New Study Reveals How the Nerve-Repair Protein SARM1 Plays a Dual and Unexpected Role in Both Damage and Healing

A new mouse study from the University of Michigan has shed light on the surprisingly complex job of SARM1, a protein long known as a key driver of nerve degeneration. For years, researchers believed that blocking SARM1 would be universally helpful—especially for conditions involving nerve damage such as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, diabetes-related nerve injury, or traumatic accidents. But this new research suggests that SARM1 is doing more than just breaking things down. It also helps set the stage for nerves to repair themselves, meaning the protein may be essential for both degeneration and regeneration.

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, examined how nerves behave when mice are genetically engineered to lack SARM1. Under normal conditions, SARM1 triggers a rapid degeneration process after injury, clearing out the damaged portion of the nerve. Scientists had previously assumed that stopping this breakdown would be beneficial because less nerve destruction should mean less long-term impairment. But when the University of Michigan team looked closely at what happens without SARM1, the picture was far more complicated.

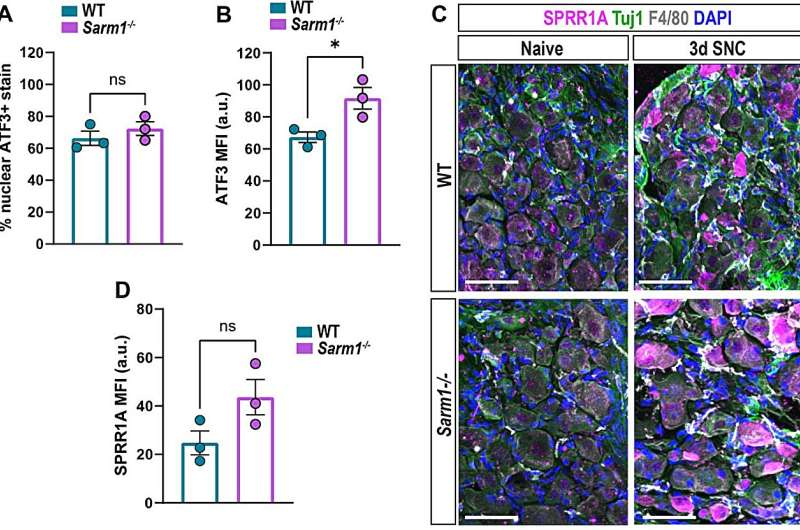

To explore this, researchers bred mice with Sarm1 completely deleted, then performed a controlled peripheral nerve injury. When they examined what happened afterward, they observed dramatic and unexpected shifts in the nerve’s internal environment. Normally, after a nerve is damaged, the distal portion of the axon—meaning the part furthest from the cell body—breaks down quickly. This degeneration attracts immune cells that rush in to remove debris, while specialized glial cells called Schwann cells transform into a repair-promoting state that supports axon regrowth. Without SARM1, however, this entire system was disrupted.

One of the most striking findings was the reduction of blood-borne immune cells entering the injured nerve. These immune cells play a crucial role in cleaning up broken axon fragments and myelin. With fewer of them available, debris clearance became slower and less efficient. The injured area also showed reduced inflammation, but not in a helpful way—rather, the process seemed incomplete, leaving the environment poorly prepared for new growth.

This led directly to problems with Schwann cells, which normally respond to injury by shifting into a regenerative mode. When the researchers examined nerves from mice lacking SARM1, they found that the Schwann cells remained essentially stuck in their original state. They did not switch into the repair phenotype needed for proper regeneration. Even though the nerves attempted to regrow, they were doing so without the essential cellular support system that guides, stabilizes, and nourishes new axons.

Interestingly, the mice without SARM1 still initiated axon regrowth, and in some ways they even attempted to regrow vigorously. But because the supporting Schwann cells were not activated, the regeneration was much less efficient. The axons that did grow ended up being smaller in diameter, and some showed abnormal target innervation, meaning the nerve fibers may have reconnected to the wrong places or failed to reconnect where they should have. Functional recovery was delayed, and the overall quality of regeneration was noticeably compromised.

This dual behavior of SARM1—destructive but also necessary—forces a reconsideration of what “good” nerve healing looks like. For years, researchers believed that simply preventing degeneration would lead to better outcomes. It intuitively made sense: less destruction should mean more preservation. But this new study reveals that the early breakdown phase is not a purely harmful event. Instead, it sends extremely important signals that activate both immune cells and Schwann cells. Without those signals, the healing machinery does not start properly.

This has major implications for therapy development. Pharmaceutical companies have been exploring SARM1 inhibitors as treatments for neurological damage. If blocking SARM1 prevents degeneration but simultaneously prevents proper regeneration, then therapies will need to be designed with much greater nuance. The goal may not be to completely shut down SARM1, but to modulate it—perhaps delaying activation, adjusting timing, or combining SARM1-blocking drugs with treatments that artificially stimulate Schwann cells or immune responses. The new study highlights the importance of maintaining a balance between protecting nerves from early damage and ensuring they receive the cues needed for effective repair.

Although this work was done in mice, the researchers emphasized that further study in additional animal models is necessary. They also note the importance of examining how other proteins involved in nerve repair interact with SARM1. If this mechanism holds true across species, it could reshape how scientists think about peripheral nerve healing in humans. Because the peripheral nervous system does retain the ability to regenerate—albeit slowly—better understanding how proteins like SARM1 coordinate the cleanup-and-regrow cycle could open the door to future regenerative therapies.

What SARM1 Normally Does in Nerves

To understand why these findings matter, it helps to look at what SARM1 typically does. Under normal circumstances, SARM1 is the molecular trigger for axon self-destruction, a process known as Wallerian degeneration. This is a tightly controlled mechanism where the damaged part of a nerve deliberately breaks down so the body can clear it away. While it looks destructive, it is actually part of a biological program that prepares the way for new axon growth.

SARM1 activation leads to rapid breakdown of essential molecules within the axon, causing it to disintegrate. This event is followed by the arrival of immune cells that remove debris, and the transformation of Schwann cells into a regeneration-supporting state. The new study shows that without SARM1, this entire coordinated sequence fails to launch properly. Instead of a clean, well-regulated demolition followed by reconstruction, the injury site becomes a place where debris lingers and the support cells never receive the signal to jump into action.

Why Schwann Cells Matter in Nerve Repair

Schwann cells are essential players in peripheral nerve regeneration. They typically surround and insulate axons, but after injury, they undergo a dramatic conversion into repair Schwann cells. In this state, they change their gene expression patterns, reshape themselves to form pathways for axon growth, and produce factors that stimulate regrowth. Without Schwann cells making this switch, regeneration becomes slow, disorganized, and incomplete.

The study’s finding that Schwann cells remain inert without SARM1 is one of the strongest indicators that degeneration and regeneration are not separate processes, but directly linked stages of one complex recovery pathway.

The Bigger Picture for Future Research

While the idea of stopping nerve degeneration remains appealing, this study emphasizes that protecting nerves from breaking down is only part of the solution. Any effective therapy must account for the whole environment around the injured nerve—including immune signaling, debris clearance, and Schwann cell activation. It also raises questions about how SARM1 inhibitors should be timed or combined with other therapies.

As the field moves forward, scientists will likely explore ways to fine-tune SARM1 activity rather than eliminate it completely. If the balance between preservation and regeneration can be controlled, it may lead to future treatments capable of improving nerve recovery in patients with chronic neuropathy, traumatic injuries, or neurological side effects from chemotherapy.

Research Paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.adp9155