New Research Sheds Light on Why Human Bodies Reject Transplanted Pig Kidneys and How Scientists Successfully Reversed It

Efforts to use genetically modified pig kidneys as an alternative source of organs have taken a major leap forward, thanks to a detailed two-month investigation led by researchers at NYU Langone Health. Their new findings reveal, step by step, how the human immune system reacts to a pig kidney—and, more importantly, how these reactions can be predicted and reversed using existing FDA-approved medications.

This research is especially significant given that more than 800,000 Americans currently live with late-stage kidney disease, yet only about 3% receive a transplant each year. With human donor organs in critically short supply, scientists see pig organs as one of the most promising long-term solutions to the transplant shortage.

Below is a straightforward breakdown of what the researchers learned, how they learned it, and why their work matters for the future of medicine.

A Unique Look Inside the Human Immune Response to a Pig Kidney

To investigate why pig kidneys are often rejected despite advanced genetic modifications, scientists transplanted a gene-edited pig kidney into a brain-dead human recipient whose family donated his body for research. The recipient had a beating heart and was maintained on a ventilator, enabling the pig kidney to function in a real human biological environment.

Over 61 days, the team collected frequent samples of blood, fluid, and tissue—something that cannot be safely or ethically done with living transplant patients or non-human primates. This allowed them to track, in extraordinary detail, the sequence of immune events that occur during both stable graft function and episodes of rejection.

What They Found: Antibodies and T Cells Drive Rejection

In the first of the two new Nature studies, researchers mapped how both human and pig immune components behaved as the organ settled in and later encountered rejection.

They found that rejection was driven by two major forces:

- Antibodies, which tag foreign material for immune attack

- T cells, which directly target and destroy cells perceived as non-self

This dual response explains why even heavily gene-edited pig organs still face obstacles inside the human body. Pig kidneys used in xenotransplants are modified to remove or dampen the biological markers that human antibodies normally latch onto, but the study showed that the immune system still perceives the organ as foreign in multiple ways.

Crucially, once the researchers identified these specific immune mechanisms, they were able to reverse the rejection episode using a combination of medication that is already widely approved and used for human organ transplants. After treatment, there was no sign of irreversible tissue damage or lasting decline in kidney function.

Mapping Every Immune Cell and Gene Over 61 Days

In the second Nature paper, the team went even deeper. They conducted a multi-omics analysis, a comprehensive approach that integrates:

- Gene function

- Gene expression

- Protein signals

- Cellular activity

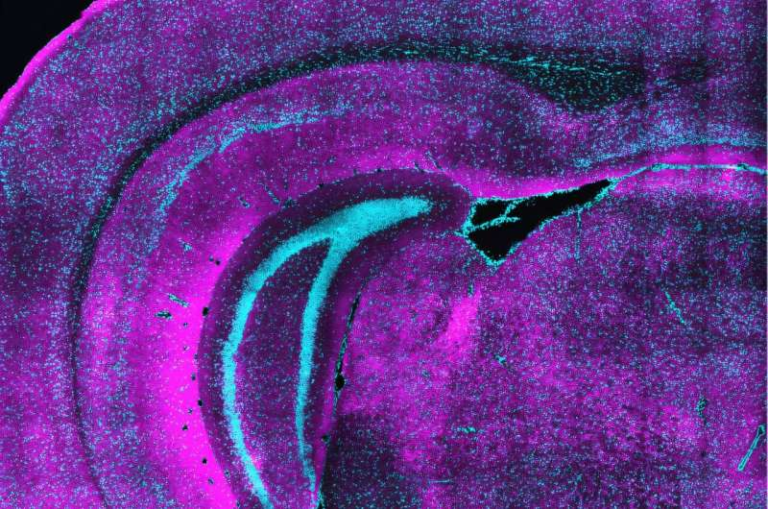

More than 5,100 human and pig genes were analyzed in the transplanted kidney. Researchers identified every type of immune cell present in the tissue and traced how their activity changed each day during the two-month study period.

Three distinct immune attacks were observed:

- Postoperative Day 21 (POD 21) – An attack driven by the innate immune system, the part of human immunity that responds broadly to foreign invaders.

- POD 33 – A response dominated by macrophages, the white blood cells that engulf and digest unfamiliar cells.

- POD 45 – A powerful, targeted attack led mostly by T cells.

These events were not random surges—scientists could trace them directly to specific immune pathways and cellular interactions.

Early-Warning Biomarkers Could Change How Xenotransplants Are Managed

One of the most promising findings was that changes in blood biomarkers could detect immune attacks up to five days before they became visible in tissue biopsies. That means future doctors could potentially intervene before the organ suffers measurable damage.

The researchers say these biomarkers could serve as an early-warning system, helping clinicians monitor pig organs more effectively and tailor immune-suppressing treatments with greater precision.

Why Pig Kidneys Are a Focus of Transplant Research

To understand why this work matters, it helps to know why scientists often look to pigs when considering xenotransplantation (the transplantation of organs across species).

Pigs make suitable organ donors because:

- Their organs are similar in size and function to human organs.

- Their biological systems are compatible enough that genetic engineering can reduce rejection risk.

- They reproduce quickly and can be bred in controlled, pathogen-free environments.

In recent years, biotechnology companies—most prominently Revivicor, which provided the gene-edited pig for this study—have developed pigs with multiple gene edits, such as:

- Removing carbohydrate molecules that trigger human antibodies

- Adjusting pig genes related to immune activation

- Adding human genes that help the body tolerate the organ

These edits have created pig kidneys that function well in non-human primates for several months and, more recently, have worked for shorter periods in human clinical cases.

How This Research Fits Into the Larger Xenotransplantation Landscape

This study is part of a rapidly evolving field. In the past three years, several major firsts have occurred:

- Gene-edited pig kidneys have been transplanted into living human patients under compassionate-use approvals.

- A handful of patients have survived months with functioning pig kidneys.

- Trials for pig kidney transplants in living humans are either underway or preparing to begin at major centers like NYU Langone, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Massachusetts General Hospital.

This newest research stands out because it offers the most comprehensive biological dataset ever gathered from a pig-to-human transplant. It answers not just “what happened,” but “why it happened,” giving scientists the clearest roadmap yet for designing better therapies.

What Comes Next for the Researchers

Now that they know which antibodies, which T cells, and which pathways are responsible for the rejection, the team plans to investigate exactly which molecular targets the immune system is attacking.

Their next steps include:

- Using DNA, RNA, and protein data to pinpoint precise immune targets

- Repeating the study in additional human decedents

- Conducting research in live patients during upcoming clinical trials

With several layers of data collected—genetic, cellular, and biochemical—scientists now have a powerful foundation for improving the next generation of pig kidneys.

Why This Matters for the Future of Kidney Transplants

If xenotransplantation becomes safe and reliable, it has the potential to transform global transplant medicine. For the first time, patients would not be limited by human donor availability. People with late-stage kidney disease could receive transplants sooner, live longer, and rely less on dialysis.

This particular study provides optimism because it demonstrates:

- How rejection begins

- How it progresses

- How it can be identified early

- How it can be reversed

And importantly, it shows that a pig kidney can successfully perform the functions of a human kidney during extended periods, even as the immune system mounts complex attacks.

While the path toward routine xenotransplantation is still long, these findings mark one of the clearest steps forward yet.

Research Paper Reference:

Physiology and Immunology of Pig-to-Human Decedent Kidney Xenotransplant

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09847-6