New MRI Method Maps Spinal Cord Blood Flow and Could Transform Injury Treatment

Researchers at Northwestern Medicine have developed a new imaging method that could reshape how we understand and treat spinal cord injuries and degenerative spinal conditions. The technique adapts functional MRI, a tool long used for studying the brain, and applies it to the spinal cord to measure something called vascular reactivity—essentially how well spinal cord blood vessels respond when the body needs more blood flow. This may sound technical, but it has huge potential for conditions where impaired blood supply plays a major role in nerve damage.

The work, published in Scientific Reports in 2025, was led by investigators who wanted to solve a longstanding problem: we’ve never had a reliable, noninvasive way to measure blood flow changes in the spinal cord in real time. Traditional methods simply don’t capture the nuances of how spinal cord blood vessels behave, especially in early disease or after injury. This new approach might fill that gap.

Understanding the Problem of Spinal Cord Blood Flow

Healthy spinal cord tissue depends on a stable and well-regulated blood supply. When that supply is disrupted—even slightly—nerve cells become vulnerable. Conditions like traumatic spinal cord injury and degenerative cervical myelopathy (a disorder caused by age-related disc degeneration and spinal cord compression) often involve some degree of vascular dysfunction, which may worsen symptoms such as weakness, numbness, or coordination difficulties.

But despite how important blood flow is, researchers have struggled to measure it accurately. The spinal cord is a challenging area to image because it’s small, constantly moving with the heartbeat and breathing, and surrounded by bone and cerebrospinal fluid that distort MRI signals. Earlier imaging techniques either lacked precision or didn’t truly measure how blood vessels respond to stress or demand.

The Northwestern team set out to change that.

How the New Imaging Approach Works

Their method adapts functional MRI (fMRI), a tool that typically maps brain activity by detecting changes in blood oxygen levels. Instead of looking for neural activity, the researchers used fMRI to directly track how blood vessels in the spinal cord react when carbon dioxide levels rise.

To create this reaction, study participants did something surprisingly simple during the MRI scan: brief breath holds. Holding your breath causes carbon dioxide to accumulate in the bloodstream. In response, blood vessels naturally dilate to increase blood flow. This dilation is a measurable signal, allowing scientists to see which regions of the spinal cord respond most strongly and how quickly.

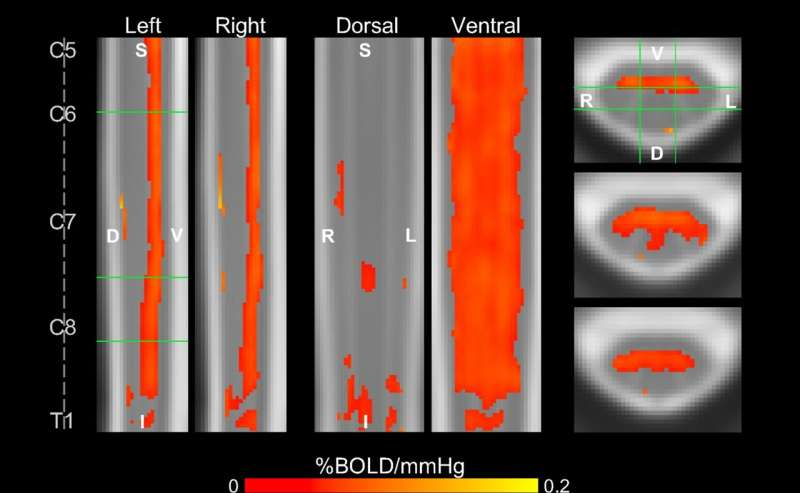

From these scans, the researchers generated detailed vascular reactivity maps showing both the amplitude of blood-flow changes and the timing of those responses. One interesting finding was that different spinal cord regions responded at different times, a pattern that appeared consistently across participants. The team believes these timing differences may reflect the behavior of different arteries that supply the spinal cord—patterns that, until now, had never been mapped noninvasively in humans.

This is a notable milestone because it suggests the technique is not just measuring blood flow—it may also reveal the structure and function of spinal cord circulation itself.

Why This Approach Could Change Treatment

The practical implications could be significant.

For individuals with spinal cord injury, doctors often struggle to determine whether treatments—whether surgical, rehabilitative, or pharmacological—are improving function in the damaged areas. With this imaging method, clinicians could potentially track vascular improvements alongside neural activity, giving a clearer picture of recovery.

