New Research Reveals How T Cells Transform Into Powerful Organ-Defending Immune Cells

Scientists have uncovered a key biological mechanism that helps certain immune cells permanently take up residence inside our organs, where they act as rapid defenders against infections, tumors, and other threats. These cells, known as tissue-resident memory T cells or TRM cells, don’t circulate through the bloodstream like most T cells. Instead, they settle into specific tissues — such as the lungs, liver, skin, and other organs — and stay there for long-term protection. A new study from researchers at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) not only explains how TRM cells develop but also points to a molecular target that could one day help doctors strengthen the body’s local immune defenses or, in some cases, dial them down.

At the center of this discovery is a molecule called GPR25, a type of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). These receptors sit on the surface of cells and translate external chemical signals into internal cellular actions. GPCRs are already well known in medicine because they are considered highly druggable — meaning they can be targeted by therapies more easily than many other molecular structures. In fact, close to 30% of the drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration act on some member of the GPCR family. The finding that GPR25 plays a major role in TRM cell development opens the door to potential strategies aimed at boosting immunity against infections and cancers or suppressing harmful immune activity in autoimmune conditions.

Researchers at LJI have been studying TRM cells for years, and previous work revealed that these cells express unusually high levels of GPR25 on their membranes. This stood out immediately because most memory T cells do not display such strong expression of this receptor. The team suspected that GPR25 must be involved in driving TRM cell development, but the specifics were still unclear. With advancements in immune cell profiling and genetic tools, scientists were finally able to pinpoint how GPR25 fits into the picture.

The new study shows that TRM cell formation depends heavily on a powerful signaling molecule called TGF-β. In the immune system, TGF-β pushes certain T cells toward specialized fates, including becoming tissue-resident cells. Researchers discovered that TGF-β directly induces the production of GPR25. Once present, GPR25 helps maintain the downstream TGF-β signaling pathway, ensuring that a memory T cell fully commits to becoming a TRM cell. Without sustained signaling, the transformation process weakens or fails.

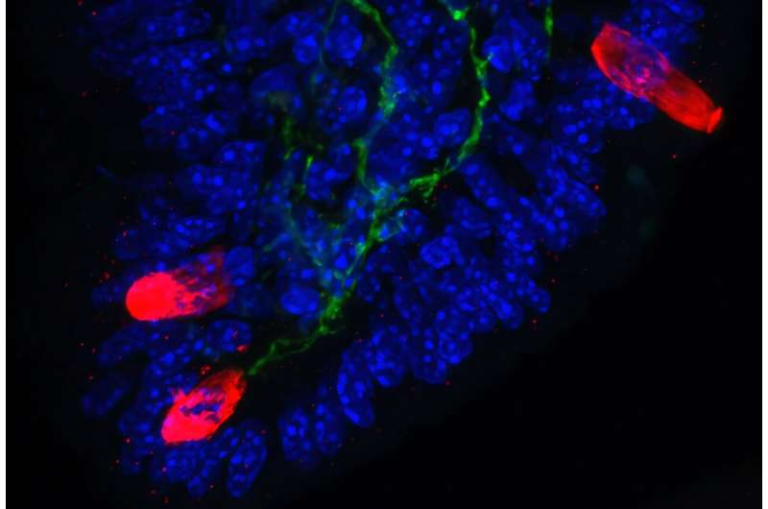

To understand GPR25’s function more clearly, scientists used genetically engineered mice that lacked GPR25. They examined TRM cells in lung and liver tissue, two organs where these cells play a particularly important role in fighting infections and tumors. The results were striking: mice without GPR25 could not maintain a proper population of TRM cells. Their immune cells also showed defective TGF-β signaling, confirming that GPR25 is not merely a surface marker but an essential piece of the TRM-development machinery.

Further experiments revealed that adjusting GPR25 activity — either enhancing or suppressing it — changed how effectively TRM cells formed. This is significant, because increasing TRM numbers could help the body respond more forcefully to viruses or cancers, while reducing TRM activity could benefit patients with autoimmune diseases where these cells trigger damaging inflammation.

The LJI team also emphasized that GPCRs like GPR25 are excellent drug targets because their location on the cell membrane makes them accessible to therapeutic molecules. Many existing medications take advantage of this ease of access. The hope is that one day, manipulating GPR25 could become a practical medical strategy: boosting TRM populations to improve cancer survival rates or infection resistance, or reducing TRM-driven inflammation in diseases where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue.

This discovery becomes even more meaningful when we consider the broader role of TRM cells in human health. Since their formal identification as a distinct immune cell population in 2009, TRM cells have gained attention for their extraordinary capabilities. They act as first responders, identifying threats in tissues long before circulating immune cells can arrive. Studies have shown that TRM cells can target viruses, breast cancer, liver cancer, melanoma, and other conditions. In fact, research led by scientists such as Pandurangan Vijayanand, a senior figure in this field, has demonstrated that patients with higher TRM cell density in their lung tumors tend to have better survival outcomes.

Even though TRM cells are powerful, their formation process is complicated. They require specific environmental cues from the tissue, precise surface-receptor signaling, and stable exposure to molecules like TGF-β. The discovery of GPR25’s role brings scientists closer to mapping this process in full. A deeper understanding of TRM development could influence vaccine design, cancer therapy, antiviral strategies, and treatments for chronic inflammatory diseases.

To give readers additional context, it’s helpful to understand how TRM cells differ from other T cells. Most T cells circulate through the bloodstream, moving between lymph nodes and peripheral tissues in search of pathogens. Memory T cells, which form after an infection or vaccination, help the body respond faster the next time it encounters the same threat. TRM cells, however, take this protection a step further by permanently embedding themselves in the tissue where an infection or tumor once appeared. Instead of patrolling the entire body, they stay at a strategic location and provide rapid, localized defense.

TRM cells often express markers such as CD69, CD49a, and sometimes CD103, which help them stay within tissues rather than re-entering circulation. Their unique positioning has made them a major focus in the field of mucosal immunology, cancer immunotherapy, and vaccine research. Because many pathogens enter the body through mucosal surfaces, such as the airways or digestive tract, TRM cells stationed in those regions may offer stronger protection than circulating immune cells alone.

However, TRM cells are not universally beneficial. In some cases, particularly in autoimmune disorders, they can contribute to chronic and harmful inflammation. This dual nature is another reason why the discovery of GPR25 is significant: modulating this receptor could give scientists a precise way to tune TRM activity up or down, depending on what a disease requires.

The research now raises several future questions. For example, do human TRM cells rely on GPR25 in exactly the same way mouse TRM cells do? Can small-molecule drugs be safely developed to target this receptor without causing unwanted immune activation? And how might GPR25-based therapies interact with existing cancer immunotherapies or antiviral treatments?

What is clear is that this new work lays a strong foundation for exploring these possibilities. It identifies a crucial molecule that helps memory T cells become long-term residents in organs and offers a tangible path toward medical applications. As scientists continue to uncover the hidden communication networks inside our immune system, findings like this bring us closer to using the body’s natural defenses more effectively.

Research Reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciimmunol.adu2089