Psilocybin from Magic Mushrooms Shows Powerful, Lasting Relief for Pain and Depression, Penn Medicine Study Finds

A new study from Penn Medicine’s Perelman School of Medicine, published in Nature Neuroscience, has uncovered something remarkable about psilocybin—the active compound in so-called magic mushrooms. Scientists found that this psychedelic substance can ease chronic pain and depression by rebalancing brain circuits that link emotional and physical suffering. Even more interesting, a single dose of psilocybin produced relief lasting nearly two weeks in mice, showing promise for new non-opioid treatments for pain and mood disorders.

Understanding Psilocybin and Why It Matters

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain species of mushrooms. When ingested, it’s converted into psilocin, a substance that interacts with serotonin receptors in the brain. These receptors—particularly 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A—are key players in mood regulation, perception, and emotional processing.

Over the past decade, psilocybin has gained attention for its potential in treating treatment-resistant depression, anxiety, addiction, and even end-of-life distress. What makes this new research from Penn Medicine stand out is that it links psilocybin to pain relief—an area typically dominated by opioids, which are often addictive and carry serious side effects.

If psilocybin can truly break the vicious cycle of chronic pain and depression, it could transform how medicine approaches two of the most common and intertwined health challenges worldwide.

The Growing Problem of Chronic Pain

Chronic pain affects over 1.5 billion people globally, often leaving them stuck in a loop where physical pain worsens mood, and depression amplifies the perception of pain. Conventional treatments—ranging from prescription opioids to antidepressants—tend to target one side of this problem, not both.

As the opioid crisis continues to devastate communities, researchers have been urgently searching for safer, longer-lasting, and non-addictive alternatives. This new study suggests that psilocybin may be one of the most promising candidates yet.

How the Penn Medicine Study Was Done

The research team, led by Dr. Joseph Cichon, an assistant professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, and Neuroscience PhD student Stephen Wisser, designed a detailed series of experiments using mice to explore how psilocybin affects pain and mood.

They used two well-established models of chronic pain:

- Spared nerve injury (SNI) – representing nerve-related (neuropathic) pain.

- Complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) – modeling inflammatory pain.

After inducing pain, they gave mice a single dose of psilocybin and carefully tracked the effects over time. Behavioral tests measured both pain sensitivity and depression-like behaviors such as decreased exploration or lack of motivation.

Results: One Dose, Two Weeks of Relief

The outcome was striking. One dose of psilocybin significantly reduced pain sensitivity and reversed depression-like behaviors caused by chronic pain. Even more impressive, these effects lasted for almost two weeks—long after the immediate drug effects had worn off.

This duration suggests that psilocybin doesn’t simply mask pain; it changes the way the brain processes it.

