How the Brain and Immune System Work Together to Make Us Avoid Social Contact When We’re Sick

A new study from researchers at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, together with collaborators from Harvard Medical School, uncovers the exact biological pathway that makes animals — and likely humans — pull back from social interaction during illness. Instead of social withdrawal being just a side effect of feeling tired or weak, this research shows it is an active, brain-driven behavior triggered by the immune system. The work, recently published in Cell, maps out the specific cytokine, receptor, neurons, and brain circuit responsible for this well-known sickness behavior.

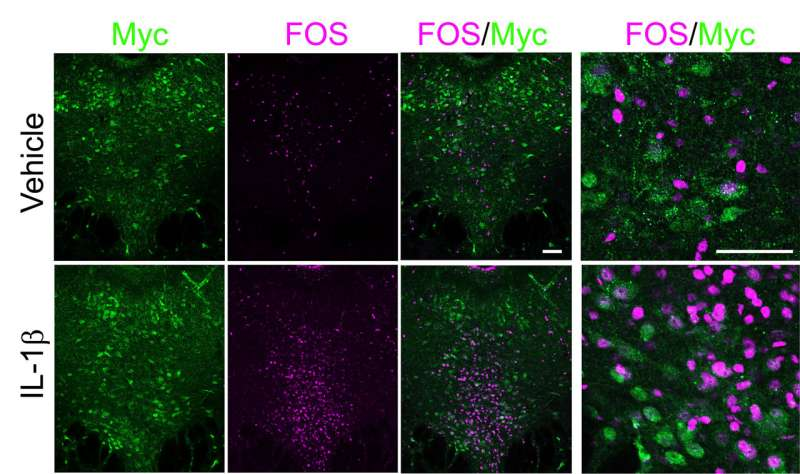

At the center of the discovery is the immune molecule Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). The researchers began by testing 21 different cytokines to see which ones could reproduce the same social-avoidance effects typically caused by an infection-mimicking agent called LPS. Out of all the cytokines tested, only IL-1β was able to fully trigger the same social withdrawal seen during immune challenge. It also made mice show general sluggishness, but the team was careful to separate lethargy from the specific decision to avoid social contact.

Credit: Cho Lab/MIT Picower Institute

The next key piece of the puzzle was determining where in the brain IL-1β acts. Cytokines affect cells only when they bind to their matching receptors, and the receptor for IL-1β is IL-1R1. The researchers scanned the brain to find where IL-1R1 was expressed and identified several regions, but one area stood out: the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN). The DRN is well known for regulating social behavior, and it sits right beside the cerebral aqueduct — a channel carrying cerebrospinal fluid, which likely delivers circulating cytokines directly to this region. That made it a strong candidate for mediating sickness-related social changes.

Within the DRN, the team pinpointed neurons that express IL-1R1, including many that produce serotonin, a neuromodulator deeply involved in mood and social regulation. The researchers demonstrated that IL-1β directly activates these IL-1R1-expressing neurons. When they artificially activated these neurons, mice showed clear social-withdrawal behavior. When they inhibited them, the social-withdrawal response to IL-1β disappeared. Even more striking, when IL-1R1 was removed specifically from these neurons, mice no longer withdrew socially in response to either IL-1β injection or LPS exposure.

However, none of these manipulations altered the physical sluggishness caused by IL-1β or LPS. This was a critical result: it showed that social withdrawal and lethargy are driven by different biological pathways, and social withdrawal is not just a passive consequence of low energy. According to the researchers, IL-1β is a primary driver of the decision to avoid others during sickness.

Once the team identified the DRN as the key site where IL-1β acts, they investigated which brain circuits these neurons use to influence social behavior. Using tracing methods, they examined where the IL-1R1-positive DRN neurons send their signals. Several downstream regions were identified, but the researchers needed to know which one actually controlled social withdrawal. For this, they turned to optogenetics, a technique that allows specific neurons and circuits to be activated with targeted flashes of light.

They tested the DRN’s projections to multiple regions involved in social processing. Only one connection — from the DRN to the intermediate lateral septum — reproduced the full social-avoidance behavior when activated. None of the other connected regions produced the same effect. This allowed the researchers to map a clear functional circuit: IL-1β → IL-1R1 DRN neurons → intermediate lateral septum → social withdrawal.

To make sure this pathway isn’t just artificially activated in lab conditions, the researchers repeated the experiments using actual Salmonella infection. The results were consistent: the same IL-1R1 DRN pathway was required for infection-driven social withdrawal, confirming the biological relevance of the circuit.

The study raises several new questions. One major question is whether IL-1R1 DRN neurons influence other sickness-related behaviors beyond social avoidance. For example, symptoms like appetite suppression, fever response, or changes in sleep might involve distinct circuits, or they might share partial overlap with the social-withdrawal pathway. Another open question is the role of serotonin. Since many of the IL-1R1 DRN neurons are serotonergic, serotonin release could be part of how sickness modifies behavior — but this remains to be confirmed.

This research adds to a broader body of scientific work showing that the immune system and brain communicate far more directly and precisely than once believed. Cytokines are often thought of only as molecules involved in inflammation, but they also function as powerful neuromodulators that can reshape motivation, decision-making, and social behavior. Similar immune-brain interactions have been linked to depression, fatigue, cognitive fog, and altered reward processing during illness.

The discovery that a single cytokine-receptor interaction can drive a highly specific behavioral outcome strengthens the idea that sickness behaviors are adaptive features rather than accidental side effects. From an evolutionary standpoint, temporarily avoiding social environments when sick reduces the likelihood of spreading infection and helps conserve energy for recovery. This new research provides a clear biological explanation for how the body implements that behavioral strategy.

Beyond the immediate findings, this study may contribute to understanding conditions where inflammation and social behavior intersect. Chronic inflammatory disorders often come with social-withdrawal symptoms, and certain psychiatric conditions — including depression and social anxiety — have been linked to elevated inflammatory markers. Understanding this IL-1β-driven pathway could eventually guide research aimed at disentangling pathological social withdrawal from adaptive, infection-related withdrawal.

While the study was performed in mice, many aspects of IL-1β signaling and DRN circuitry are conserved across mammals. This raises the possibility that humans experience similar cytokine-induced behavioral regulation. The next steps for researchers may involve determining whether blocking IL-1R1 or its downstream circuits could selectively alter social behavior during persistent inflammation — without interfering with essential immune functions.

To give more background for readers, IL-1β is one of the earliest cytokines released by the immune system during infection. It can circulate through the blood, cross into the brain via specialized transport processes, and activate receptors in brain regions involved in motivation, stress responses, and social behavior. The dorsal raphe nucleus, meanwhile, is a major center for serotonin production and has been studied extensively for its roles in mood regulation, aggression, reward, and the effects of stress. The lateral septum, the downstream target identified in this study, is known for shaping social memory, emotional responses, and context-dependent social behavior.

Putting these pieces together, the pathway described in the new research fits neatly into larger frameworks already known to scientists. It shows how the immune system can push the brain to reorganize social priorities during sickness, using well-defined neural architecture rather than vague or generalized whole-brain states.

The study’s authors emphasize that although this work reveals a complete cytokine-to-brain-to-behavior pathway, many mysteries remain. They still need to explore how long this pathway remains active during infection, how it interacts with hormonal stress responses, whether it modifies learning or memory about social environments, and whether chronic activation of this system could contribute to long-term social dysfunction.

But this research represents one of the clearest mechanistic explanations to date for a behavior that almost everyone recognizes from personal experience: when we’re sick, we just don’t want to be around other people. And now, for the first time, we know precisely why.

Research Reference:

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)01245-0