Immediate Treatment After Traumatic Brain Injury May Lower Long-Term Alzheimer’s Risk

New research from Case Western Reserve University is drawing attention to the importance of when a person receives treatment after a moderate or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). According to a large nationwide analysis, getting neurorehabilitation within the first seven days after a serious head injury may significantly cut down the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease years later. The findings are striking, especially considering how common TBIs are and how often their long-term effects go unnoticed.

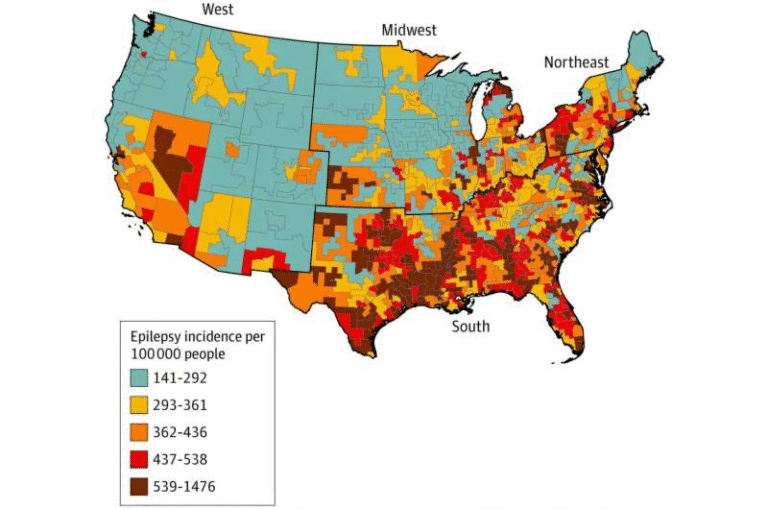

The study reviewed electronic health records from more than 100 million patients across various U.S. healthcare systems. From this massive dataset, researchers identified about 37,000 individuals aged 50 to 90 who had experienced a moderate or severe TBI. When comparing patients who received treatment within one week versus those who received delayed intervention, early treatment showed a 41% lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease at the three-year mark, and a 30% lower risk at five years. This difference is substantial and highlights that early medical action can have long-lasting protective benefits for the brain.

The research team—led by medical student Austin Kennemer, research assistant professor Zhenxiang Gao, and supervised by biomedical informatics expert Rong Xu—focused specifically on the timing of neurorehabilitation. Neurorehabilitation includes therapies designed to help the brain recover, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, cognitive rehabilitation, and speech-language therapy. These approaches take advantage of the brain’s ability to reorganize and form new neural connections at any age, whether someone is 5 years old or 95.

What makes these results compelling is that TBI has long been recognized as a major public health issue. An estimated 2.8 million Americans face traumatic brain injuries every year, and globally the number reaches around 69 million annually. TBIs are often called a silent epidemic because their long-term consequences—like chronic inflammation, cognitive decline, and increased dementia risk—may not show up until years after the injury.

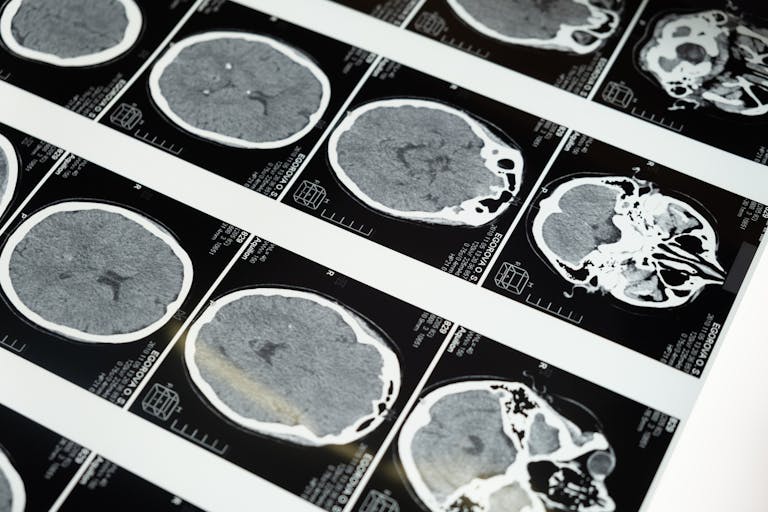

For decades, scientists have known that moderate and severe TBIs raise the likelihood of developing various neurodegenerative conditions. The biological reasons are complex. A hard blow or jolt to the head can lead to diffuse axonal injury, persistent inflammation, and damage to essential brain pathways. Over time, these disruptions can make the brain more vulnerable to developing conditions such as Alzheimer’s, which involves the accumulation of harmful proteins like beta-amyloid and tau. While not every person with a TBI develops Alzheimer’s, the risk is clearly higher, and scientists have been trying to determine what factors might help reduce that risk.

