New Biomarker Shows Promise for Detecting Alzheimer’s Long Before Symptoms

A new study published in Acta Neuropathologica has highlighted the potential of a brain inflammation marker called TSPO (translocator protein 18 kDa) to act as an early warning signal for Alzheimer’s disease. The findings suggest that TSPO levels begin rising years—even decades—before typical symptoms like memory loss and confusion appear. This research could open doors for earlier diagnosis and possibly new treatment strategies.

What the Study Found

Researchers at Florida International University (FIU), led by Dr. Tomás R. Guilarte and first author Daniel A. Martinez-Perez, examined how TSPO behaves in both mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and in human brain tissue from people who carried a genetic mutation linked to early-onset Alzheimer’s.

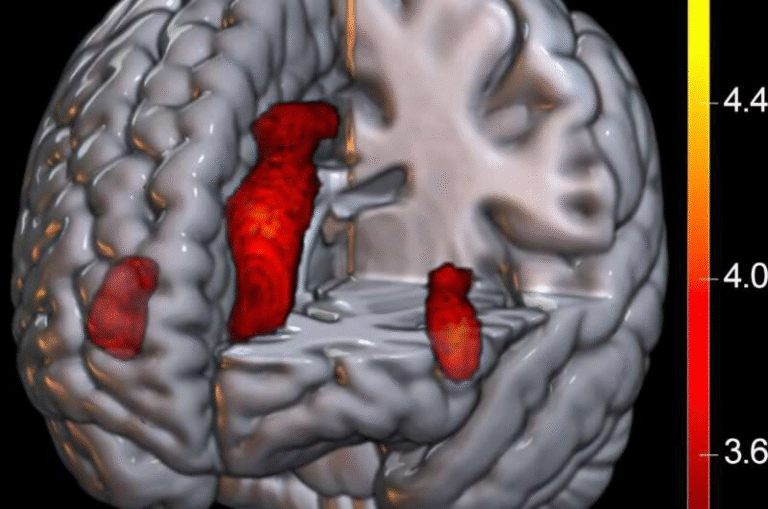

In the mouse experiments, they found that TSPO levels rose very early in the disease process, specifically in the subiculum, a part of the hippocampus important for memory and navigation. This increase appeared as early as six weeks of age in the mice, which the scientists say roughly corresponds to 18–20 years of age in humans. That’s well before memory problems usually become obvious.

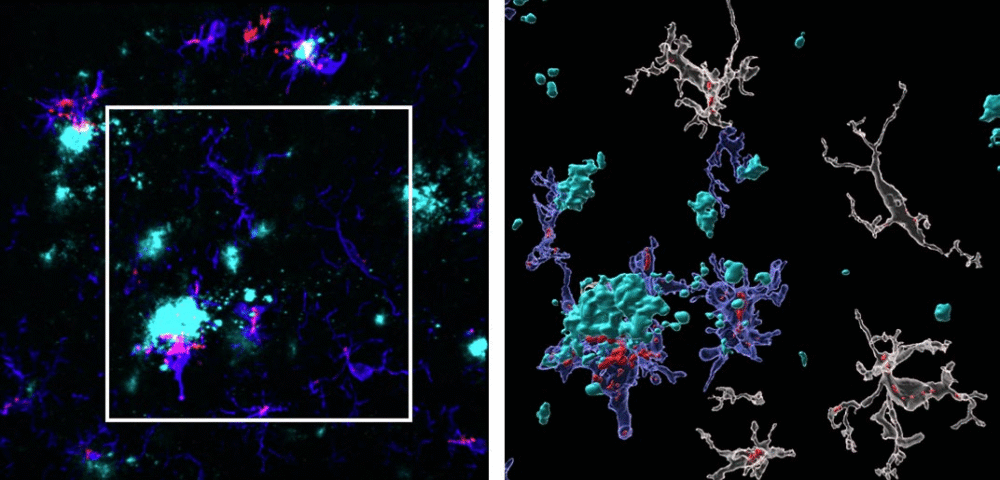

Right: the same image enlarged and processed with specialized imaging software. In this view, microglia (shown in blue) expressing TSPO (red) are seen clustering around amyloid plaques (cyan). This visualization, produced by researchers at Florida International University, illustrates how TSPO—a biomarker of brain inflammation—may help detect Alzheimer’s disease long before symptoms such as memory loss begin.

Credit: Chris Necuze, Florida International University

The rise in TSPO was traced mainly to microglia, the brain’s immune cells, especially those clustering around amyloid-β plaques. These plaques are one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Interestingly, the researchers noted that astrocytes, another type of brain cell involved in inflammation, did not show the same TSPO increase. This suggests microglia are the major players behind this biomarker’s early signal.

When the team looked at human brain samples, they focused on individuals carrying the PSEN1-E280A mutation, also known as the “Paisa mutation.” This genetic variant is found in a large community in Antioquia, Colombia, and is known to cause familial early-onset Alzheimer’s. Carriers often develop symptoms in their 30s or 40s and typically die in their 50s.

