One Way Brain “Conductors” Find Their Precise Connection to Target Cells

New research has shed light on a long-standing question in neuroscience: how certain neurons in the brain form incredibly precise connections with the exact part of another neuron they are meant to control. These neurons, often described as the brain’s “conductors,” play a critical role in coordinating neural activity, and understanding how they wire themselves into brain circuits may help explain what goes wrong in several neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The study focuses on a special class of inhibitory neurons called chandelier cells. These cells do not connect randomly. Instead, they form synapses at a very specific location on their target neurons, allowing them to exert powerful control over brain activity. Researchers have now identified two key molecules that must be present for this highly targeted connection to form.

Why Chandelier Cells Matter

Chandelier cells are a type of inhibitory interneuron found in the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer responsible for functions such as perception, thought, and decision-making. Unlike excitatory neurons, which increase activity in brain circuits, inhibitory neurons limit and fine-tune activity, preventing the system from becoming overly excited.

What makes chandelier cells special is where they connect. They target a tiny but crucial region of excitatory neurons called the axon initial segment (AIS). This is the part of the neuron where electrical signals, known as action potentials, are generated. By forming synapses here, chandelier cells are positioned to exert exceptionally strong influence over whether excitatory neurons fire or remain silent.

Because of this unique placement, chandelier cells are often described as master regulators of neural circuits. Disruptions in their function have been linked to disorders such as epilepsy, schizophrenia, autism, and depression, all of which involve imbalances between excitation and inhibition in the brain.

The Challenge of Precise Neural Wiring

One of the biggest mysteries in neuroscience is how neurons manage to form highly specific connections in the crowded environment of the developing brain. A single neuron is surrounded by thousands of others, yet it somehow finds the correct partner and the exact subcellular location to connect with.

In this study, researchers set out to understand how chandelier cells recognize the axon initial segment of pyramidal neurons, the main excitatory cells of the cortex. Previous work suggested that cell adhesion molecules, proteins that help cells stick to one another, might be responsible for guiding this specificity.

Discovering the Molecular “Handshake”

Using RNA sequencing, the research team compared gene expression across different types of inhibitory interneurons. This approach allowed them to identify genes that were especially active in chandelier cells. One protein stood out: gliomedin.

Gliomedin is a cell-surface molecule that was already known for its role in nerve development outside the brain. Importantly, it is a known binding partner for another protein, neurofascin-186, which is located specifically at the axon initial segment of neurons.

This pairing suggested a potential molecular handshake: gliomedin on chandelier cells interacting with neurofascin-186 on pyramidal neurons to guide synapse formation at precisely the right spot.

Evidence from Developing Mouse Brains

To test this idea, researchers examined the brains of very young mice during a developmental period roughly comparable to human adolescence, when many neural circuits are still being refined.

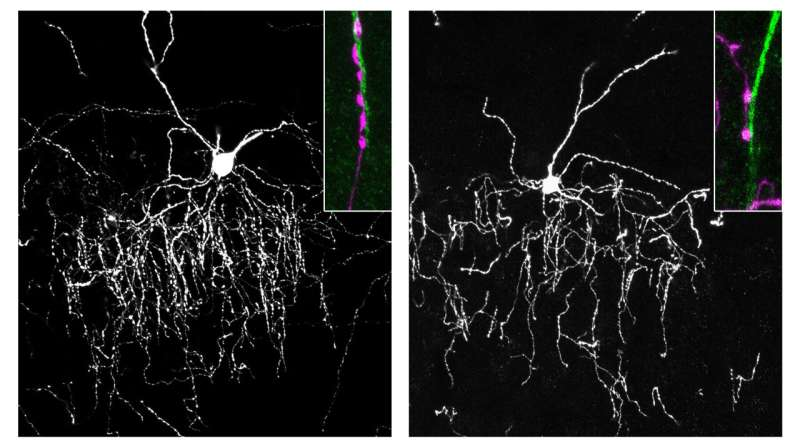

Using fluorescent dyes to label cells, they observed chandelier cells forming their characteristic synaptic cartridges along the axon initial segments of pyramidal neurons. Under normal conditions, these synapses were densely and precisely arranged.

However, when the genes responsible for producing gliomedin were deleted, the results changed dramatically. Fewer synapses formed on the axon initial segment, indicating that gliomedin is essential for proper connection. The same effect was seen when neurofascin-186 was disrupted on the pyramidal neurons.

On the other hand, when the genes for these proteins were overexpressed, synapse formation increased. This confirmed that both proteins are not only necessary but actively promote the formation of chandelier cell synapses at the axon initial segment.

Why the Axon Initial Segment Is So Important

The axon initial segment is often described as the neuron’s decision-making zone. This is where incoming signals are integrated and converted into action potentials that travel down the axon to communicate with other neurons.

By targeting this location, chandelier cells can effectively control the output of excitatory neurons. If they suppress activity at the axon initial segment, the neuron may fail to transmit signals entirely. This level of control explains why chandelier cells are considered among the most influential inhibitory neurons in the brain.

Implications for Brain Disorders

Although this research is considered basic neuroscience, its implications are far-reaching. Many brain disorders are associated with disrupted inhibitory control and faulty neural wiring. If the molecular handshake between gliomedin and neurofascin-186 is impaired, chandelier cells may fail to form proper connections, leading to circuit malfunction.

While the study does not directly link these molecular disruptions to specific diseases, it opens the door to future research exploring whether mutations or altered expression of these proteins play a role in conditions such as schizophrenia or epilepsy.

A Broader View of Interneuron Diversity

Chandelier cells are just one subtype of inhibitory interneurons. The brain contains many others, each with its own connection patterns and functions. The researchers suggest that similar molecular strategies may guide other interneurons to their specific targets, though the exact proteins involved may differ.

By applying the same investigative approach, scientists may eventually uncover a general set of rules that explain how the brain builds its incredibly precise and complex circuitry.

What This Research Adds to Neuroscience

This study provides a clear example of how molecular interactions at the cell surface can dictate synapse placement at a subcellular level. It shows that neurons do not need to “see” their targets in a visual sense; instead, they rely on chemical signals and protein interactions to find the correct connection points.

Beyond its technical insights, the work highlights the remarkable organization of the brain, where billions of neurons form trillions of synapses with astonishing precision.

Research Reference

The highly localized interaction between Neurofascin-186 and Gliomedin promotes subcellular innervation by the chandelier cell, Journal of Neuroscience (2025).

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/early/2025/11/17/JNEUROSCI.0464-25.2025