This new study offers one of the clearest signals yet that early intervention matters. It suggests that getting neurorehabilitation started within a week may interrupt or slow the harmful processes set in motion by a TBI. When the brain is injured, inflammation and cell damage begin quickly. Early rehabilitation may help preserve neural pathways, support recovery, and prevent the kind of long-term deterioration associated with Alzheimer’s.

The study’s findings also align with earlier research from the National Institutes of Health, which showed that patients who receive neurorehabilitation during hospitalization for brain injuries leave the hospital with higher cognitive function than those who do not receive such treatments. The new research builds on this by evaluating not just short-term recovery, but the long-term risk of a specific neurodegenerative disease.

Beyond Alzheimer’s, the team behind the study is already expanding their work. They are looking at how rehabilitation timing after TBI might influence the risk of other neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease. Given the millions of people affected by traumatic brain injuries—ranging from athletes and accident victims to military personnel—understanding how timing affects long-term brain health could have major public health implications.

Understanding Traumatic Brain Injury More Deeply

To better appreciate the significance of the new findings, it helps to understand how TBIs work and why they’re so harmful.

A traumatic brain injury occurs when the brain is damaged by an external force. This could happen in a car accident, a fall, a sports collision, or a combat situation. TBIs range from mild (commonly known as concussions) to severe, where the brain may experience bleeding, swelling, or significant tissue damage.

Moderate to severe TBIs pose a greater risk of long-term consequences because the injury affects deeper structures of the brain. After the initial mechanical impact, a secondary wave of injury often unfolds. This includes inflammation, reduced blood flow, disrupted cell signaling, and oxidative stress. Over time, these processes can impair memory, attention, mood, and behavior—sometimes permanently.

One of the reasons TBIs are so challenging is that symptoms don’t always appear immediately. Someone may feel fine following an accident, only for cognitive issues to emerge months or even years later. This is partly why experts call TBIs a silent epidemic: the effects are widespread but often overlooked.

Why Early Neurorehabilitation Helps

The brain has an incredible ability known as neuroplasticity—the capability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections. Neurorehabilitation leverages this ability. By engaging patients in guided physical and cognitive activities, therapy stimulates areas of the brain that may have been weakened or disrupted.

Starting rehabilitation early offers several benefits:

- It helps maintain healthy neural pathways before damage becomes permanent.

- It reduces the intensity of chronic inflammation.

- It encourages the brain to “rewire” itself more effectively.

- It supports physical recovery, helping patients regain independence sooner.

According to the new study, the timing of these therapies plays a critical role. Intervening within the first week seems to have a protective effect that extends far beyond the typical recovery period.

Implications for Healthcare and Policy

If early neurorehabilitation truly reduces Alzheimer’s risk by as much as 41%, emergency departments and hospitals may need to reconsider how quickly they refer TBI patients to rehabilitation services. Right now, access to neurorehabilitation varies widely depending on hospital resources, insurance coverage, and patient awareness.

Improving access to timely rehabilitation could significantly improve long-term outcomes for millions of people. It may even lower healthcare costs by reducing the number of dementia cases developing years later.

The research team hopes their findings will encourage healthcare systems to adopt earlier and more consistent neurorehabilitation practices. They also emphasize the need for further studies to confirm the results and explore related questions.

Final Thoughts

Traumatic brain injury is a major global health concern, and its long-term impact on cognitive decline has been a subject of research for decades. This new study offers a hopeful message: acting quickly after a TBI could make a real difference in protecting brain health for years to come. While more research is needed, the evidence so far suggests that early neurorehabilitation may be one of the most effective tools available for reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease after a serious head injury.

Research Paper:

Timing of Neurorehabilitation and Subsequent Alzheimer’s Disease Risk in Patients With Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1177/13872877251385262