MIT Researchers Reprogram Liver Cells to Restore T Cell Function in Aging Immune Systems

As people grow older, their immune systems gradually lose strength. One of the most noticeable changes is a steady decline in T cells, a type of white blood cell that plays a central role in fighting infections, responding to vaccines, and targeting cancer cells. With age, T cell numbers shrink, their diversity decreases, and their response time slows down. This is a major reason older adults are more vulnerable to infections and often respond less effectively to vaccines and immunotherapies.

Now, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have reported a striking new strategy to counter this decline. Instead of trying to directly repair the aging immune system, they found a way to temporarily reprogram liver cells so they can support T cell development and function. In animal studies, this approach significantly rejuvenated immune responses in older mice, improving both vaccine effectiveness and cancer immunotherapy outcomes.

Why the Immune System Declines With Age

A key driver of immune aging is the gradual breakdown of the thymus, a small organ located just above the heart. The thymus is where immature T cells mature and undergo quality control checks that ensure they can recognize a wide range of pathogens while avoiding damage to the body’s own tissues. It also releases signaling molecules that help T cells survive and function properly.

Unfortunately, the thymus starts shrinking surprisingly early in life. This process, known as thymic involution, begins in early adulthood and accelerates with age. By around the age of 75, the thymus is largely nonfunctional, producing very few new T cells. As a result, the immune system becomes increasingly dependent on older, less adaptable T cells that were generated earlier in life.

Previous attempts to address this problem have focused on injecting immune growth factors directly into the bloodstream or attempting to regrow thymic tissue using stem cells. While promising in theory, these strategies can come with serious side effects or face major technical challenges.

A Synthetic Alternative to the Thymus

The MIT research team took a very different approach. Instead of fixing or replacing the thymus itself, they asked whether the body could be engineered to mimic some of the thymus’s key functions elsewhere.

Their solution was to create a temporary biological “factory” inside the body that could produce the same signals the thymus normally provides. For this factory, they chose the liver, and for good reason.

The liver is exceptionally good at producing proteins, even in old age. It is also one of the easiest organs to target with mRNA-based therapies, because many injected nanoparticles naturally accumulate there. Just as importantly, all circulating blood passes through the liver, including immune cells, making it an ideal hub for delivering immune-supporting signals throughout the body.

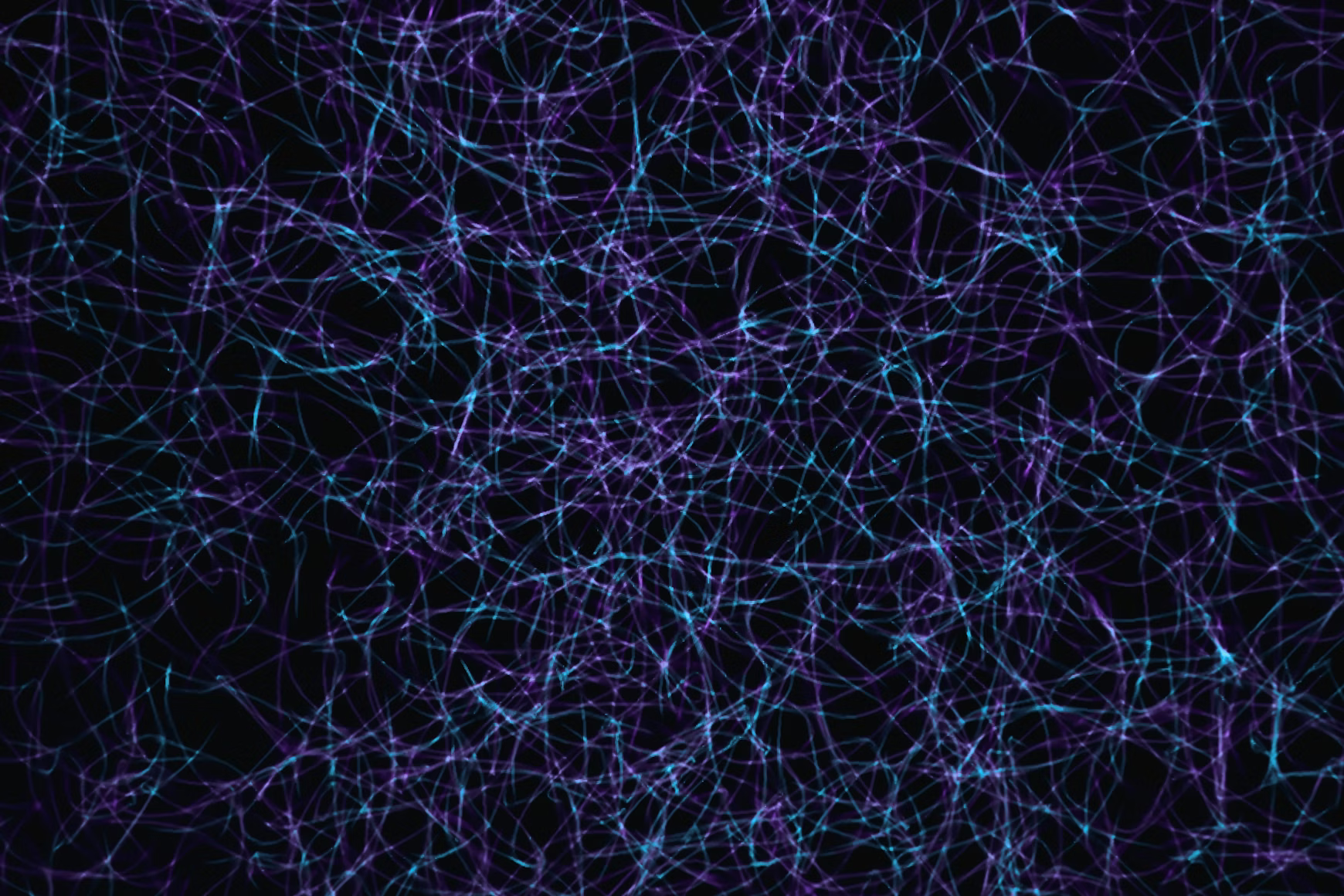

Using mRNA to Deliver Critical Immune Signals

To build this temporary immune factory, the researchers identified three key factors that are essential for T cell maturation and survival:

