Losing the Ability to Make Vitamin C May Protect Animals From a Deadly Parasitic Disease

Scientists have long believed that vitamin deficiencies are purely harmful. After all, vitamin C deficiency is famously linked to scurvy, a disease that once devastated sailors. But new research from Children’s Medical Center Research Institute (CRI) at UT Southwestern challenges this one-sided view. The study reveals something unexpected: losing the ability to synthesize vitamin C can actually protect animals from schistosomiasis, a widespread and often deadly parasitic disease.

This discovery not only reshapes how scientists think about vitamins but also raises intriguing questions about human evolution, parasite biology, and disease resistance.

Vitamin C, GULO, and an Evolutionary Puzzle

Most animals do not need to get vitamin C from food because they can make it themselves. They rely on a gene called L-Gulonolactone Oxidase (GULO), which enables the final step of vitamin C synthesis inside the body. Humans, however, lack a functional GULO gene. So do some other animals, including guinea pigs, certain bats, and some birds and fish.

Because of this genetic loss, vitamin C became a dietary necessity for humans rather than a compound we can produce internally. For decades, scientists assumed this loss was evolutionarily neutral—neither helpful nor harmful—because no clear advantage had ever been identified. The new CRI study turns that assumption on its head.

Schistosomiasis: A Global Health Burden

The disease at the center of this research is schistosomiasis, caused by parasitic flatworms called schistosomes. These parasites infect people when their larvae penetrate the skin during contact with contaminated freshwater. Once inside the body, schistosomes settle in blood vessels near the liver, where they can survive for decades.

Schistosomiasis affects nearly 250 million people worldwide, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions. The disease causes chronic inflammation, liver damage, anemia, growth problems in children, and in severe cases, death. Much of the damage comes not from the adult worms themselves but from the eggs they produce, which trigger intense immune reactions.

Why Vitamin C Matters to Schistosomes

A key insight behind this study comes from earlier research showing that schistosomes cannot synthesize vitamin C on their own. Like humans, they rely entirely on external sources. In 2019, scientists demonstrated that schistosomes require vitamin C to lay eggs in laboratory conditions.

This raised a crucial question: What happens if the host doesn’t have enough vitamin C to spare?

The Mouse Experiments That Changed Everything

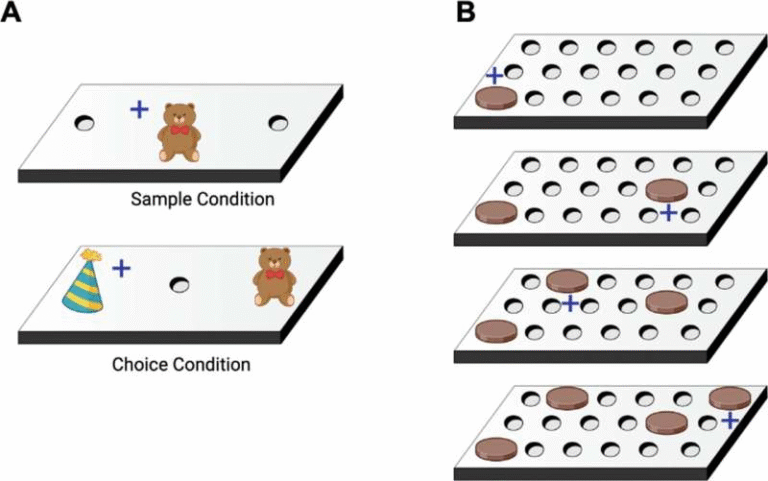

To test this idea, researchers led by Dr. Michalis Agathocleous, Assistant Professor at CRI and UT Southwestern, compared two groups of mice:

- Normal mice, which can naturally synthesize vitamin C

- Gulo-deficient mice, genetically engineered to lack the GULO gene and therefore unable to produce vitamin C

Both groups were infected with schistosomes.

The results were striking. Most normal mice developed severe schistosomiasis and died from the infection. In contrast, only about 5% of the Gulo-deficient mice died, despite being infected with the same parasites. These vitamin C–deficient mice showed dramatically reduced disease severity.

Even more interesting, when the researchers gave the Gulo-deficient mice intermittent vitamin C supplementation, the animals avoided scurvy while still retaining protection against severe schistosomiasis. This showed that temporary or partial vitamin C deficiency was enough to disrupt the parasite’s life cycle without causing catastrophic harm to the host.

How Vitamin C Deficiency Disrupts the Parasite

The protective effect comes down to timing and biological priorities. Schistosomes need vitamin C constantly to support egg production, which occurs daily. The host, on the other hand, takes months to develop serious illness from vitamin C deficiency.

As a result, a host that is temporarily low in vitamin C can survive long enough to starve the parasite of a critical resource, sharply reducing egg production. Fewer eggs mean less tissue damage, lower inflammation, and improved survival.

In essence, vitamin C deficiency creates an environment where the parasite suffers before the host does.

Rethinking Vitamins and Their Role in Disease

This research challenges the traditional idea that vitamins are always beneficial and deficiencies are always harmful. Instead, it shows that the relationship between nutrition and disease is deeply context-dependent.

The findings also echo earlier work by Dr. Agathocleous, who discovered in 2017 that vitamin C deficiency can promote the development of myeloid leukemia, a blood cancer affecting bone marrow and white blood cells. Together, these studies highlight that vitamin C can play very different roles depending on the disease and biological context.

Could This Explain Why Humans Lost GULO?

One of the most fascinating implications of this study is its relevance to human evolution. Schistosomiasis has plagued humans for thousands of years and remains extremely common today. If ancestral primates lived in environments where schistosome infections were widespread, losing the ability to synthesize vitamin C might have provided a survival advantage under certain conditions.

The researchers are careful to emphasize that they cannot prove this evolutionary scenario. Testing for positive selection on a gene lost millions of years ago is extremely difficult. However, the strength of the survival benefit observed in infected animals makes the idea biologically plausible.

Important Caveats and Human Health Implications

Despite how intriguing these findings are, the researchers stress that this is not a recommendation for humans to avoid vitamin C. Prolonged deficiency causes serious health problems, including scurvy, immune dysfunction, and impaired wound healing.

Instead, the study opens doors to new therapeutic strategies. Rather than depriving people of vitamin C, scientists could look for ways to block parasites from accessing or using vitamin C within the body. Such approaches could weaken parasites without harming the host.

Why This Research Matters

This work highlights a broader principle in biology: what benefits a host may harm a parasite, and vice versa. It also shows that traits long assumed to be useless or neutral may hold hidden advantages when viewed through the lens of infectious disease.

By challenging conventional wisdom about vitamins, this study encourages scientists to think more critically about nutrition, evolution, and host–pathogen interactions. It also underscores how deeply interconnected metabolism and disease truly are.

What Comes Next

The Agathocleous Lab plans to continue exploring how vitamin C and its deficiency influence human diseases, including parasitic infections and blood cancers. Future research may uncover new ways to exploit parasite-specific nutritional needs, potentially leading to safer and more effective treatments for diseases like schistosomiasis.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2517730122