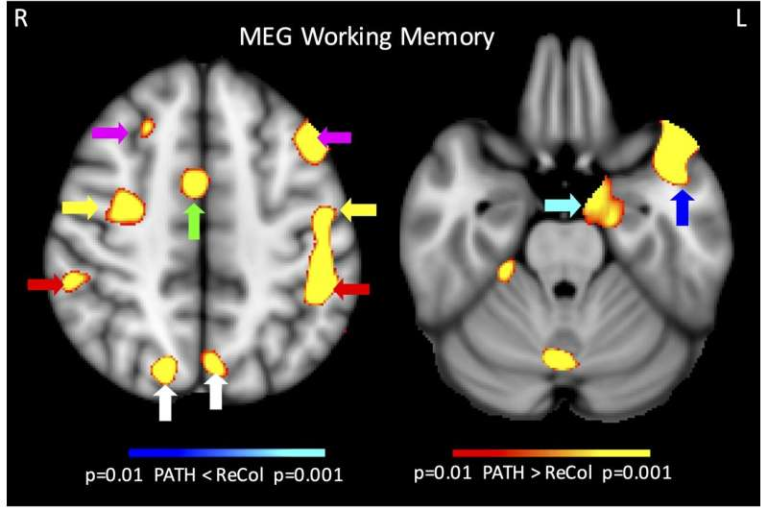

The Brain Circuit Behind It

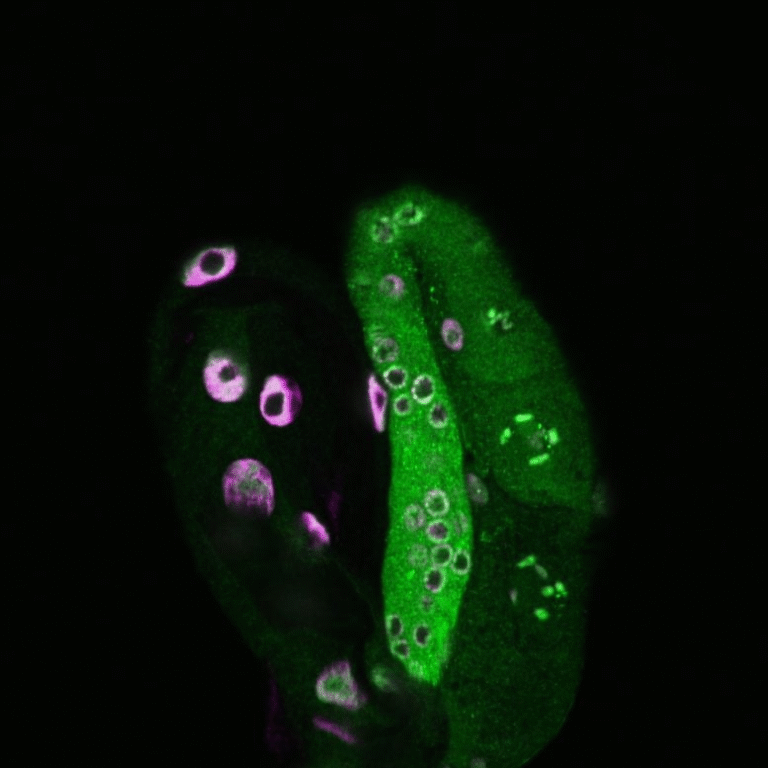

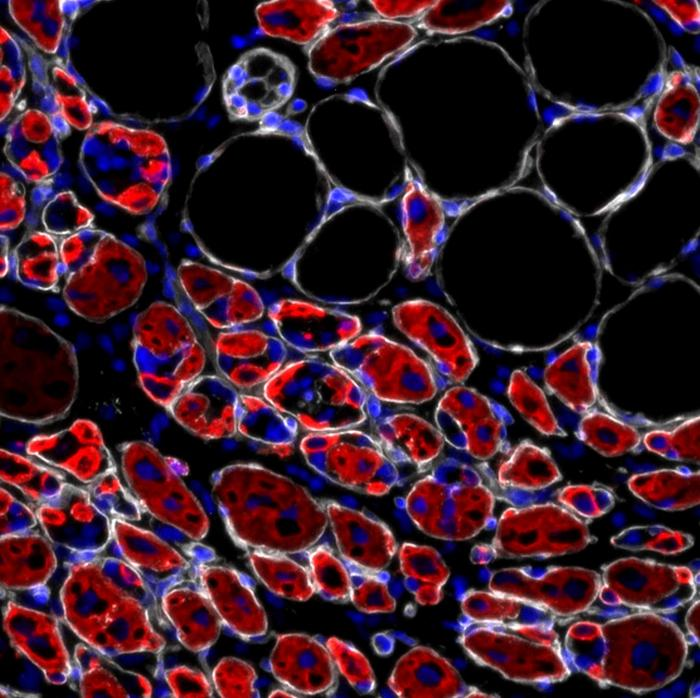

To understand where this change was happening, researchers looked closely at specific brain regions. Using advanced fluorescent microscopy (a technique that lights up active neurons), they tracked the effects of psilocin—the active form of psilocybin—on neuron activity.

The key region they identified was the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a part of the prefrontal cortex responsible for integrating pain and emotion. This region is often overactive in people and animals with chronic pain, which contributes to both the sensation of pain and the emotional distress that comes with it.

When psilocin was injected directly into the ACC, the mice showed the same improvements as when psilocybin was given systemically. However, when psilocin was injected into the spinal cord, it had no significant effect. This finding confirmed that psilocybin’s power lies in modulating brain circuits, not directly numbing the pain at its source.

In essence, psilocybin tunes the brain’s pain-emotion connection, bringing it back into balance.

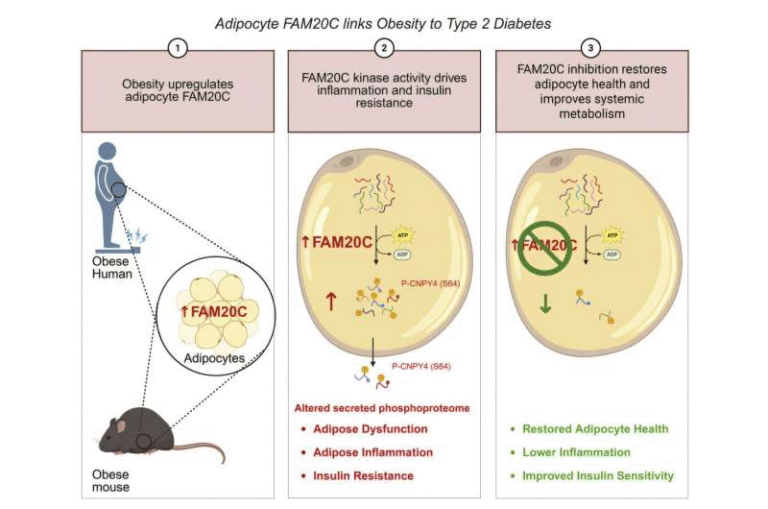

The Serotonin “Dimmer Switch” Effect

Unlike drugs that flood or shut down serotonin signaling, psilocybin works more subtly. It acts as a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors, meaning it doesn’t fully turn these systems on or off. Instead, it functions more like a dimmer switch, adjusting brain activity to a balanced state.

