New Study Finds That “Normal” Vitamin B12 Levels May Not Be Enough to Protect the Brain

A new study from researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) has raised serious questions about what we consider “normal” levels of vitamin B12, especially when it comes to protecting the brain in older adults. The findings, published in the Annals of Neurology in February 2025, suggest that even people whose blood tests fall well within the normal range may still face risks of slower brain processing, white matter damage, and cognitive decline if their B12 levels are at the lower end of that spectrum.

This discovery has led to growing calls for a reevaluation of current vitamin B12 guidelines. Let’s break down exactly what the scientists found, what it means, and why it could change how we approach nutrition and brain health.

What the Study Looked At

The UCSF research team examined 231 healthy older adults, with an average age of about 71 years, none of whom had dementia or mild cognitive impairment. These participants were enrolled through the Brain Aging Network for Cognitive Health (BrANCH) study.

The researchers measured both total vitamin B12 in the blood and a more precise form called holo-transcobalamin (holo-TC), often referred to as “active B12.” This distinction matters because total B12 includes both active and inactive forms, but only active B12 is available for the body and brain to use.

Key tests in the study included:

- Cognitive testing, particularly focused on processing speed and visual response times.

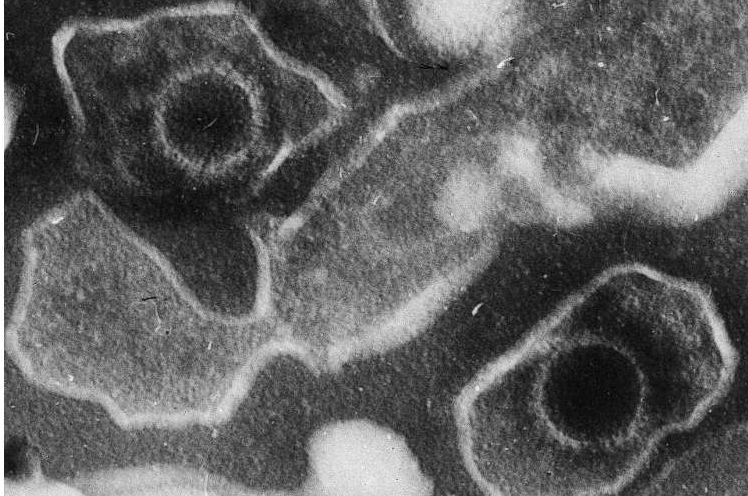

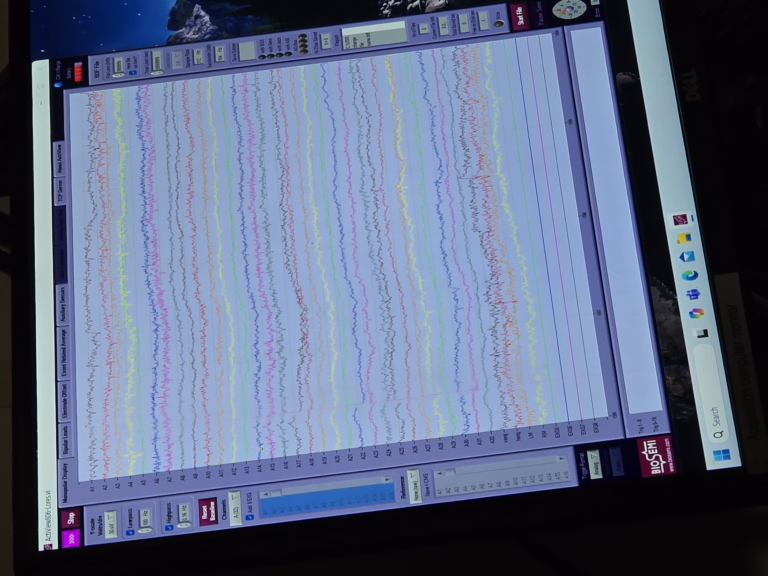

- MRI brain scans, to look for lesions and damage in the brain’s white matter (the tissue that connects different brain regions).

- Multifocal visual evoked potentials (mfVEPs), which measure how quickly nerve signals travel along the visual pathways, providing insight into myelin health.

- Blood biomarkers, including tau protein, UCH-L1, and other substances that can signal neurodegeneration.

What the Researchers Found

The results were clear: even within the “normal” range, lower B12 levels were linked to poorer brain outcomes.

- Processing Speed: Participants with lower active B12 scored lower on tests measuring processing speed. This effect became more pronounced with age, suggesting that older adults are especially vulnerable to low-normal B12.

- Brain Connectivity: Those with lower B12 showed slower responses to visual stimuli, pointing to delays in brain signal conduction.

- White Matter Lesions: MRI scans revealed that participants with lower active B12 had more white matter damage. White matter lesions are often linked to conditions such as dementia and stroke.

