Iron-Snatching Compounds Show Promise as a New Way to Fight Parasitic Flatworms

Researchers have uncovered a potential new strategy to fight schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease that affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide. A recent study led by a scientist at RIKEN, Japan’s largest comprehensive research institution, shows that a series of iron-snatching compounds can effectively block the growth and survival of Schistosoma parasites by depriving them of iron, a nutrient they critically depend on.

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed journal Tropical Medicine and Health, suggest a fresh approach to parasite control at a time when concerns about drug resistance are steadily growing.

Schistosomiasis and Why New Treatments Are Needed

Schistosomiasis is caused by parasitic flatworms belonging to the genus Schistosoma. The disease is transmitted when people come into contact with freshwater contaminated by larval forms of the parasite, often in regions with limited sanitation infrastructure.

Once inside the human body, the parasites mature and settle in blood vessels, where they can survive for years. The disease initially causes symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloody urine, but chronic infections are far more damaging. Over time, schistosomiasis can lead to severe liver, intestinal, bladder, and kidney damage, significantly reducing quality of life.

Globally, around 250 million people are estimated to be infected, and alarmingly, about half of them are children of school age, making schistosomiasis one of the most impactful neglected tropical diseases.

For decades, treatment has relied almost entirely on a single drug: praziquantel. Developed roughly 50 years ago, praziquantel is effective at killing adult worms, but it has several limitations. It does not work well against larval stages, and there is increasing concern that widespread use could eventually lead to drug-resistant parasites. These challenges have created an urgent need for new drugs with different modes of action.

Targeting a Weak Spot: The Parasite’s Need for Iron

The new study focuses on a surprisingly vulnerable point in the parasite’s biology: iron dependence.

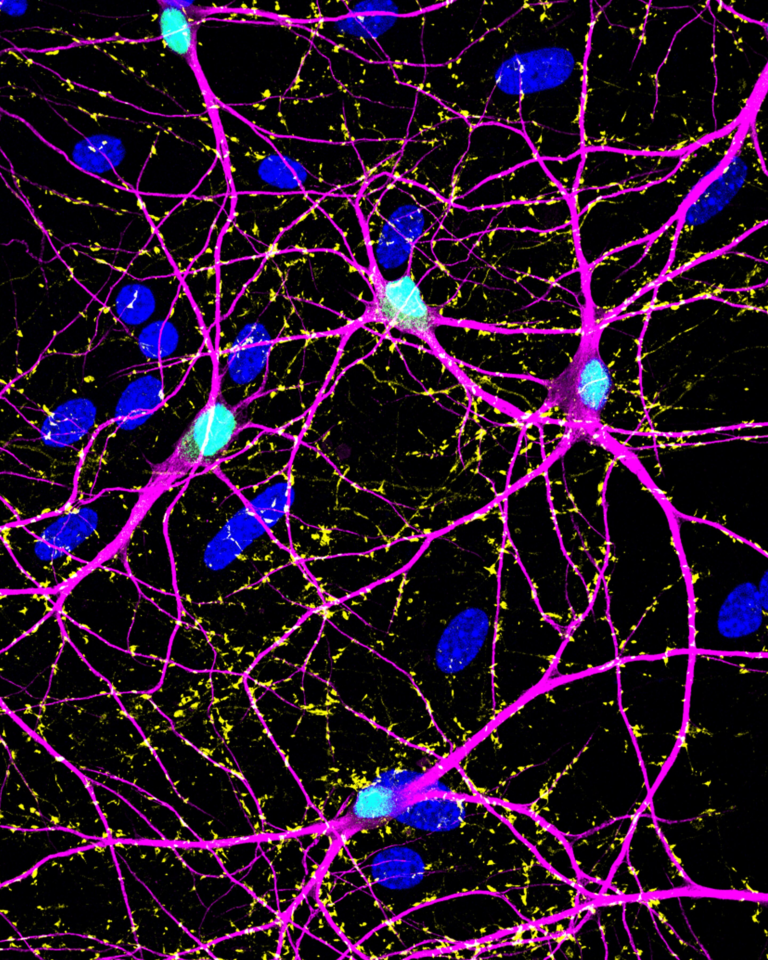

Iron is essential for nearly all living organisms, including parasites. It plays a central role in energy production, enzyme function, growth, differentiation, and reproduction. Many pathogens have evolved sophisticated systems to steal iron from their hosts, and Schistosoma parasites are no exception.

