Just 20 Minutes of Exercise Twice a Week May Help Slow Dementia, According to a New Long-Term Study

A growing body of research has long suggested that physical activity is good for brain health. Now, a new large-scale study offers a clearer answer to a question many older adults and caregivers often ask: how much exercise is actually needed to make a difference when it comes to slowing dementia?

According to researchers from the Texas A&M University School of Public Health, the answer may be surprisingly modest. The study found that as little as 20 minutes of physical activity, done twice a week, is associated with a reduced risk of progressing from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in older adults.

What the Study Looked At

The research was conducted by scientists from the Center for Community Health and Aging at Texas A&M and was published in the Journal of Physical Activity and Health in 2025. Instead of focusing on short-term experiments, the researchers took a longitudinal approach, meaning they followed people over several years to see how their activity levels related to changes in brain health.

To do this, they analyzed data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a well-established national study in the United States that surveys adults aged 50 and older every two years. The specific data used in this analysis spanned 2012 to 2020, giving the researchers nearly a decade of information to work with.

After applying selection criteria, the final sample included 9,714 participants. The median age of participants was 78 years, making this a particularly relevant study for older populations. About 68.6% of participants were male, while 31.4% were female. In terms of marital status, just over half were married, and around 42% were widowed or divorced.

During the study period, 8% of participants were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia.

Understanding Mild Cognitive Impairment

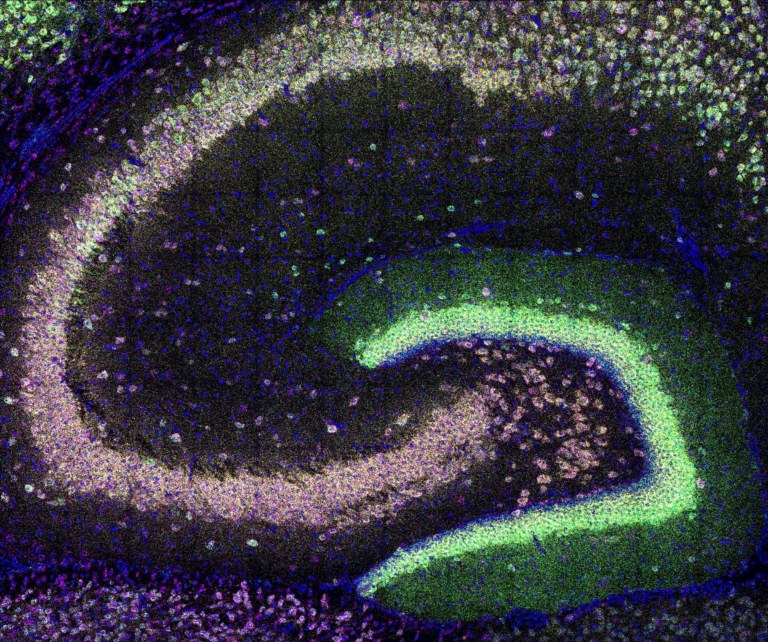

The study focused specifically on individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This condition involves noticeable declines in memory or thinking ability, but not severe enough to interfere with everyday life. Importantly, MCI is often considered a possible step on the path toward Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, though progression is not guaranteed.

Some people with MCI remain stable for years, some improve, and others do go on to develop dementia. This variability is what makes identifying protective factors—like physical activity—so important.

How Cognitive Function Was Measured

To assess cognitive status, researchers evaluated participants across three key areas of cognition:

- Memory, measured through immediate and delayed recall of a list of 10 spoken words

- Working memory, assessed by repeatedly subtracting seven from 100 over five trials

- Attention and processing speed, tested by counting backward from 20 to 10 over two trials

These standardized tests allowed researchers to track changes in cognitive function over time. Dementia outcomes were determined using self-reported medical diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias and any changes reported since the beginning of the study.

Measuring Physical Activity Levels

One of the strengths of this study is how detailed its activity data was. Researchers examined how often participants engaged in 21 different types of physical activities, ranging from more structured exercise to everyday movement such as walking.

They also analyzed both frequency and duration, allowing them to identify thresholds at which activity appeared to have meaningful benefits. What stood out was that participants who maintained moderate levels of physical activity—defined in this study as at least 20 minutes per session, twice a week—had a significantly lower risk of developing dementia over time.

In contrast, participants who were largely inactive saw little to no protective benefit.

