New Research Shows How Gene Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia Works by Breaking a Three-Dimensional Genome Structure

Gene therapy for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia has already delivered life-changing results for many patients, but there has always been a major question lingering in the scientific community: How exactly does this treatment work at the molecular level? A new study from researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and Northwestern University, published in Blood (2025), finally answers that question — and even uncovers a promising new treatment possibility that may one day make therapy far more accessible.

Below is a clear and detailed breakdown of everything revealed in the study, plus additional context for readers who want to understand why this discovery matters and how it fits into the broader genetics and hemoglobin landscape.

How Current Gene Therapy for These Diseases Works

Modern CRISPR-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia targets a specific regulatory DNA sequence called an enhancer. This enhancer controls the expression of BCL11A, a gene that plays a major role in switching the body’s hemoglobin production from fetal hemoglobin to adult hemoglobin after birth.

BCL11A’s job is quite direct:

- It represses fetal hemoglobin,

- which forces the body to rely on adult hemoglobin,

- and in patients with either sickle cell disease or β-thalassemia, adult hemoglobin is faulty or inadequate.

Therapies that silence or disrupt BCL11A allow fetal hemoglobin to return. And fetal hemoglobin can compensate extremely well for the defects of adult hemoglobin, making it an incredibly powerful therapeutic strategy.

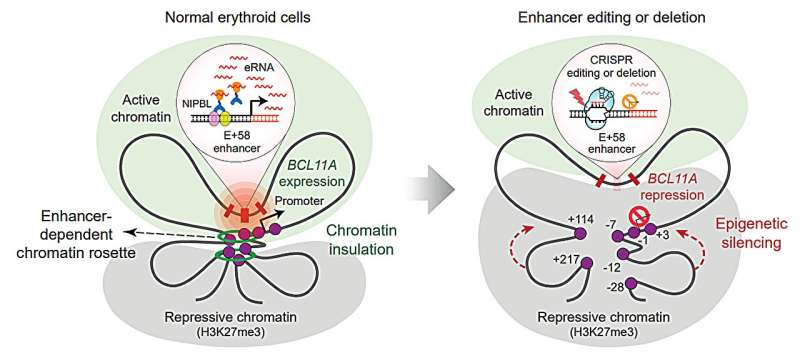

The New Discovery: A Three-Dimensional Chromatin “Rosette”

This new study reveals that the enhancer targeted by CRISPR isn’t just a flat piece of DNA—it folds into a three-dimensional chromatin structure described as a chromatin rosette.

Here is what the scientists found:

- This rosette structure allows the enhancer to form multiple contacts with several other regulatory elements of the BCL11A gene.

- These interactions keep BCL11A expression high in red-blood-cell precursors.

- High BCL11A expression ensures fetal hemoglobin stays shut off during normal development.

So the therapy works not simply because CRISPR mutates the enhancer—it works because damaging the enhancer breaks apart the entire rosette structure, which the gene depends on to stay active.

Once this structure collapses:

- Repressive proteins can finally access and silence BCL11A.

- BCL11A levels drop.

- Fetal hemoglobin reactivates, restoring oxygen-carrying capacity in red blood cells.

This is the first time scientists have shown that BCL11A depends on a 3D architectural structure to maintain its expression in blood-forming cells.

Enhancer RNA Is Another Key Part of the Puzzle

The research team also discovered that the rosette structure relies on a special type of RNA called enhancer RNA (often abbreviated as eRNA). Enhancer RNAs are produced from enhancer regions and can help maintain regulatory structures within the genome.

In this case, the enhancer RNA is essential for:

- stabilizing the chromatin rosette,

- and helping recruit a protein complex involved in chromosome organization.

Without this enhancer RNA, the whole structure becomes vulnerable.

A New Treatment Idea: Antisense Oligonucleotides

After discovering that enhancer RNA is crucial, the researchers tested whether removing that RNA alone could cause the same therapeutic effect.

They used antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) — small synthetic molecules that can bind to and degrade RNA.

