Hypertension Causes Early Brain Changes Long Before Blood Pressure Rises

Hypertension is widely known as a major cardiovascular problem, but new research suggests it may begin affecting the brain far earlier than most people realize—even before blood pressure noticeably increases. A new preclinical study from Weill Cornell Medicine offers one of the most detailed looks yet into how hypertension quietly disrupts the brain at the molecular and cellular levels. These early changes could help explain why people with chronic high blood pressure face a 1.2 to 1.5 times higher risk of developing cognitive disorders such as vascular cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

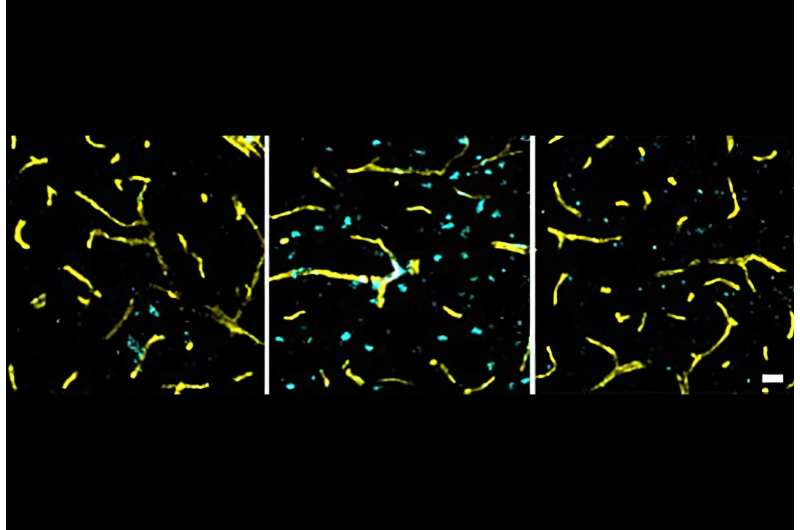

This new study, published on November 14, 2025 in the journal Neuron, mapped out how hypertension alters essential brain cells within just three days of onset—well before any measurable rise in blood pressure. The findings not only highlight the hidden neurological impact of hypertension but also point toward potential treatments that may protect both cardiovascular and cognitive health.

Hypertension Damages the Brain Before Blood Pressure Changes

Researchers used mice to examine early molecular changes triggered by hypertension. To mimic what happens in humans, they administered angiotensin, a hormone known to raise blood pressure. This is a well-established experimental model that gradually induces hypertension in a controlled and measurable way.

What surprised the scientists most was how quickly the brain reacted. After only three days of angiotensin exposure—before the mice developed high blood pressure—researchers observed major gene expression shifts in three crucial cell types:

- Endothelial cells

- Interneurons

- Oligodendrocytes

These are key components for maintaining blood flow, regulating neural signaling, and supporting myelin—the protective sheath that lets neurons communicate efficiently.

The early appearance of damage suggests hypertension is not just a condition of elevated pressure. There seems to be a biological cascade that begins earlier and independently affects the brain’s functional integrity.

Early Endothelial Cell Aging and a Weakened Blood-Brain Barrier

One of the most striking early findings involved endothelial cells, which line the inside of every blood vessel. Within three days, these cells showed signs of premature aging, including:

- Reduced energy metabolism

- Increased markers of cellular senescence

- Functional decline normally seen much later in disease progression

Aging of endothelial cells matters because they play a central role in maintaining the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB regulates which nutrients enter the brain and keeps harmful substances out.

In this study, researchers saw early indicators that the BBB was beginning to weaken. A compromised BBB can allow toxins, pathogens, and inflammatory molecules into brain tissue—something that is associated with cognitive decline and neurodegenerative conditions.

This weakening happening so early suggests hypertension may prime the brain for long-term damage long before symptoms appear.

Interneuron Disruption and Imbalanced Brain Activity

Interneurons are the “balancers” of the nervous system. They help regulate the mix of excitatory and inhibitory signals that keep neural networks stable.

At the three-day mark, these interneurons already showed signs of damage and dysfunction. The gene expression patterns resembled the irregularities often observed in brains with Alzheimer’s disease, where an imbalance in excitation and inhibition contributes to memory loss and confusion.

This means hypertension may directly disturb the delicate network activity required for thinking, learning, and memory.

Oligodendrocyte Dysfunction and Threatened Myelin Integrity

Oligodendrocytes are responsible for maintaining myelin, the fatty sheath that acts like insulation around nerve fibers. Healthy myelin ensures fast and efficient communication between neurons.

After only a few days of hypertension induction:

- Oligodendrocytes showed disrupted expression of genes tied to myelin maintenance

- Their ability to replace or repair myelin was impaired

- These changes set the stage for later communication problems between neurons

If myelin deteriorates, cognitive function eventually suffers because neurons simply cannot pass signals effectively.

By day 42, when blood pressure had fully risen in the mice, researchers found an even greater number of disrupted genes. This later stage corresponded to measurable declines in cognition—connecting the early molecular changes to real-world functional deficits.

Why These Findings Matter

People often think of hypertension as a numbers game—high pressure equals risk. But this study suggests the biology is more complex. The brain may be affected before traditional diagnostic thresholds are met.

This could explain several long-standing clinical puzzles:

- Many hypertension drugs lower blood pressure but do not improve cognitive function.

- Cognitive damage often appears even in people whose hypertension is being managed.

- Some individuals develop cognitive decline despite only mild hypertension on early tests.

If hypertension begins harming the brain before it raises measurable pressure, then standard screenings may miss the earliest and possibly most preventable stages of neurological injury.

Possible Treatment Pathway: Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

The researchers tested whether an existing blood pressure drug could counteract these early changes. They chose losartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) widely prescribed for hypertension.

Their experiments showed that losartan:

- Reversed early dysfunction in endothelial cells

- Restored healthier behavior in interneurons

- Provided partial protection during the early phases of hypertension

This is important because some studies in humans have hinted that ARBs may be more protective for brain health than other blood-pressure-lowering drugs. The new findings offer a potential explanation: blocking angiotensin receptors might interrupt the early damaging effects on the brain before high blood pressure appears.

However, the researchers stress that this study was conducted in mice. It remains to be tested how directly the results apply to humans.

What This Means for Understanding Hypertension

Although the study is preclinical, it supports a growing scientific view that hypertension is not only a cardiovascular condition but also a neurological one. The findings reinforce several ideas:

- Early detection of hypertension is crucial for long-term brain health.

- Even slight increases in vascular stress may have neurological consequences.

- A weakened BBB, interneuron damage, and impaired myelin maintenance are likely contributors to hypertension-related cognitive decline.

- Medications that target angiotensin signaling may offer dual protective effects.

Understanding these early processes may eventually lead to better diagnostic tools and treatments that target not just blood pressure but the underlying biological triggers that silently harm the brain.

Additional Background: How Hypertension Affects Brain Health in General

To give a broader context beyond the study, here are some known effects of chronic high blood pressure on the brain:

Reduced Blood Flow

Hypertension narrows and stiffens blood vessels, restricting blood flow to critical brain regions.

Increased Inflammation

Persistent vascular stress can trigger inflammation that breaks down neural tissue over time.

Microvascular Damage

Tiny vessels deep within the brain can rupture or clog, contributing to silent strokes and white matter lesions.

Higher Dementia Risk

Long-term studies show a consistent link between high blood pressure in midlife and later development of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

This new research strengthens the argument that these risks may begin building up far earlier than previously understood.

Research Paper:

Hypertension-Induced Neurovascular and Cognitive Dysfunction at Single-Cell Resolution

https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(25)00799-8