Immune System Activity May Be Driving Brain Damage After Repeated Concussions, New Study Suggests

Repeated concussions, whether sustained on football fields, soccer pitches, or military training grounds, have long been linked to lasting brain problems. These injuries are associated with mood disorders, memory decline, movement difficulties, and serious long-term conditions such as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a disease that has affected several former professional athletes. While the risks are well known, the precise biological mechanisms behind this damage have remained unclear.

A new study now points to a surprising contributor: the body’s own immune system. Researchers have found that immune responses meant to protect the body may actually worsen brain damage after repeated mild concussions.

The research was led by Stephen Tomlinson, Ph.D., a professor of Pharmacology and Immunology at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), along with Silvia Guglietta, Ph.D., an associate professor of Regenerative Medicine and Cell Biology. Their team included Khalil Mallah, Ph.D., the study’s first author and assistant professor of Pharmacology and Immunology, Carsten Krieg, Ph.D., assistant professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and other collaborators. The findings were published in the journal Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy in 2025.

At the center of the study is a powerful part of the immune system called the complement system. This system consists of more than 50 different proteins that help the body fight infections. It works by tagging harmful invaders like bacteria and viruses and triggering inflammation to help eliminate them. While this process is essential for survival, it can become harmful when it is activated too strongly or for too long—especially in the brain.

Scientists already knew that complement activation plays a role in severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke. However, its role in repeated mild concussions, which are far more common in sports and military settings, had not been studied in depth. This research set out to fill that gap.

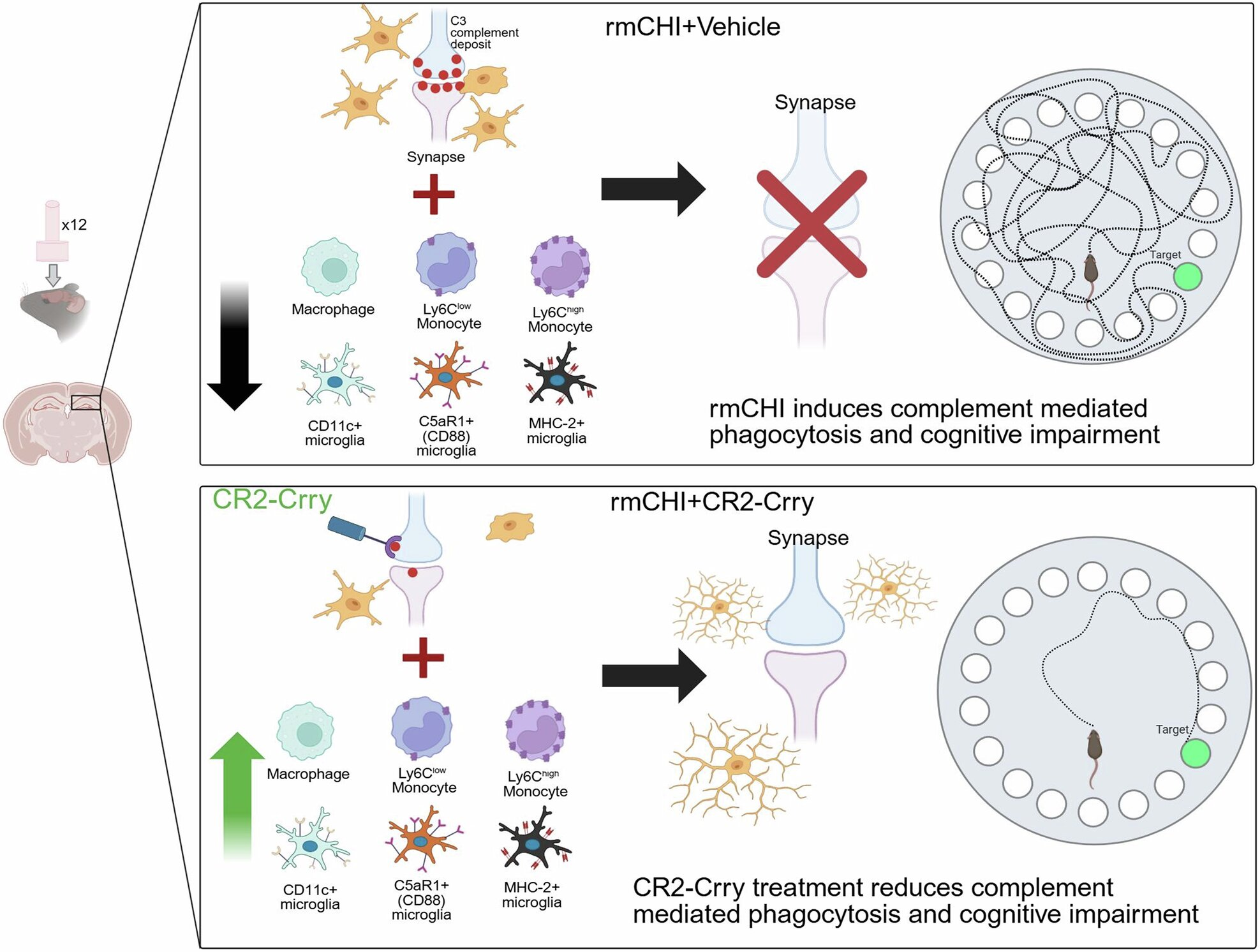

One of the most important aspects of the study was the creation of a new experimental model. The researchers developed a murine (mouse) model designed specifically to mimic repetitive mild closed head injury, closely resembling how humans experience multiple concussions over time. Most previous studies focused on single, severe brain injuries, leaving a major gap in understanding how repeated low-level impacts affect the brain.