- Neurodegeneration Markers: Interestingly, participants with higher levels of inactive B12 showed elevated markers of neurodegeneration such as tau protein and UCH-L1, hinting that simply having “enough” total B12 in the blood may not tell the whole story.

Why This Matters

The current U.S. guidelines consider a B12 level above 148 pmol/L sufficient. However, the participants in this study had an average level of 414.8 pmol/L, far above the official cutoff. Yet, the ones with lower active B12 within this range still showed cognitive and neurological weaknesses.

This suggests that current definitions of deficiency may be outdated. In fact, the researchers argue that instead of just looking at total B12, doctors should pay more attention to functional biomarkers, like holo-TC, which give a better picture of what the body can actually use.

Rethinking Vitamin B12 Guidelines

The study’s authors, including neurologist Dr. Ari J. Green of UCSF, emphasize that the thresholds we use today were largely based on avoiding overt symptoms like anemia. But subtle brain-related effects may appear much earlier and go unnoticed until significant damage occurs.

This could mean that older adults with perfectly “normal” blood tests are still at risk of preventable cognitive decline. Clinicians may need to consider supplementation or further testing for older patients with neurological symptoms even if their B12 levels look fine on paper.

How Vitamin B12 Works in the Body

To fully appreciate these findings, it helps to understand why B12 is so important.

- DNA and Red Blood Cells: Vitamin B12 is essential for making DNA and healthy red blood cells.

- Nerve Tissue and Myelin: B12 plays a crucial role in building and maintaining myelin, the protective sheath around nerves that allows signals to travel quickly and efficiently.

- Brain Function: Because of its role in nerve signaling, B12 deficiency is well known to cause memory issues, mood changes, and in severe cases, permanent neurological damage.

Sources of Vitamin B12

One challenge with B12 is that the human body cannot produce it on its own. It must come from external sources:

- Animal products: Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy are the richest sources.

- Fortified foods: Many cereals, plant-based milks, and nutritional yeast products are fortified with B12.

- Supplements: B12 supplements are widely available and often recommended for people with absorption issues or restrictive diets.

For vegetarians and vegans, B12 supplementation or fortified foods are usually necessary to maintain adequate levels.

Why Older Adults Are More at Risk

As people age, they are more likely to have trouble absorbing B12 from food. This can happen due to reduced stomach acid, certain medications (like proton pump inhibitors and metformin), or medical conditions affecting the gut.

Because of this, organizations like the National Institutes of Health recommend that adults over 50 get their B12 primarily from supplements or fortified foods, rather than relying solely on natural dietary sources.

What This Study Adds to Existing Knowledge

There have been previous trials, such as the VITACOG study, which showed that supplementing with B vitamins, including B12, could slow brain atrophy in older adults with mild cognitive impairment.

The new UCSF study builds on this by showing that problems can begin even earlier—before clinical deficiency—and that active B12 levels might be a better predictor of brain health than total B12.

It also introduces the intriguing idea that high inactive B12 could be linked to elevated brain degeneration markers. While more research is needed, this raises questions about whether simply having a “high” total B12 level is necessarily protective.

What This Could Mean for the Future

The implications of this research are significant:

- Guideline changes: Medical organizations may need to reconsider what counts as “enough” B12.

- Routine testing updates: Doctors might begin ordering holo-TC tests more frequently, especially for older patients with cognitive complaints.

- Preventive care: Supplementation could become more common even for people who technically fall within the “normal” range, to reduce risks of brain decline.

Limitations of the Study

It’s worth noting a few caveats:

- The study was observational, meaning it can’t prove causation—only strong associations.

- It focused on healthy older adults, so the results may not apply to younger populations.

- While the study uncovered links between inactive B12 and neurodegeneration markers, the underlying biology isn’t yet fully understood.

Still, the consistency of the findings across multiple measures (cognitive tests, brain scans, and biomarkers) makes the evidence hard to ignore.

Practical Takeaways

For now, here’s what this research suggests for everyday life:

- Don’t ignore subtle symptoms. Tingling, balance problems, and even mild cognitive slowing should be taken seriously, even if blood tests are “normal.”

- Ask about active B12. If you’re older and concerned about brain health, talk to your doctor about checking holo-TC or secondary markers like methylmalonic acid (MMA) and homocysteine.

- Consider diet and supplementation. Meeting the basic dietary requirement may not always be enough for the brain, particularly in older age.

The Bigger Picture

Vitamin B12 has long been associated with anemia and obvious neurological problems when deficient. What this new research shows is that the story is much more nuanced. The brain may require higher thresholds of active B12 than previously thought, and older adults may be quietly vulnerable long before clinical deficiency shows up on a blood test.

This finding adds to a growing body of evidence that nutrition plays a much larger role in preserving cognitive health than guidelines currently reflect. If future studies confirm these results, we may see a significant shift in how doctors screen and treat patients for B12 insufficiency.

Research Reference:

Vitamin B12 Levels Association with Functional and Structural Biomarkers of Central Nervous System Injury in Older Adults – Annals of Neurology (February 2025)