This fine-tuning seems to help calm overactive circuits responsible for amplifying pain signals while also lifting mood and motivation. The result is a rare dual benefit—less pain and less emotional suffering, achieved through a single mechanism.

Evidence from Neuron Imaging

The team’s imaging studies provided a visual confirmation of this effect. In mice suffering from chronic pain, neurons in the ACC showed hyperactivity, firing excessively and unpredictably. After psilocybin treatment, this overactivity normalized, and neuron firing became more stable.

That’s a major insight. It means psilocybin may not just offer symptom relief but actually restore healthier brain function. By resetting the overexcited circuits that link pain and emotion, it could provide longer-lasting benefits than standard painkillers or antidepressants.

Broader Implications and Future Research

The researchers believe this mechanism could have broader applications for conditions involving dysregulated brain circuits, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and addiction. Both conditions involve abnormal activity in the prefrontal cortex and ACC, just like chronic pain and depression.

However, the team emphasizes that this is early-stage research. The findings are based on rodent models, not humans. The next steps include:

- Determining optimal dosing strategies for sustained benefits.

- Understanding how long the brain’s rebalanced state lasts.

- Studying whether multiple doses or combinations with therapy could enhance effects.

- Investigating the safety and feasibility of psilocybin use around surgery and anesthesia, since these contexts involve both physical and emotional stress.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R35GM151160-01) and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) Chronic Pain Medicine Research Award.

Why This Matters: Beyond the Opioid Era

One of the most pressing needs in medicine today is finding non-addictive alternatives to opioids for chronic pain. Opioids can effectively reduce pain but often come at a devastating cost—dependence, tolerance, and overdose risk.

Psilocybin, on the other hand, does not cause physical dependence, and when used in controlled settings, appears to have a much safer profile. If future studies in humans confirm these results, psilocybin-based therapies could offer a way to manage both pain and depression without the risks associated with opioid use.

Moreover, psilocybin’s ability to affect both emotional and physical pain simultaneously makes it unique. Many chronic pain patients describe their suffering as more than just physical—it’s deeply emotional. A treatment that targets both aspects at once could finally provide comprehensive relief.

How This Fits Into the Larger Psychedelic Research Trend

This study is part of a growing scientific movement re-examining psychedelics as medical tools. Over the past few years, institutions like Johns Hopkins University, Imperial College London, and UCLA have conducted clinical trials showing that psilocybin can produce rapid and lasting improvements in depression and anxiety, sometimes after just one or two sessions.

These results challenge decades of stigma around psychedelics and suggest they may have legitimate medical value when used responsibly and under supervision.

Other studies are exploring psilocybin for:

- Cluster headaches and migraine relief

- Addiction treatment (especially nicotine and alcohol)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- End-of-life anxiety in terminally ill patients

The consistent pattern is that psilocybin helps reset the brain, promoting flexibility and emotional balance.

A Note of Caution

While the findings are promising, psilocybin is still a Schedule I controlled substance in many countries, including the United States. That means it’s considered to have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse—though this classification is increasingly being challenged by researchers and lawmakers.

Clinical trials are ongoing to test psilocybin’s safety and effectiveness in humans, and early results are encouraging. But before psilocybin can be prescribed as a treatment, more evidence is needed on long-term safety, dosing, and the right therapeutic context.

In other words, we’re still in the early chapters of understanding how this ancient compound could fit into modern medicine.

The Bigger Picture

The idea that a single natural compound can reshape the brain’s response to pain and emotion is both fascinating and hopeful. The Penn Medicine study provides a biological explanation for why psilocybin might work so well—by re-balancing overactive brain circuits instead of just numbing the symptoms.

If these effects translate to humans, psilocybin could open the door to a new class of treatments that are non-addictive, long-lasting, and holistic, addressing both the physical and emotional components of suffering.

The research team plans to continue exploring how psilocybin changes neural pathways over time, how many doses might be optimal, and how durable the brain’s re-wiring remains. For now, their findings add powerful scientific weight to the growing idea that psychedelics might one day play a real role in pain medicine.