Meanwhile, people with degenerative cervical myelopathy may benefit from earlier detection. Before nerves become permanently damaged, the surrounding blood vessels often show impairment. If this imaging technique identifies vascular dysfunction near areas of spinal compression, doctors might decide that patients need closer monitoring or earlier intervention.

The broader idea is that mapping vascular health—alongside more traditional neural imaging—could help personalize care. Instead of relying only on structural scans showing compression or degeneration, clinicians may be able to see how the spinal cord is actually functioning on a physiological level.

What Makes Spinal Cord Imaging So Difficult?

To appreciate the breakthrough, it helps to understand the biological and technical challenges behind spinal cord imaging.

The spinal cord’s blood supply is unusually complex. Unlike the brain, which has a well-mapped and relatively consistent vascular system, the spinal cord is fed by a mix of longitudinal arteries and numerous smaller radicular and segmental arteries. The pattern varies from person to person. This variability makes it tricky to interpret blood-flow signals without high-resolution maps.

On top of that, the spinal cord is a narrow structure—only about the diameter of a finger—and sits inside a bony canal. Movement from breathing and blood pulsation adds noise. MRI machines also have difficulty maintaining consistent magnetic fields around the spine because of nearby tissues with different densities. All these factors degrade image quality and complicate measurement.

Older perfusion methods, like arterial spin labeling (ASL), have been attempted in the spinal cord, but they often struggle with low signal strength and inconsistent results. Some research groups tried specialized high-field MRI scanners, but those are not widely available clinically.

The new approach stands out because it uses standard fMRI techniques, refined and adapted specifically for spinal anatomy. By pairing breath-hold challenges with sophisticated modeling of carbon dioxide levels and timing shifts, the researchers overcame many limitations that held previous methods back.

What the Study Revealed

The findings showed:

- Clear mapping of vascular reactivity across multiple spinal cord regions

- Strong, consistent responses on the ventral side of the cord

- Distinct timing variations in vascular response that correspond to potential arterial flow patterns

- Successful generation of reactivity maps at both the individual and group level

These outcomes demonstrate that the method is robust enough to be replicated across different people—an essential requirement for any tool that might move into clinical use.

Where This Research Might Lead Next

While the study involved healthy volunteers, the next steps will be to test the technique in individuals with known spinal conditions. Researchers will need to determine whether reduced or delayed vascular reactivity correlates with symptoms, prognosis, or treatment outcomes.

If validated, SCVR mapping could eventually complement standard spinal MRI in clinics. For example, surgeons might use it to decide whether a patient with mild spinal cord compression should undergo early decompression. Rehabilitation physicians might use it to track recovery after spinal cord injury. Researchers might use it to better understand how aging or chronic inflammation affects spinal circulation.

There’s also potential for integration with other advanced imaging tools, such as diffusion MRI or electrophysiological measures. Combining vascular, structural, and neural data could yield a far more complete picture of spinal cord health than we currently have.

Additional Background: Why Vascular Health Matters in the Spine

Blood vessels and nerve cells depend heavily on each other. When spinal cord blood flow is compromised, even briefly, the tissue can develop inflammation, impaired signaling, and in severe cases, cell death. Many spinal diseases follow a similar pattern: a period of vascular dysfunction precedes irreversible neural damage.

For example:

- In traumatic injury, swelling and disrupted blood flow are major contributors to secondary damage.

- In degenerative cervical myelopathy, chronic compression squeezes the cord and its vessels, leading to periods of reduced perfusion.

- In metabolic or autoimmune conditions, inflammation can impair vascular function long before structural changes appear on MRI scans.

This is why measuring vascular reactivity—not just structure—is so important. It tells us how the cord responds under stress, something structural imaging alone cannot do.

The Road Ahead

The Northwestern team’s work represents an encouraging step toward more functional, physiology-based spinal imaging. While the method must still be tested more broadly, the ability to generate detailed maps of spinal cord blood-flow dynamics is itself a major accomplishment.

As imaging technology continues to advance, we may soon have a richer understanding of how the spinal cord functions in real time—and new tools to detect problems long before symptoms become severe.

Research Paper:

MRI mapping of hemodynamics in the human spinal cord