How the Prefrontal Cortex Reaches Back to Shape Vision and Movement Processing in the Brain

A new study from MIT offers a detailed look at how the brain’s prefrontal cortex (PFC) communicates with regions responsible for vision and movement, revealing that this communication is far more specialized and targeted than previously understood. Instead of broadcasting a general control signal, the PFC uses distinct circuits to fine-tune how other brain regions work depending on an animal’s arousal, movement, and behavioral context.

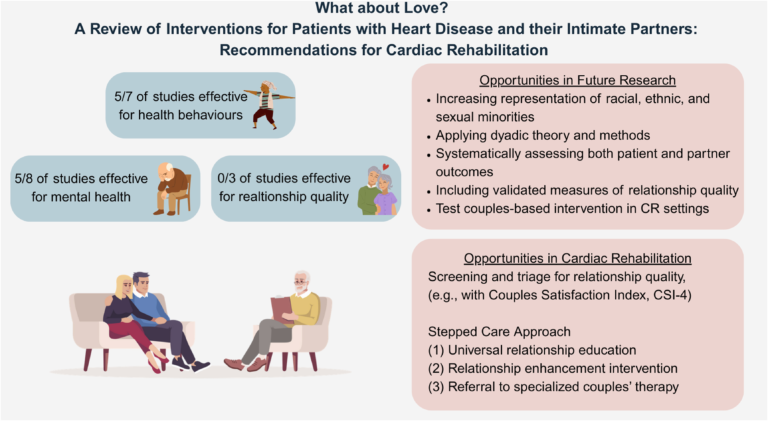

This research, published in Neuron, focuses on two specific PFC subregions—the anterior cingulate area (ACA) and the orbitofrontal cortex (ORB)—and how they send tailored messages to the primary visual cortex (VISp) and the primary motor cortex (MOp). The findings challenge older assumptions that the PFC simply sends broad top-down modulation and instead reveal a highly organized system that shapes perception and behavior in precise ways.

Clear Functional Differences Between ACA and ORB

The study demonstrates that the ACA and ORB do not perform the same job. Though both are part of the prefrontal cortex, each sends different kinds of information to their target regions.

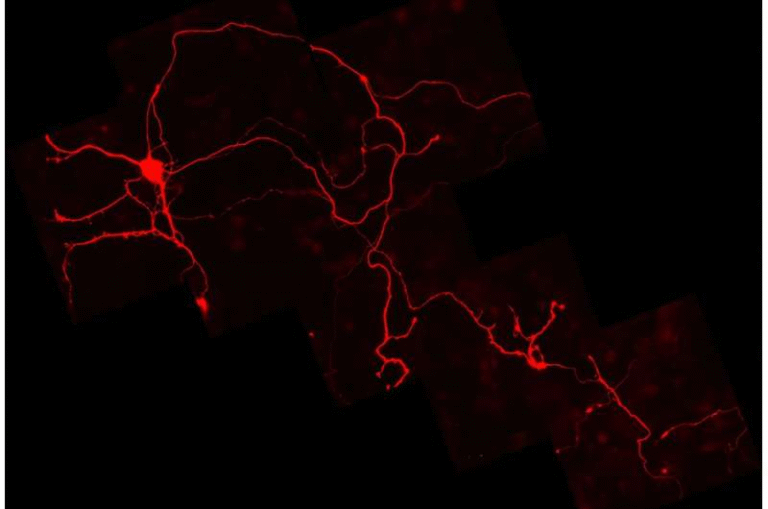

Credit: Sur Lab/MIT Picower Institute

ACA’s role:

- Conveys significantly more visual information to VISp than ORB does.

- Displays high sensitivity to contrast in visual stimuli.

- Adjusts its activity continuously with arousal level—the more aroused the mouse becomes, the stronger and more focused ACA’s feedback becomes.

ORB’s role:

- Responds mainly when arousal crosses a higher threshold, suggesting it monitors extreme internal states.

- Contributes less visual detail, and instead transmits signals that help reduce or dampen unwanted visual input when arousal becomes too high.

- May help the brain ignore strong but irrelevant stimuli, preventing sensory overload.

This separation of duties allows the brain to balance enhancement and suppression, depending on what the animal is experiencing internally.

How the Experiments Were Conducted

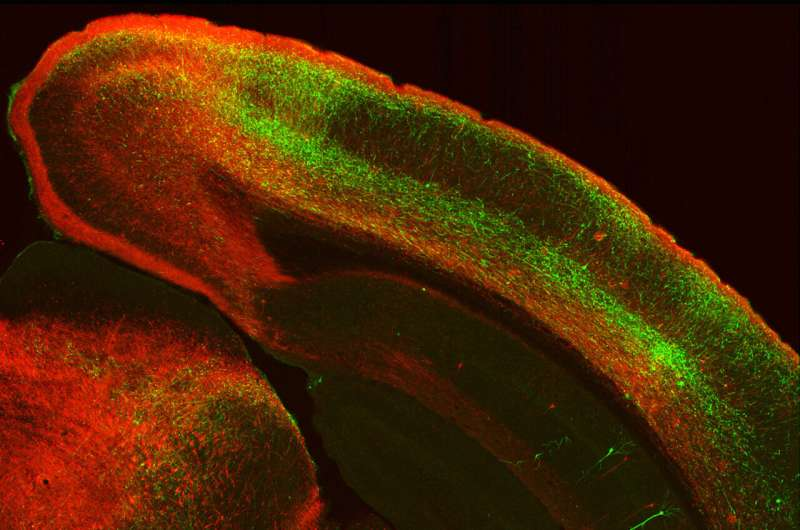

To map these circuits, researchers used detailed anatomical tracing techniques to show precisely where ACA and ORB axons travel. Both subregions innervate VISp and MOp, but they do so using distinct projection patterns and target different cortical layers:

- In VISp, ACA projects primarily to layer 6.