The human tissue showed the same pattern as the mice: high TSPO levels in microglia clustered around amyloid plaques. Even in late-stage disease, TSPO remained elevated in these cells.

Sex Differences and Disease Progression

Another striking detail was that female mice had higher TSPO levels than males. This matches what we see in the real world: about two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients are women.

As the disease progressed in mice, TSPO levels continued to increase and spread across more regions of the brain. This spread tracked with the progression of amyloid pathology.

Why This Matters

Alzheimer’s is often diagnosed only after symptoms appear, but by that time, the disease has already caused significant and irreversible brain damage. If TSPO can be used as an early biomarker, doctors might one day be able to detect Alzheimer’s risk years earlier.

Another advantage is that TSPO can be visualized using PET (positron emission tomography) imaging. PET scans are already used in some Alzheimer’s research to look for amyloid or tau proteins. If TSPO PET imaging proves reliable, it could add a powerful new tool for diagnosing and tracking the disease.

Remaining Questions

While these findings are exciting, there are still important unknowns. For example:

- Is TSPO harmful or protective? It’s not clear whether the increase in TSPO contributes to brain damage or is part of the brain’s defense system.

- Does it apply to sporadic Alzheimer’s? Most people develop late-onset Alzheimer’s without a clear genetic cause, and this form accounts for over 90% of all cases. The study so far has focused on familial, early-onset forms of the disease.

- Can TSPO be targeted with treatments? Researchers are now testing Alzheimer’s mouse models that lack TSPO to see whether blocking or enhancing it changes disease progression.

Extra Context: What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, affecting tens of millions of people worldwide. It is a progressive condition that damages brain cells, leading to problems with memory, thinking, behavior, and eventually the ability to perform daily tasks.

Key features of Alzheimer’s include:

- Amyloid-β plaques: sticky protein clumps that build up between nerve cells.

- Tau tangles: twisted strands of protein that build up inside cells.

- Neuroinflammation: chronic activation of immune cells in the brain.

- Loss of neurons and synapses: leading to brain shrinkage and functional decline.

Currently, there is no cure. Some treatments, like lecanemab and donanemab, aim to clear amyloid from the brain, but their long-term benefits remain under study.

Extra Context: What is TSPO?

TSPO, or translocator protein, is found on the outer membrane of mitochondria (the energy-producing structures inside cells). It is widely used as a marker of neuroinflammation.

Scientists can measure TSPO using special radioactive tracers and PET scans. This has made it a useful tool in studying not just Alzheimer’s, but also conditions like Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, depression, and even brain injury.

The fact that TSPO shows up so early in Alzheimer’s progression makes it especially valuable. If doctors can measure it reliably, it could help identify people at risk before symptoms appear.

Extra Context: The Paisa Mutation in Colombia

One of the unique aspects of this study is its use of brain tissue from families in Antioquia, Colombia, who carry the PSEN1-E280A mutation. This mutation is sometimes called the Paisa mutation because it is so common in this community.

- The mutation was first identified by neurologist Dr. Francisco Lopera, who dedicated his career to studying these families.

- People with this mutation often start showing Alzheimer’s symptoms in their 30s or 40s, decades earlier than typical cases.

- Because the age of onset is relatively predictable, these families have been central to Alzheimer’s research worldwide.

By confirming the mouse findings in these human samples, the study strengthens the case for TSPO as a biomarker.

Funding and Research Team

The study was supported by several grants:

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS): ES007062-24 and ES007062-23S1.

- National Institute on Aging: additional support tied to neurodegenerative research.

- Training grant (T32-ES033955) to one of the authors.

The authors include Daniel A. Martinez-Perez, Jennifer L. McGlothan, Alexander N. Rodichkin, Karam Abilmouna, Zoran Bursac, Francisco Lopera, Carlos Andres Villegas-Lanau, and Tomás R. Guilarte.

The Road Ahead

This study is a promising step, but we are still far from applying TSPO in everyday clinical practice. Large-scale human studies, especially in people at risk for sporadic Alzheimer’s, will be essential.

The researchers are now developing mouse models without TSPO to see how the disease behaves when this protein is absent. They are also expanding their work to explore TSPO changes in late-onset Alzheimer’s cases.

If TSPO proves to be a reliable marker, it could mean:

- Earlier diagnosis: identifying Alzheimer’s risk long before symptoms.

- Better monitoring: tracking how the disease changes over time.

- New treatments: targeting TSPO itself or the microglia that drive its increase.

Final Thoughts

The discovery that TSPO rises so early in Alzheimer’s progression is an important development. While many questions remain, it offers hope that one day we might be able to detect—and possibly intervene in—Alzheimer’s disease before it robs people of their memories and independence.

Research Reference:

“Amyloid-β plaque-associated microglia drive TSPO upregulation in Alzheimer’s disease” – Acta Neuropathologica, July 2025