The research was led by Akira Wada from the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences, who has previously studied how iron deprivation affects other parasites. Earlier work from his group showed that metal-binding compounds capable of “snatching” iron could severely restrict the growth of malaria and amoebic parasites.

This raised a crucial question: could the same strategy work against Schistosoma?

Testing Iron-Snatching Compounds Against Schistosoma

To explore this idea, Wada and his collaborators tested a series of phenanthroline-based compounds, known for their strong metal-binding properties. These compounds are designed to tightly bind iron molecules, making the metal unavailable to parasites.

The researchers focused on multiple stages of the parasite’s life cycle, which is particularly important because praziquantel mainly targets adult worms. In laboratory experiments, the iron-snatching compounds were tested against schistosomula, the larval form of Schistosoma that develops after the parasite enters the human body.

The results were striking. Several of the compounds killed schistosomula more efficiently than praziquantel, highlighting their potential as next-generation antischistosomal agents. This is especially significant because targeting larval stages could help stop infections earlier and reduce long-term disease progression.

Effects on Adult Worms and Egg Production

The study did not stop at larval stages. The researchers also investigated how the compounds affected adult worms, particularly their ability to reproduce.

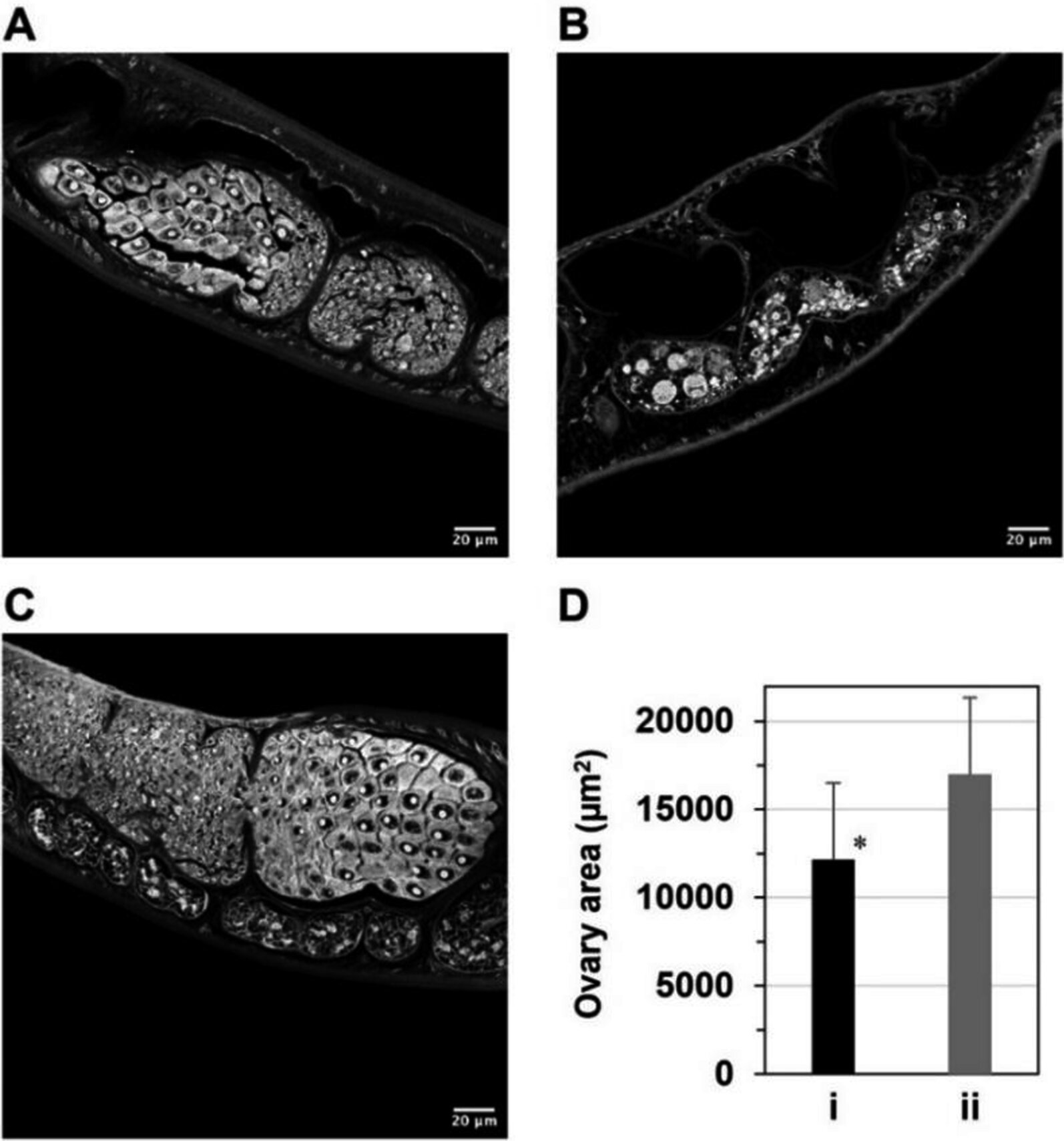

One compound in particular, known as PHN-(OMe)₂, showed notable effects in mouse models infected with Schistosoma mansoni, one of the main species responsible for human schistosomiasis. When administered orally to infected mice, PHN-(OMe)₂ caused a significant reduction in egg production by female worms.

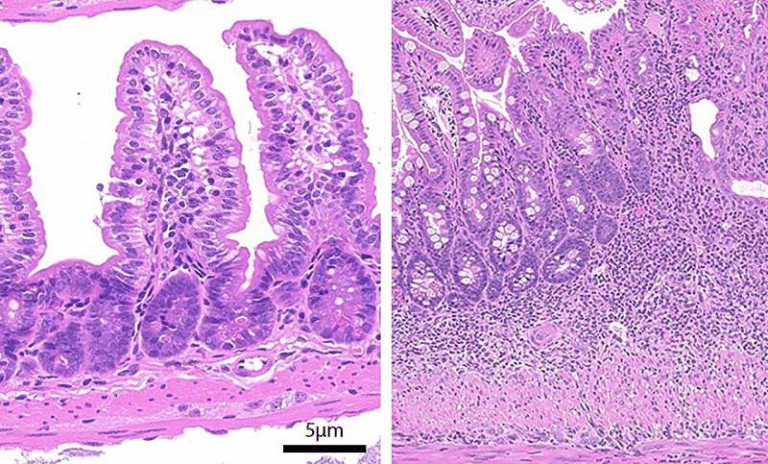

Microscopic analysis revealed that this reduction was linked to ovarian atrophy in the female parasites. In other words, depriving the worms of iron interfered with their reproductive organs, preventing normal egg-laying behavior. This is a critical finding because parasite eggs, rather than adult worms themselves, are responsible for much of the tissue damage and inflammation seen in schistosomiasis.

Images from the study showed clear differences between worms collected from mice treated with PHN-(OMe)₂ and those given olive oil as a control, with treated worms exhibiting visibly smaller ovarian areas.