- ORB, on the other hand, targets layer 5.

These differences matter because each cortical layer has unique roles in processing and transmitting information.

The mice in the experiments:

- Ran freely on a wheel or remained still.

- Viewed structured images and naturalistic movies presented at multiple contrast levels.

- Were sometimes exposed to air puffs to artificially increase arousal.

During these tasks, researchers monitored activity in all four regions—ACA, ORB, VISp, and MOp—paying special attention to information flow in the axons coming from the PFC. They also selectively blocked ACA→VISp and ORB→VISp circuits to determine how VISp’s visual encoding changed.

The results showed:

- Blocking ACA feedback reduced VISp’s ability to sharpen visual representations when arousal increased.

- Blocking ORB feedback changed VISp encoding in the opposite direction, disrupting the system that normally reduces unimportant visual information during high arousal.

This demonstrated clear, functional specificity in how these circuits operate.

What the PFC Tells the Motor Cortex

The study didn’t focus only on visual processing. It also examined how the PFC talks to the primary motor cortex (MOp).

Both ACA and ORB:

- Convey information about running speed to MOp.

- Indicate whether the mouse is moving or still.

- Also deliver some arousal-related signals, along with a minor amount of visual information.

Interestingly, the PFC does not send detailed visual information to MOp the way it does to VISp. Instead, it gives MOp a broad contextual picture: how fast the animal is moving, whether it is aroused, and minimal cues related to what is being seen. This helps the motor system adjust behavior according to internal state and sensory environment without overwhelming it with unnecessary detail.

Why These Findings Matter

The implications of this research are much broader than the specific circuits in mouse brains.

Here’s why this work is important:

- It shows that top-down modulation from the PFC is highly specialized, not uniform.

- It demonstrates that perception is not just a passive reception of sensory data but a dynamic process influenced by internal states and feedback.

- It provides a mechanistic explanation for how arousal and movement directly influence the way visual information is encoded.

- It suggests that different PFC subregions may have distinct roles in disorders involving attention, perception, or executive control—such as ADHD, schizophrenia, and anxiety disorders.

The traditional view of vision is that sensory information flows forward—from the eyes to the thalamus to the visual cortex. But this research reinforces a more modern view: sensory processing is an active conversation, not a one-way street. Higher brain areas constantly reach back to adjust how incoming information is interpreted.

Additional Background: What the PFC Actually Does

Since this research heavily involves the prefrontal cortex, it’s useful to understand the broader context of what the PFC contributes across species.

The prefrontal cortex is crucial for:

- Decision-making

- Attention

- Evaluating outcomes

- Behavioral planning

- Integrating internal states with external cues

In many mammals, including humans, the PFC acts as a command center that integrates memory, emotion, and sensory information to guide behavior. What this study adds is a clearer understanding of how these roles manifest at the circuit level.

For example:

- The ACA is often linked to attention, action monitoring, and conflict processing.

- The ORB is tied to evaluating reward, value, and expectations.

This aligns neatly with the findings:

- ACA strengthens visual input when the animal needs to detect uncertain or faint stimuli.

- ORB suppresses overly strong or irrelevant input when arousal spikes, preventing distraction or sensory flooding.

Such balancing mechanisms could be evolutionarily advantageous: they help animals focus on weak, important signals (like predators or prey) while ignoring strong but irrelevant ones (like sudden noises that don’t pose a threat).

Additional Background: Why Arousal Matters in Brain Processing

Arousal isn’t just “feeling awake.” Neurologically, it includes physiological markers such as:

- Heart rate changes

- Pupil dilation

- Neuromodulatory activity (especially noradrenaline and acetylcholine)

As arousal increases:

- The brain becomes more sensitive to specific sensory features.

- Neural gain changes, which can either sharpen or overwhelm sensory representations.

This makes the discovery of subregion-specific PFC modulation even more compelling. It suggests that the brain uses multiple feedback channels to calibrate perception based on state, ensuring neither overload nor suppression.

Final Thoughts

This study gives one of the clearest demonstrations to date that the prefrontal cortex does not simply modulate sensory and motor regions in a global or uniform way. Instead, it deploys specialized, target-specific feedback circuits that shape perception and action depending on arousal, movement, and the demands of the moment. The work opens the door for future studies examining how similar mechanisms operate in humans and how disruptions in these pathways might contribute to neurological or psychiatric conditions.

Research Reference:

https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(25)00844-X