New Research Sheds Light on Genetic Factors Behind Pediatric Brain and Spinal Cord Tumors

A major new study from teams at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. is offering a clearer picture of how rare inherited genetic variants influence the development of brain and spinal cord tumors in children. Published in Nature Communications, this research digs deep into the genetics behind pediatric central nervous system (CNS) cancers, which continue to be the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among children. A staggering 47,000 children and young adults worldwide face diagnoses of CNS tumors every year, yet many of the inherited risks remain hidden during routine medical care.

Below is a detailed, straightforward breakdown of the findings and what they mean, along with additional background information to help readers understand the broader context of pediatric cancer genetics.

What the Researchers Set Out to Learn

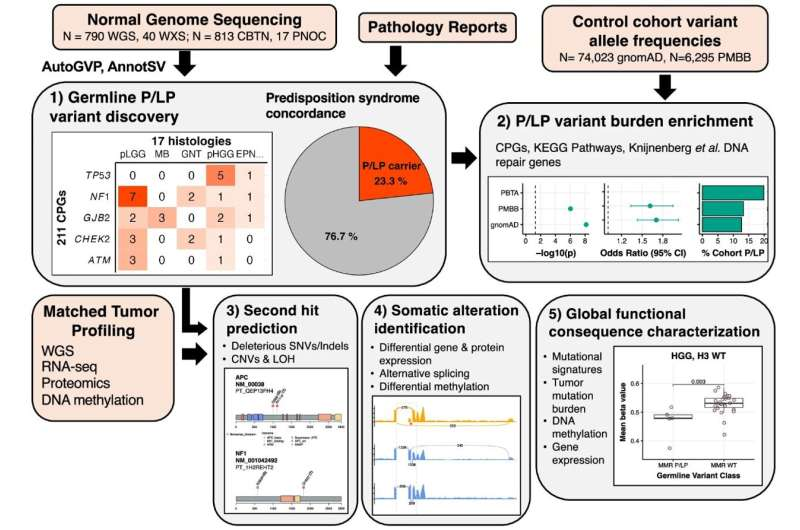

Although previous studies have suggested that up to 1 in 4 children with cancer carry rare genetic variants that increase cancer susceptibility, the specific inherited factors that contribute to pediatric CNS tumors have been unclear. This research focused on whether pathogenic (P) and likely pathogenic (LP) germline variants—genetic changes present from birth—play a meaningful role in tumor risk, tumor biology, and clinical outcomes.

Credit: Nature Communications (2025).

The study used data from 830 children diagnosed with brain and spinal cord tumors. These samples came from the Pediatric Brain Tumor Atlas, a large international resource containing genetic, molecular, and clinical data from childhood tumor cases. The researchers analyzed both blood samples (representing inherited DNA) and tumor samples (representing acquired mutations) to look for inherited variants associated with cancer risk. They then compared these results to the children’s medical histories to see whether any tumor-predisposition syndromes had already been recognized in clinical settings.

Key Findings: Genetic Risk Is More Common Than Expected

One of the clearest takeaways from the study is that inherited cancer-predisposition variants are significantly under-recognized in children with CNS tumors.

Here are the most important findings:

- 23.3% of the children — nearly 1 in 4 — carried a P or LP germline variant in a gene known to increase cancer risk.

- 7% (a total of 57 children) had already been diagnosed with a known genetic condition linked to tumor development.

- An additional 6% (48 children) carried genetic variants associated with CNS tumors but had not yet been clinically recognized as having any genetic predisposition.

- This means many children are walking around with inherited or early-arising genetic risks that current medical procedures simply don’t detect.

The study strongly suggests that routine genetic screening for pediatric brain and spinal cord cancer patients could identify risks far earlier and more accurately than current clinical practice allows.

How Inherited Variants Influence Tumor Development

Another major insight from the research involves how these inherited variants interact with mutations that arise within the tumor.

Among children carrying P or LP germline variants:

- 35% had an additional alteration in the same gene within their tumor.

- This often resulted in the loss of normal gene function.

This supports the famous two-hit model of cancer development, where:

- A harmful variant is inherited (the first hit).

- A second mutation arises in the tumor tissue (the second hit).

Together, these hits disable key tumor-suppressing genes and contribute to cancer progression.

The study demonstrates that this inherited-plus-acquired combination not only increases cancer risk but also shapes how aggressive the tumor becomes and how a child’s disease will behave over time.

Why This Changes How We Understand Pediatric CNS Cancers

Historically, CNS tumors in children have been viewed mostly through the lens of randomly occurring mutations in the developing brain. This study shifts that perspective by emphasizing that inherited genetics play a bigger role than previously recognized.

The findings suggest several major implications:

1. Genetic Screening Should Become Standard for Pediatric CNS Tumors

Current diagnostic approaches miss far too many cancer-predisposition syndromes. Expanded germline testing could:

- Identify risk earlier

- Improve monitoring for tumor progression

- Allow more personalized treatment strategies

2. Inherited Variants Influence Tumor Behavior

Knowing whether a child carries a high-risk variant could help predict:

- Tumor aggressiveness

- Likely treatment response

- Overall prognosis

3. Family Genetic Testing May Also Be Useful

Because some variants are inherited, parental testing (which the researchers plan to incorporate next) could identify at-risk siblings and guide earlier screening.

4. Research on Pediatric CNS Tumors Needs Even Larger Datasets

The team plans to more than double the number of patients in the next phase of the study and include parental sequencing. This will help distinguish between inherited versus de novo (newly occurring) variants.

Extra Context: Understanding Germline Variants and Tumor-Predisposition Genes

Since this topic involves specialized genetics, here is an accessible overview to help readers better understand the science behind the study.

What Are Germline Variants?

These are genetic differences present in a child from birth, either inherited from a parent or forming very early in development. They exist in every cell of the body, including tumor cells.

When harmful, germline variants can:

- Weaken tumor-suppressor genes

- Disrupt DNA-repair systems

- Increase vulnerability to cancer-causing mutations

What Are Pathogenic and Likely Pathogenic Variants?

- Pathogenic (P): Known to increase disease risk

- Likely pathogenic (LP): Strong evidence of risk but not yet definitive

Together, they form a crucial category of variants that clinicians look for when considering genetic predisposition.

Common Genes Involved in Pediatric CNS Tumors

While this specific study includes many genes, tumor-predisposition in children often involves genes like:

- TP53 (linked to Li-Fraumeni syndrome)

- NF1 (neurofibromatosis type 1)

- PTCH1 and SUFU (linked to medulloblastoma)

- SMARCB1, SMARCA4 (genes involved in chromatin remodeling)

Not all genes were discussed in the news summary, but these are commonly implicated in pediatric CNS tumor biology.

Why CNS Tumors in Children Are Unique

Pediatric brain tumors behave very differently from adult tumors. Children’s developing brains:

- Have different cellular environments

- Undergo rapid growth

- Respond differently to mutations

This makes understanding inherited risk factors especially important, since early-life mutations may interact with the natural developmental landscape of the brain.

Looking Ahead: What This Study Means for Families and Clinicians

The potential clinical impact of this study is substantial. If more children undergo genetic screening at diagnosis, clinicians may be able to:

- Detect tumor-predisposition earlier

- Implement closer surveillance

- Customize therapy based on genetic risk

- Better understand which patients are likely to face more aggressive disease

As research continues, especially with the upcoming expansion of this project, we may see major changes in how pediatric brain and spinal cord tumors are diagnosed and managed worldwide.

Research Paper Reference

Germline pathogenic variation impacts somatic alterations and patient outcomes in pediatric central nervous system tumors

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65190-4