as decision-making, perception, and judgment.

What This Research Adds to Our Understanding of Human Behavior

This study provides strong evidence that people differ not just in social skill, but in the underlying computations their brains use to interpret emotional information. These differences are measurable, consistent, and meaningful.

By identifying distinct emotional integration strategies, the research opens new avenues for studying social perception, cognitive diversity, and emotional understanding.

Most importantly, it reminds us that when someone struggles to read emotions, it may not be a lack of effort or care, but a difference in how their brain processes the world.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67466-1