How the Brain’s Antiviral Defense Mechanism May Be Contributing to Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease has long been associated with the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain, especially amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles. For decades, these features were viewed almost entirely as harmful byproducts of disease. New research, however, is challenging that assumption in a fascinating way. A recent study from researchers at Mass General Brigham suggests that one of the most well-known Alzheimer’s-related proteins, phosphorylated tau, may actually be part of the brain’s antiviral defense system. The problem is that what once helped protect the brain might, over time, contribute to neurodegeneration.

Understanding Tau and Why It Matters in Alzheimer’s

Tau is a protein normally found inside neurons, where it helps stabilize structures known as microtubules. These structures are essential for transporting nutrients and signals within nerve cells. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau undergoes a chemical change called hyperphosphorylation, meaning too many phosphate groups attach to the protein.

When this happens, tau loses its ability to support microtubules and instead begins sticking to other tau molecules. Over time, these clumps form neurofibrillary tangles, one of the defining pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease. These tangles disrupt neuron function and are strongly linked to cognitive decline.

Until recently, hyperphosphorylated tau was almost universally considered a purely pathological process. The new findings suggest the story may be more complicated.

A Surprising Link Between Tau and Viral Infection

The new study, published in Nature Neuroscience, explored how tau behaves when neurons are exposed to viral infection. The researchers focused on herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), a very common virus best known for causing cold sores but also capable of infecting the nervous system.

Using a human-derived neuron cell culture model designed to closely mimic how tau behaves in the brain, scientists exposed neurons to HSV-1. What they observed was striking. Infection with the virus triggered rapid hyperphosphorylation of tau, leading to the formation of aggregates that closely resembled Alzheimer’s-related tangles.

Rather than being a random or damaging side effect, this response appeared to serve a purpose.

Phosphorylated Tau as an Antiviral Protein

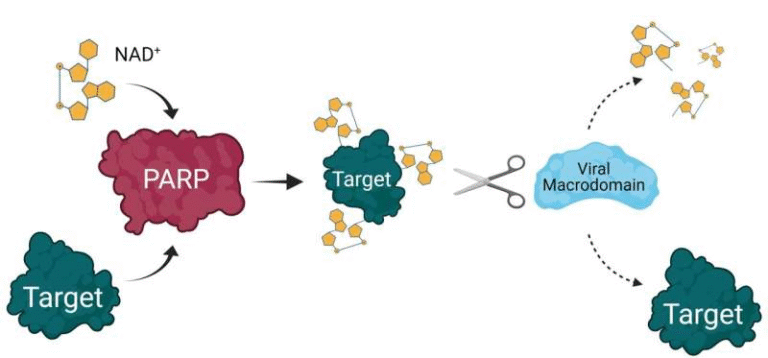

One of the most important discoveries from the study was that phosphorylated tau can directly bind to the HSV-1 viral capsid, which is the protein shell that protects the virus’s genetic material. By attaching itself to the virus, tau effectively neutralized HSV-1, preventing it from infecting additional neurons.

This means tau was not just reacting to infection but actively participating in the brain’s immune defense. In this context, tau behaved much like an antimicrobial or antiviral protein, trapping the virus and limiting its spread.

Even more interesting was the discovery of a feedback mechanism. Neurons infected with HSV-1 released hyperphosphorylated tau as tangles formed. That released tau then went on to bind more virus particles, creating a cycle in which tau aggregation helped contain infection within the brain.

Rethinking Alzheimer’s as an Evolutionary Trade-Off

The findings fit into a broader hypothesis that has been developing over the past several years. Researchers, including the senior author of this study, have proposed that Alzheimer’s pathology may have evolved as a protective response rather than as a disease-specific malfunction.

Earlier work from the same research group demonstrated that amyloid beta, the main component of Alzheimer’s plaques, also has antimicrobial properties. Amyloid beta can trap and neutralize bacteria and viruses, much like phosphorylated tau appears to do.

From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. For much of human history, average life expectancy was around 30 years. During that time, surviving infections would have been a major selective advantage. Genetic traits that enhanced brain immunity, even at the cost of long-term damage, could have been beneficial.

As human lifespan increased, these same mechanisms may have become problematic. What once protected the brain from infection now has decades to accumulate, eventually contributing to neurodegeneration and dementia.

Why HSV-1 Is Especially Relevant

HSV-1 is particularly interesting in Alzheimer’s research because it is extremely common, with most adults worldwide carrying the virus in a dormant form. The virus can periodically reactivate, especially during stress or immune suppression.

Multiple studies have detected HSV-1 DNA and proteins in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, often in regions heavily affected by tau tangles. The new findings help explain why this association might exist. If tau aggregation is part of the brain’s response to viral invasion, repeated or chronic viral activity could continuously trigger tau hyperphosphorylation.

Over time, this repeated immune response could push tau from being protective to being pathological.

What This Means for Alzheimer’s Treatments

These discoveries raise important questions about how Alzheimer’s should be treated. Many experimental therapies aim to remove tau tangles or prevent tau phosphorylation altogether. If phosphorylated tau plays a role in antiviral defense, completely blocking this process could have unintended consequences.

This does not mean tau tangles are harmless. In aging brains, excessive accumulation clearly disrupts neuron function. However, it suggests that future treatments may need to be more precise, targeting harmful tau buildup while preserving any beneficial immune roles.

It also opens the door to exploring whether antiviral therapies or better management of latent infections could reduce Alzheimer’s risk in certain individuals.

The Bigger Picture of Brain Immunity

The brain was once thought to be largely isolated from the immune system. Modern neuroscience has overturned that idea. We now know the brain has its own innate immune defenses, involving microglia, inflammatory signaling pathways, and, as this study suggests, proteins like tau and amyloid beta.

Tau’s newly identified antiviral activity adds another layer to our understanding of how closely immunity and neurodegeneration are intertwined. Alzheimer’s may not be caused by a single factor but by a complex interaction between genetics, aging, immune responses, and environmental triggers such as infections.

Key Takeaways from the Study

The research shows that HSV-1 infection can trigger tau hyperphosphorylation in human neurons.

Phosphorylated tau can bind directly to viruses and neutralize them.

Tau tangles may have originally formed as a way to limit viral spread in the brain.

Alzheimer’s-related pathology may represent an overactive or misdirected immune response rather than a purely toxic process.

These insights do not rewrite everything we know about Alzheimer’s disease, but they significantly expand the framework. They suggest that what we label as disease today may be the unintended outcome of ancient survival mechanisms operating in a modern, long-lived population.

Research Reference

Eimer WA et al. “Phosphorylated tau exhibits antimicrobial activity capable of neutralizing herpes simplex virus 1 infectivity in human neurons.” Nature Neuroscience (2025).

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-025-02157-0