Why Egg Suppression Matters

Reducing egg production is not just a bonus effect—it could be a major advantage in controlling schistosomiasis. Eggs become trapped in host tissues, triggering immune reactions that lead to scarring and organ damage. By suppressing egg production, iron-snatching compounds could potentially reduce both disease severity and transmission.

The study demonstrated that iron is essential not only for larval survival, but also for adult reproduction, reinforcing the idea that iron deprivation targets the parasite at multiple vulnerable stages.

A Broader Strategy for Parasitic Diseases

Beyond schistosomiasis, the findings point to a broader therapeutic strategy. Many pathogenic parasites rely on iron to survive and thrive inside their hosts. Interfering with iron acquisition could therefore be a generalizable approach for treating a range of parasitic infections.

The researchers emphasize that parasites have evolved specialized systems for iron uptake, and disrupting these systems may offer a way to selectively harm parasites without severely affecting the host.

Wada has expressed interest in expanding this line of research to other neglected tropical diseases, particularly those for which effective drug treatments are still lacking.

What Comes Next for Iron-Based Antiparasitic Drugs

While the results are promising, these compounds are still at an early research stage. Further studies will be needed to evaluate their safety, toxicity, optimal dosing, and long-term effectiveness. Researchers will also need to determine how well these compounds perform in larger animal models and, eventually, in human trials.

Nevertheless, the study provides strong proof of concept that iron deprivation can be an effective way to combat Schistosoma parasites, offering hope for more diverse and resilient treatment options in the future.

At a time when global health efforts are increasingly focused on neglected diseases, this research represents a fresh and scientifically grounded approach that could complement or even transform existing treatment strategies.

Research Reference:

Takashi Kumagai et al., Molecular containment of iron source inhibits larval survival of Schistosoma mansoni and egg-laying behavior of the female adult worms via ovarian atrophy, Tropical Medicine and Health (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-025-00800-x