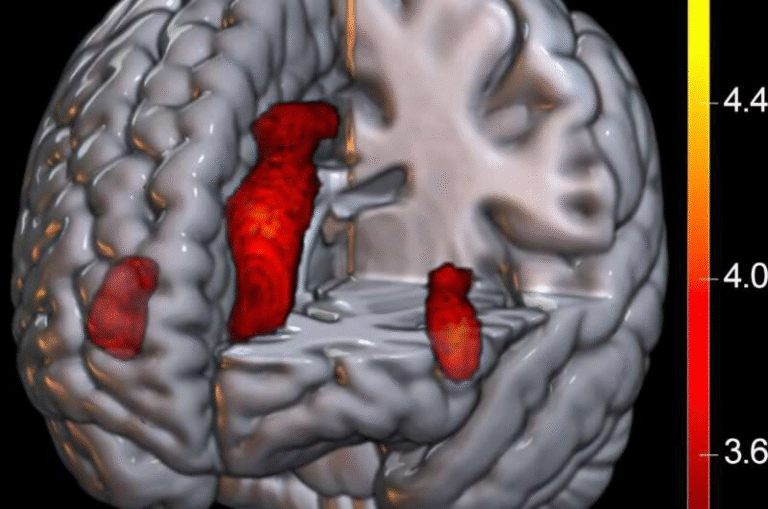

Using this model, the team observed what happens in the brain after repeated concussions. They found that these injuries trigger sustained activation of the complement system, which in turn affects microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells.

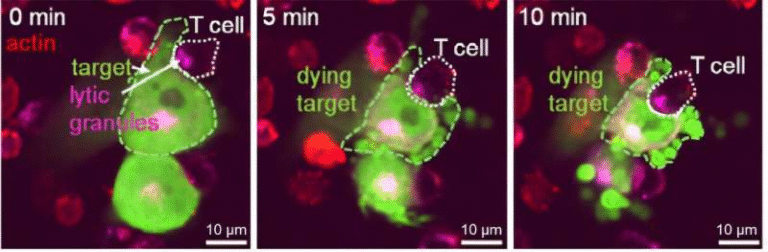

Microglia act as the brain’s cleanup crew. After injury, they remove dead or damaged cells through a process called phagocytosis, which is critical for healing. Under normal conditions, this response is protective. But the study found that after repeated concussions, complement activation pushes microglia into an overactive state.

When microglia become too aggressive, they do not limit themselves to clearing debris. Instead, they may begin removing weakened but still living neurons and synapses. Synapses are the connections between neurons that allow brain cells to communicate. Losing them can seriously disrupt brain function, leading to cognitive problems that persist long after the initial injury.

To test whether this immune overreaction was driving the damage, the researchers used an experimental drug called CR2-Crry, a targeted complement inhibitor. This compound works by blocking complement activation specifically at sites of injury, rather than shutting down the immune system entirely.

The results were striking. When complement activity was inhibited, microglia became less aggressive, and the brain showed clear signs of protection. Synapses and neurons were better preserved, inflammation levels in the brain returned closer to normal, and injured cells had a greater chance of recovery. Most importantly, the test subjects showed reduced cognitive impairments compared to those that did not receive the inhibitor.

These findings strongly suggest that complement-driven inflammation is a major cause of ongoing brain damage after repeated concussions. Rather than being a secondary effect, immune system activity appears to play a central role in shaping long-term outcomes.

This research has significant implications for public health. Contact sports such as football, soccer, hockey, and boxing expose athletes to repeated head impacts, often starting at very young ages. Military personnel face similar risks during training and combat. The idea that even mild concussions can trigger long-lasting immune-driven damage highlights the importance of better prevention and treatment strategies.

Currently, treatments for traumatic brain injury focus mainly on managing symptoms rather than addressing the underlying biological processes. There are no approved therapies that specifically target the chronic inflammation that can follow a concussion. However, this study offers hope. Complement inhibitors similar to CR2-Crry are already being tested for other diseases, which could make it easier to adapt them for brain injury treatment in the future.

It is also important to note that complement proteins are not inherently harmful. They play essential roles in normal brain development and function, including shaping neural circuits. This makes understanding their behavior after injury especially important. The goal is not to eliminate complement activity altogether, but to control it carefully so it does not cross the line from helpful to harmful.

The study focused on short-term and subacute outcomes after repeated concussions. The research team is now continuing to monitor their experimental subjects over longer periods to determine whether early complement inhibition can prevent long-term neurodegeneration and conditions similar to CTE.

Beyond this specific study, the findings add to a growing body of evidence showing that neuroinflammation plays a critical role in brain injury. After trauma, the brain’s immune response can remain active for months or even years, potentially driving progressive damage. Understanding how to regulate this response may be key to protecting brain health after injury.

In simple terms, this research suggests that the brain’s biggest enemy after repeated concussions may not be the impact itself, but the immune response that follows. By identifying a specific pathway—the complement system—that drives lasting damage, scientists have opened the door to new therapeutic strategies that could one day help athletes, service members, and others at risk of repeated head injuries.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-025-02466-7