- DLL1, a protein involved in Notch signaling, which is crucial for early T cell development

- FLT-3 ligand, which supports the growth of immune progenitor cells

- IL-7 (Interleukin-7), a cytokine that plays a central role in T cell survival and expansion

The team encoded these three factors into mRNA molecules and packaged them into lipid nanoparticles, similar to those used in mRNA vaccines. When injected into the bloodstream, these nanoparticles traveled to the liver, where hepatocytes absorbed the mRNA and began producing the encoded proteins.

Because mRNA is naturally short-lived, the effect is temporary. This is a deliberate design feature, as it allows the immune boost to be tightly controlled and reduces the risk of long-term side effects from overstimulating the immune system.

Testing the Approach in Aging Mice

To see whether this strategy could truly rejuvenate the immune system, the researchers tested it in 18-month-old mice, roughly equivalent to humans in their 50s. To maintain steady production of the immune-supporting factors, the mice received multiple injections over a four-week period.

The results were clear and consistent. After treatment, the mice showed significant increases in T cell numbers, along with improved functional capacity. The diversity of their T cell populations also increased, which is essential for recognizing a wide range of pathogens.

Stronger Responses to Vaccines

The team next examined whether the rejuvenated immune systems could respond better to vaccination. They immunized the mice with ovalbumin, a protein commonly used in laboratory studies to track antigen-specific immune responses.

In treated mice, the number of cytotoxic T cells specifically targeting ovalbumin doubled compared to untreated mice of the same age. This finding is particularly important because reduced vaccine effectiveness is a major concern in older populations, as seen with influenza, COVID-19, and other infectious diseases.

Improved Cancer Immunotherapy Outcomes

The researchers also explored whether the treatment could enhance responses to cancer immunotherapy, which often relies on a robust T cell population to be effective.

In this experiment, aged mice were first treated with the mRNA therapy, then implanted with tumors and given a checkpoint inhibitor drug targeting PD-L1. Checkpoint inhibitors are designed to remove the molecular “brakes” that prevent T cells from attacking cancer cells, but they are often less effective in older patients.

Mice that received both the checkpoint inhibitor and the liver-targeted mRNA treatment showed much higher survival rates and longer lifespans than mice that received immunotherapy alone. This suggests that boosting T cell production and health can dramatically improve the effectiveness of existing cancer treatments.

Why All Three Factors Matter

An important finding from the study is that all three delivered factors were necessary to achieve the full immune-enhancing effect. When any one of the signals was omitted, the immune benefits were incomplete. This highlights how tightly coordinated T cell development is and why previous single-factor approaches may have fallen short.

Broader Implications for Immune Health

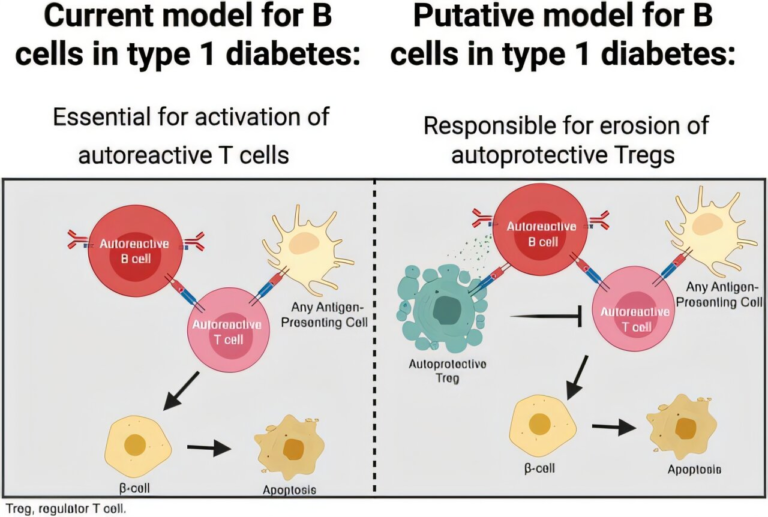

While the study focused primarily on T cells, the researchers believe this approach could have broader effects across the immune system. Future work will explore how the treatment influences B cells, which produce antibodies, as well as other immune cell types involved in long-term immunity and inflammation.

If eventually adapted for use in humans, this strategy could help older adults maintain stronger immune defenses, respond better to vaccines, and gain more benefit from cancer immunotherapies. It also represents a powerful example of how mRNA technology can be used far beyond vaccines, opening the door to temporary, programmable changes in organ function.

What Comes Next

The team plans to test the approach in additional animal models and to identify other signaling molecules that could further enhance immune rejuvenation. Safety, dosing, and long-term effects will all need careful study before any human trials can begin.

Still, the results so far suggest that temporarily turning the liver into an immune-supporting organ could become a new and flexible way to counter immune aging, without permanently altering the body or relying on risky interventions.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09873-4