When they delivered these ASOs into both normal and sickle cell precursors, they found that:

- the enhancer RNA was depleted,

- the BCL11A chromatin structure destabilized,

- BCL11A was silenced,

- and fetal hemoglobin was reactivated.

This is a major finding because ASO-based therapy:

- does not involve genome editing,

- does not require stem-cell transplantation,

- can theoretically be administered more easily,

- and could potentially cost far less.

Given that current gene therapies are extremely expensive, limited to specialized centers, and involve significant clinical complexity, an ASO-based alternative could open treatment access to millions more patients worldwide.

Why Silencing BCL11A Works So Well

To understand why all of this is so important, it helps to know what makes fetal hemoglobin such a powerful solution.

BCL11A and the Hemoglobin Switch

Humans naturally transition from fetal hemoglobin (HbF) to adult hemoglobin (HbA) after birth. BCL11A is one of the major regulators enforcing this switch. When BCL11A is active:

- HbF is suppressed

- HbA takes over

For most people, this works fine. But in those with sickle cell disease or β-thalassemia, adult hemoglobin is either abnormal or insufficient. Reactivating HbF compensates for this problem.

Why Fetal Hemoglobin Is So Protective

Fetal hemoglobin:

- is resistant to sickling,

- improves red-blood-cell flexibility,

- increases oxygen carrying capacity,

- reduces pain crises, hemolysis, and organ complications in sickle cell disease,

- and substitutes for the missing or defective β-globin in β-thalassemia.

This is why BCL11A targeting has become the central strategy in gene therapy for these blood disorders.

Limitations and Things Scientists Still Need to Study

The study highlights promising new directions, but also important considerations.

One limitation is that BCL11A plays roles in other tissues. Completely removing it everywhere would be harmful. Fortunately, enhancer-targeting therapies (both CRISPR and ASO-based) are designed to be erythroid-specific, meaning they mainly affect red-blood-cell precursors.

However:

- Long-term safety of ASO-based BCL11A suppression remains unknown.

- We do not yet know whether ASOs can maintain stable fetal hemoglobin induction over many years.

- Dose, delivery method, and off-target effects will all need thorough examination.

- It’s unclear how this approach would compare in durability to one-time CRISPR treatment.

Still, this research provides a strong scientific basis for exploring ASO-based therapies as a realistic alternative.

Why This Study Matters

This new understanding marks a meaningful step forward in several ways:

- It gives the clearest explanation yet for why CRISPR-based gene therapy works so effectively for these diseases.

- It identifies a new biological vulnerability — the enhancer RNA — that could be targeted without needing expensive genome editing.

- It opens up the possibility for more accessible, scalable, and affordable treatments that could reach patients worldwide, including regions most affected by sickle cell disease.

- It deepens scientific understanding of how enhancers, chromatin structures, and gene expression interact during blood cell development.

For people following advances in genetic medicine, this study is a reminder of how fast the field is moving — from editing DNA, to manipulating 3D chromatin structure, to targeting non-coding regulatory RNA.

Extra Background: What Are Enhancers and Why Are They So Powerful?

To give readers additional context, here’s a simple explanation of the molecular players involved.

What Is an Enhancer?

An enhancer is a DNA sequence that boosts the expression of a gene, often from far away. Enhancers don’t encode proteins. Instead, they act like switches that strengthen the activity of other genes.

What Is a Chromatin Structure Like a Rosette?

DNA is not linear inside cells. It folds into 3D shapes that can bring distant genetic elements into contact. A chromatin “rosette” is a looping configuration where several DNA segments cluster closely together to coordinate regulation.

What Are Enhancer RNAs?

Enhancer RNAs are short-lived RNA molecules transcribed from enhancer regions. They help maintain enhancer activity and sometimes stabilize 3D genome architecture.

Why Do These Matter for Therapy?

Targeting enhancers or enhancer RNAs can regulate gene expression without turning genes off everywhere in the body — allowing cell-type-specific control. This is crucial when a gene like BCL11A has roles beyond red cells.

Research Paper:

Silencing of BCL11A by Disrupting Enhancer-Dependent Epigenetic Insulation (Blood, 2025)

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2025030211