Key Findings Beyond Exercise

While physical activity was a central focus, the study also examined other factors that influenced dementia risk. Several important patterns emerged:

- Age was strongly associated with higher dementia risk

- Higher levels of education were linked to lower risk

- Better baseline cognitive function reduced the likelihood of developing dementia

- Sex had no significant effect, meaning men and women benefited similarly

These findings align with what is already known about cognitive aging, reinforcing the idea that dementia risk is shaped by a combination of biological, social, and lifestyle factors.

Why Small Amounts of Exercise Matter

One of the most encouraging aspects of this research is how achievable the recommended activity level is. Many older adults, especially those with mobility challenges or early cognitive decline, find standard exercise guidelines intimidating. In contrast, 40 minutes of activity spread across a week feels far more realistic.

Simple activities like walking, light sports, or other moderate movements can be enough to support brain health. The study highlights that regular movement, rather than intense or prolonged workouts, is what appears to matter most.

How Exercise May Protect the Brain

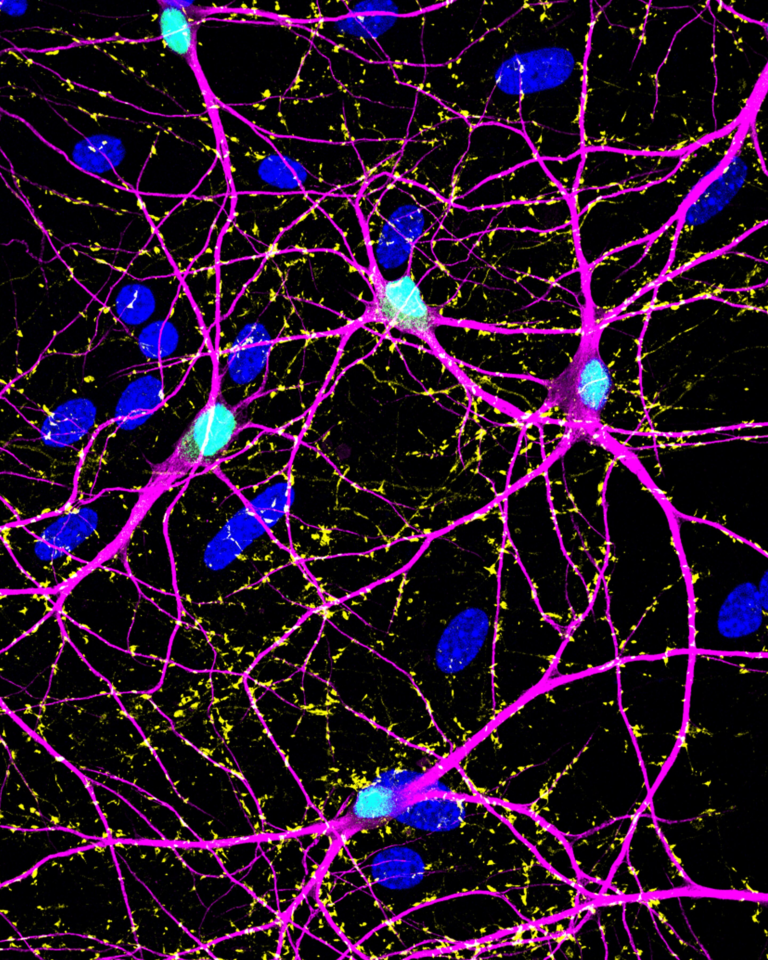

Although this study focused on outcomes rather than biological mechanisms, previous research offers clues about why physical activity may help. Exercise has been shown to:

- Improve blood flow to the brain

- Support the growth and maintenance of neural connections

- Reduce inflammation, which is linked to neurodegenerative diseases

- Improve cardiovascular and metabolic health, both of which are tied to cognitive function

Together, these effects may help slow the brain changes associated with dementia.

Limitations and Real-World Impact

Like all observational studies, this research has limitations. Physical activity levels were self-reported, which can introduce inaccuracies. The study also cannot prove that exercise directly prevents dementia—it shows a strong association, not direct causation.

Still, the large sample size, long follow-up period, and detailed analysis make the findings compelling. The researchers believe this information could be valuable for developing community-based programs aimed at older adults with mild cognitive impairment.

Notably, surveys suggest that one in nine U.S. adults aged 45 and older report worsening confusion or memory loss. As populations continue to age, low-cost and accessible strategies like physical activity may play a crucial role in public health efforts.

What This Means for Older Adults and Caregivers

For people concerned about cognitive decline, this study delivers a hopeful message: you don’t need to do a lot to gain benefits. Consistent, moderate activity—even in small doses—may help slow progression and support brain health.

It also reinforces the idea that lifestyle choices, alongside medical care, can make a meaningful difference in aging well.