New Research Reveals How Shape-Shifting Tumors Work and Uncovers New Targets for Future Cancer Therapies

Scientists have uncovered new details about why certain carcinomas are so difficult to treat, especially those known for their unusual ability to change their identity. These cancers, which often behave like cellular shapeshifters, can begin to resemble entirely different tissues—such as skin cells—making them extremely resistant to conventional treatments. New findings from the Vakoc lab at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) now offer a clearer view of how these tumors operate at the molecular level, and more importantly, where they may be vulnerable.

The research spans two major studies. One focuses on pancreatic cancer and how its cells switch between different identity programs. The other uncovers the structural makeup of a master regulator that drives a rare but aggressive form of lung cancer known as tuft cell lung cancer. Together, these studies move scientists closer to developing highly specific, less toxic cancer therapies based on controlling cellular identity.

Understanding Why Some Tumors Change Identity

Many carcinomas become resistant to treatment because they don’t stay committed to one cell type. They can activate different genetic programs and transform themselves, making them harder to target with traditional therapies. These tumors show extreme plasticity, meaning they can modify their cellular identity in ways that help them survive.

For years, the Vakoc lab has centered its work on identifying the master regulators that control these identity states. If scientists can understand what determines a tumor cell’s “identity,” they can begin developing treatments that block the regulators responsible, forcing the tumor out of the identity program it relies on to grow.

Newly Identified Controller in Pancreatic Cancer

In a study published in Nature Communications, CSHL researchers report that a protein called KLF5 plays a key role in determining whether pancreatic cancer cells maintain their classical identity or shift into a skin-like, more aggressive form. Pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to treat, partly because tumors often contain a mix of cell states. When cells adopt the skin-like identity, they tend to become more resistant to therapy.

Researchers found that KLF5 does not work alone. It relies heavily on two AAA+ ATPase coactivator proteins, RUVBL1 and RUVBL2, which help activate the different lineage programs. These coactivators are involved in ATP-dependent processes—essentially, they provide the energy or structural support KLF5 needs to function.

Scientists demonstrated that disrupting RUVBL1 and RUVBL2 prevents KLF5 from binding efficiently to the DNA regions that control identity programs. This finding is particularly important because inhibitors targeting RUVBL1/2 already exist. In mouse models of pancreatic cancer, these inhibitors suppressed tumor growth without detectable damage to vital organs.

This suggests a possible therapeutic path that targets a regulatory system cancer cells rely on, rather than targeting specific genetic mutations. Because the KLF5-RUVBL1/2 mechanism supports multiple identity states, inhibiting it could work across different pancreatic cancer subtypes.

Structural Discovery in Tuft Cell Lung Cancer

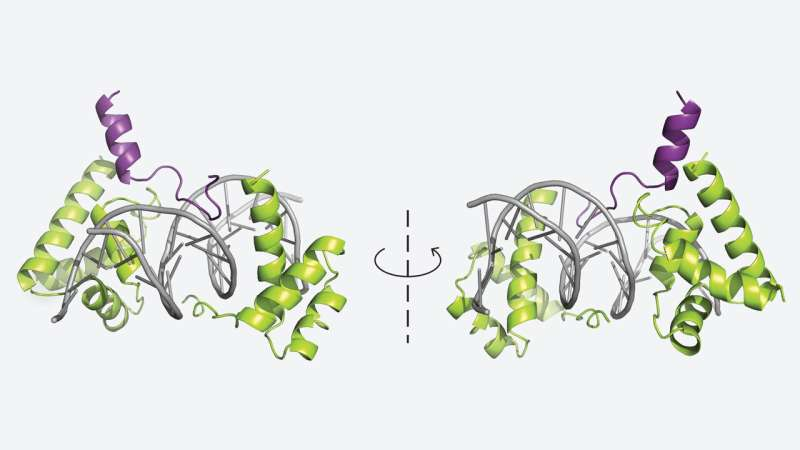

In a second study published in Cell Reports, Vakoc’s team collaborated with CSHL Director of Research Leemor Joshua-Tor to investigate POU2F3, a master regulator essential for tuft cell lung cancer. This is a rare form of cancer identified by the Vakoc lab in 2018, and it behaves differently from typical lung cancers.

The researchers resolved the crystal structure of a three-part molecular interface:

- the transcription factor POU2F3,

- the coactivator protein OCA-T1, and

- the DNA sequence they bind to.

This marks the first time scientists have seen the detailed physical arrangement of this regulatory complex. Understanding this structure is a major breakthrough because it shows exactly how POU2F3 recruits coactivator proteins to activate the genes tuft cell cancers need to survive.

To map the functional importance of different sections of these proteins, the researchers conducted a deep mutational scan, analyzing more than 4,200 missense variants of POU2F3 and OCA-T1. This allowed them to identify specific “hotspots” on both proteins where even small changes disrupt their activity. These hotspots could become targets for future drug development.

When the researchers inhibited POU2F3 or OCA-T1 in tuft-cell-like lung tumor models, the tumors regressed. Importantly, in mouse studies, there was no evidence of toxicity or damage to normal tissues. This suggests that future therapies aimed at this complex could be both effective and highly selective.

Why These Studies Matter

Both studies reflect a shift in cancer research toward epigenetic and transcriptional regulation—that is, understanding how cancers control gene expression rather than focusing solely on genetic mutations. Many cancers rely on identity-determining regulators to maintain their malignant behavior. This opens opportunities for epigenetic therapies that disrupt these regulatory networks directly.

A key advantage of this approach is specificity. The goal is to design drugs that:

- interfere with the cancer’s identity program,

- leave healthy tissues unaffected, and

- reduce the harmful side effects often associated with chemotherapy and radiation.

The Vakoc lab is focused on setting a high standard for specificity. In both the pancreatic and lung cancer studies, the targeting strategy showed no signs of organ toxicity in animal models. This is crucial if these findings eventually lead to clinical treatments.

Additional Background: What Makes a Master Regulator Special?

A master regulator is a protein—usually a transcription factor—that controls large networks of genes responsible for establishing and maintaining a cell’s identity. In normal development, master regulators determine whether a cell becomes, for example, a neuron, a liver cell, or a skin cell.

In cancer, however, these regulators can become hijacked. Tumor cells may activate identity programs they shouldn’t have access to. This is often how they become more aggressive or evade treatment.

Master regulators are extremely powerful because:

- they sit at the top of gene-expression hierarchies,

- a small change in their activity can reshape the entire cell,

- they often create vulnerabilities unique to cancer cells.

This makes them attractive—but historically difficult—targets for therapy. Structural studies like the one conducted on the POU2F3 complex are vital because they reveal practical ways to design drugs around these regulators.

A Growing Field: Targeting Cancer Identity

Cancer researchers are increasingly interested in targeting cellular identity for several reasons:

- Identity drives behavior — A tumor’s identity program influences how fast it grows, how it spreads, and how it responds to treatment.

- Identity can change — Some of the hardest cancers to treat survive by switching identity, allowing them to escape therapies designed for their original state.

- Master regulators offer leverage — Disrupting a master regulator can collapse the entire identity program, weakening the tumor across multiple fronts.

The two new studies from the Vakoc lab fit directly into this expanding area of research and add important structural and mechanistic details that were previously missing.

Research References

Nature Communications – https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66007-0

Cell Reports – https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.116572