How the Brain Turns a Stream of Sounds Into Words and Why Foreign Languages Often Feel Like a Blur

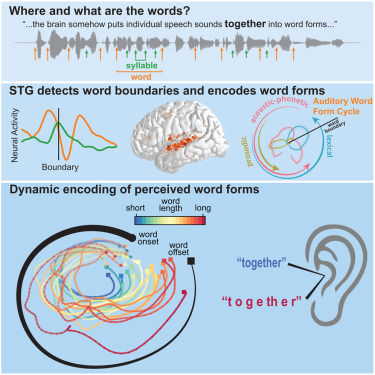

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have released two major 2025 studies that explain a question most language learners wrestle with: why speech in a foreign language sounds like one long, indistinguishable stream, while our native language feels crisp and neatly segmented. Their findings reshape long-held assumptions about how the brain processes spoken language and reveal new details about a region called the superior temporal gyrus (STG). This brain area, previously thought to focus mostly on simple sound recognition, turns out to play a much deeper role in identifying where one word ends and the next begins.

The new work, led by neurosurgeon Edward Chang and published in both Neuron and Nature, shows that the STG contains specialized neurons that learn word-boundary patterns through years of exposure to a language. These neurons behave differently depending on whether a listener is hearing a familiar or unfamiliar language, which helps explain why foreign languages initially feel fast, blurred, and impossible to segment.

Below is a clear breakdown of all the core findings, the methodology behind them, and additional background information on how the brain processes speech and language.

How the Brain Learns Word Boundaries

When people speak naturally, they do not insert silent gaps between words, even though listeners effortlessly perceive them. For a long time, researchers assumed higher-level language regions—areas associated with meaning—were responsible for figuring out where words begin and end. But the new studies shift the focus to the STG, a region long associated with analyzing basic acoustic features like vowels and consonants.

The UCSF team demonstrated that neurons in the STG actually learn the sound patterns, timing cues, and prosodic structures of a language. Over time, they form reliable predictions about what words look and sound like. Once the brain has these templates, it can split continuous speech into meaningful units extremely quickly.

The researchers described the process as a kind of rapid reset: the STG neurons activate while processing a word, then fall silent and reset just in time to detect the next one. This rapid cycle—happening several times per second—allows fluent listeners to keep up with fast, natural speech.

What the Nature Study Found

One of the two studies recorded brain activity from 34 volunteers undergoing clinical monitoring for epilepsy. These participants spoke Spanish, Mandarin, or English as their native language. Eight were bilingual, but none spoke all three. This gave the researchers a clean way to compare neural activity between familiar and unfamiliar languages.

Participants listened to spoken sentences in all three languages.

The results were striking:

- When listeners heard their native language or a language they knew, STG neurons that track word boundaries lit up immediately.

- When they heard a language they did not understand, those neurons were far less active or did not engage in the same pattern.

The difference was not subtle. The brain clearly showed a distinction between languages with learned word-boundary cues and languages that lacked those learned patterns.

This helps explain a familiar feeling: when you hear a foreign language, it seems like the speaker isn’t pausing. But in reality, your brain simply has not yet learned the boundary signatures of that language.

One of the study authors noted that this ability gives insight into “the magic that allows us to understand what someone is saying,” which now seems less magical and more rooted in years of auditory experience.

What the Neuron Study Found

The second study zeroed in on how exactly these neurons identify beginnings and endings of words.

Key findings include:

- STG neurons exhibit a precise response pattern when a word begins.

- They then reset rapidly after the word ends so they can catch the next word.

- This rapid reset is essential because fluent speech contains several words per second.

- Without this mechanism, continuous speech would overwhelm the system.

The researchers described the process as similar to a reboot happening several times per second. The brain essentially completes processing a recognized word, clears its working buffers, and prepares for the next sound sequence.

The studies also shed light on how injuries to the STG can cause difficulty understanding speech even when hearing itself remains normal. Damage to these regions disrupts the brain’s ability to segment words, leaving speech perceptually intact but cognitively chaotic.

Why Foreign Languages Sound Fast and Blurry

These findings help clarify a universal experience among language learners. When you first hear a foreign language, you cannot rely on familiar sound patterns, typical word lengths, or predictable phonological transitions. Without those learned templates, the STG cannot trigger the rapid word-boundary resets needed for clean segmentation.

As a result:

- All words appear to run together.

- Speech feels too fast, even when spoken slowly.

- Individual words are nearly impossible to identify.

This is why beginners often say a new language sounds like a single long word. The challenge is not just vocabulary—it’s the brain lacking years of exposure-based training that native speakers rely on.

Over time, as learners hear thousands of hours of speech, the STG gradually acquires the sound patterns of the new language, making the “blur effect” fade.

How the Research Fits Into Broader Language Science

To give readers additional context, here are broader insights about speech perception and the brain:

The Brain Doesn’t Hear Words—It Builds Them

Spoken language doesn’t naturally contain spaces, and different speakers vary in speed, accent, and intonation. The brain uses statistical patterns, timing, and learned cues to carve continuous sound into discrete units.

Word Segmentation Develops Over Years

Newborns can distinguish some phonetic contrasts, but true word segmentation takes years of repeated exposure. This continues into adulthood for any new language.

Prosody Helps but Is Not Enough

Languages differ in rhythm and stress patterns. English is stress-timed, Spanish is syllable-timed, and Mandarin blends tonal contrasts with rhythmic structure. The STG tunes itself to these patterns and uses them for segmentation.

Bilingual Brains Have Multiple Templates

The Nature study shows that bilingual individuals naturally activate different neural patterns depending on which language they are hearing. This supports research showing that bilingual brains maintain separate but overlapping processing systems.

Implications for Language Disorders

Understanding how the STG processes word boundaries may help treat:

- Certain forms of aphasia

- Language comprehension deficits

- Developmental speech disorders

Implications for Technology

These findings could advance:

- Brain-computer interfaces for speech decoding

- More human-like speech recognition algorithms

- Neural prosthetics for people with impaired language functions

The UCSF team’s work provides a new blueprint for building systems that recognize speech more like humans do—by understanding the dynamic boundaries between words, not just individual sounds.

Research Reference

Human cortical dynamics of auditory word form encoding (Neuron, 2025)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2025.10.011