How Supercomputers Are Helping Scientists Pinpoint New Treatment Targets for Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease affects more than one million people in the United States, causing symptoms like tremors, slowed movement, stiffness, and changes in speech. It is a degenerative and currently incurable neurological disorder, and its impact goes far beyond physical health. Families deal with emotional stress, patients face declining independence, and health systems absorb enormous costs. In California alone, Parkinson’s-related health care expenses and lost productivity are estimated to exceed $6 billion.

For decades, scientists have tried to understand what exactly goes wrong in the brain to produce these symptoms. While the loss of dopamine-producing neurons has long been recognized as a key factor, it has never fully explained all aspects of the disease. One of the biggest mysteries has involved unusual patterns of brain activity known as beta waves—rhythmic electrical signals around 15 hertz that appear abnormally strong in people with Parkinson’s disease. Now, thanks to advanced supercomputer simulations, researchers may finally have a clearer answer.

The Longstanding Mystery of Beta Waves in Parkinson’s Disease

Beta waves are a normal part of brain activity and play a role in movement control. In healthy brains, they rise and fall as needed. In Parkinson’s disease, however, beta waves become excessively strong and persistent, especially in regions involved in motor control. This abnormal activity has been closely linked to symptoms like rigidity and slowed movement.

Although beta waves have been observed for years using brain imaging and electrophysiological recordings, scientists did not fully understand where these waves originate or why they become amplified in Parkinson’s disease. Previous theories focused heavily on deep brain structures such as the basal ganglia, but these explanations left important gaps.

That is where supercomputing entered the picture.

Using Supercomputers to Model a Parkinsonian Brain

Researchers working within the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Collaborative Research Network used powerful computing resources from the U.S. National Science Foundation’s ACCESS program to tackle this problem. Their simulations ran on Expanse, a high-performance supercomputer housed at the San Diego Supercomputer Center, which is part of the University of California San Diego’s School of Computing, Information, and Data Sciences.

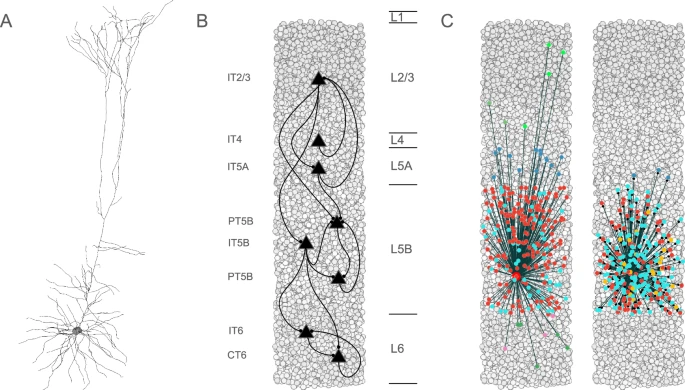

The team, led in part by Donald W. Doherty, a research scientist at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, built detailed computer models of the primary motor cortex, a brain region critical for voluntary movement. These models were grounded in real biological data obtained from rodent models of Parkinson’s disease, ensuring that the simulations reflected realistic neural behavior rather than abstract math.

The goal was simple but ambitious: determine which specific brain cells might be responsible for triggering abnormal beta wave activity.

The Surprising Role of PT5B Neurons

The simulations pointed to a very specific culprit: PT5B neurons, also known as layer 5B pyramidal tract neurons. These neurons are located in the primary motor cortex and play a crucial role in sending movement-related signals from the cortex to other parts of the brain and spinal cord.

What the researchers discovered was striking. When the activity of PT5B neurons was reduced even slightly, the entire motor network became disrupted. This reduction created a kind of bottleneck, interfering with how information flowed across the brain’s motor system.

As a result, beta wave power increased dramatically throughout the network. In other words, a relatively small dysfunction in one specific neuron type was enough to produce the abnormal brain rhythms that have long been associated with Parkinson’s disease.

This finding suggests that PT5B neurons are not just affected by Parkinson’s disease—they may be central drivers of its motor symptoms.

Why This Discovery Matters

Most current Parkinson’s treatments focus on replacing dopamine or stimulating broad brain regions to ease symptoms. Medications like levodopa help replenish dopamine levels, while techniques such as deep brain stimulation aim to regulate abnormal activity in large neural circuits.

While these treatments can be effective, they do not address the disease at a cell-specific level, nor do they stop disease progression. The new findings suggest a different approach: targeting PT5B neurons directly.

By identifying a single neuron type that strongly influences beta wave activity and motor control, researchers now have a clearer and more precise therapeutic target. Instead of broadly altering brain chemistry or stimulation patterns, future therapies could aim to restore normal PT5B neuron function or compensate for their loss.

This could potentially lead to treatments that address the root cause of motor dysfunction, rather than simply managing symptoms.

What the Simulations Revealed About Brain Networks

Another important insight from the study is how small cellular changes can have large system-wide effects. The simulations showed that dysfunction in PT5B neurons does not stay localized. Instead, it ripples outward, affecting communication across the entire motor cortex and beyond.

This helps explain why Parkinson’s symptoms can be so widespread and why motor impairment often worsens over time. It also highlights the importance of understanding the brain as an interconnected network, where changes in one node can destabilize the whole system.

Supercomputing made this possible by allowing researchers to test scenarios that would be impossible or unethical to recreate in living brains.

The Growing Role of Supercomputers in Neuroscience

This study is part of a broader shift toward computational neuroscience, where large-scale simulations complement traditional lab experiments. Supercomputers allow scientists to explore how thousands—or even millions—of neurons interact under different conditions.

In diseases like Parkinson’s, where human brain tissue is difficult to study directly, these simulations provide a powerful way to bridge the gap between animal models and human patients. They also help researchers generate testable hypotheses that can later be explored in clinical or laboratory settings.

As computing power continues to grow, its role in understanding complex brain disorders is likely to expand even further.

Understanding Parkinson’s Beyond Dopamine

While dopamine loss remains a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease, this research reinforces the idea that Parkinson’s is not solely a dopamine problem. It is a network disorder, involving changes in electrical signaling, neuron communication, and cortical function.

Beta waves, once seen mainly as a symptom, may actually be a key mechanism driving movement impairment. By identifying how and where these waves emerge, scientists can better design interventions that restore healthy brain rhythms.

Looking Ahead

The ASAP Collaborative Research Network hopes to build on these findings by exploring ways to translate them into clinical treatments. That could involve developing drugs that protect or enhance PT5B neuron function, refining brain stimulation techniques to target specific cortical layers, or designing entirely new therapeutic strategies.

While these approaches are still in development, the research represents a meaningful step toward more precise and personalized treatments for Parkinson’s disease.

For millions of patients and families affected by this condition, understanding what goes wrong at the cellular level brings renewed hope that future therapies could do more than manage symptoms—they could fundamentally change how Parkinson’s disease is treated.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41531-025-01070-4