Researchers Are Getting Closer to Safer Opioid Painkillers Without Deadly Side Effects

Researchers at USF Health are making important progress toward one of medicine’s most difficult goals: creating opioid painkillers that still relieve pain but are far less dangerous. In newly published studies, scientists have uncovered a previously underappreciated way opioid receptors work inside the body, opening the door to designing drugs that may reduce pain without triggering severe side effects like respiratory suppression and rapid tolerance.

The findings come from two closely related research papers published in Nature and Nature Communications in 2025. Together, they offer a deeper understanding of how opioid receptors behave at the molecular level and how future drugs could take advantage of this behavior to be safer and more effective.

How Opioid Pain Relief Usually Works — and Why It’s Dangerous

Most commonly used opioid drugs, including morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl, relieve pain by binding to the mu opioid receptor. This receptor is a specialized protein found on nerve cells that plays a major role in blocking pain signals traveling through the nervous system.

While this mechanism is very effective for pain relief, it also activates other biological pathways that cause serious side effects. These include respiratory depression, which slows or stops breathing, as well as sedation, tolerance, and physical dependence. Over time, patients often need higher doses to achieve the same pain relief, dramatically increasing the risk of overdose.

The challenge for scientists has been clear for decades: how can opioids keep their painkilling power while shedding their most dangerous effects?

A New Way of Looking at Opioid Receptors

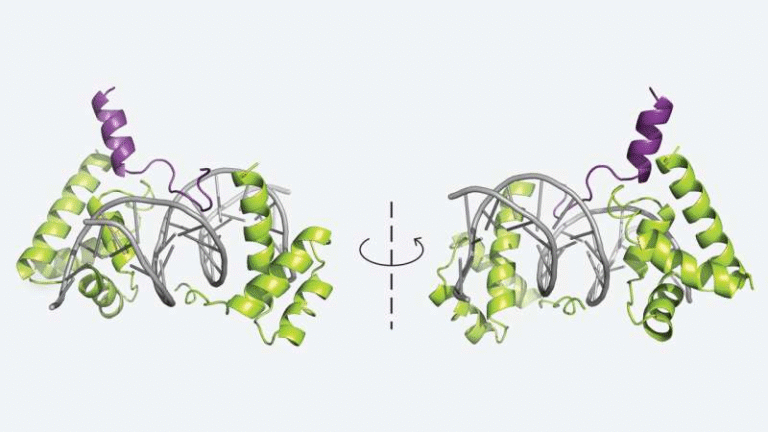

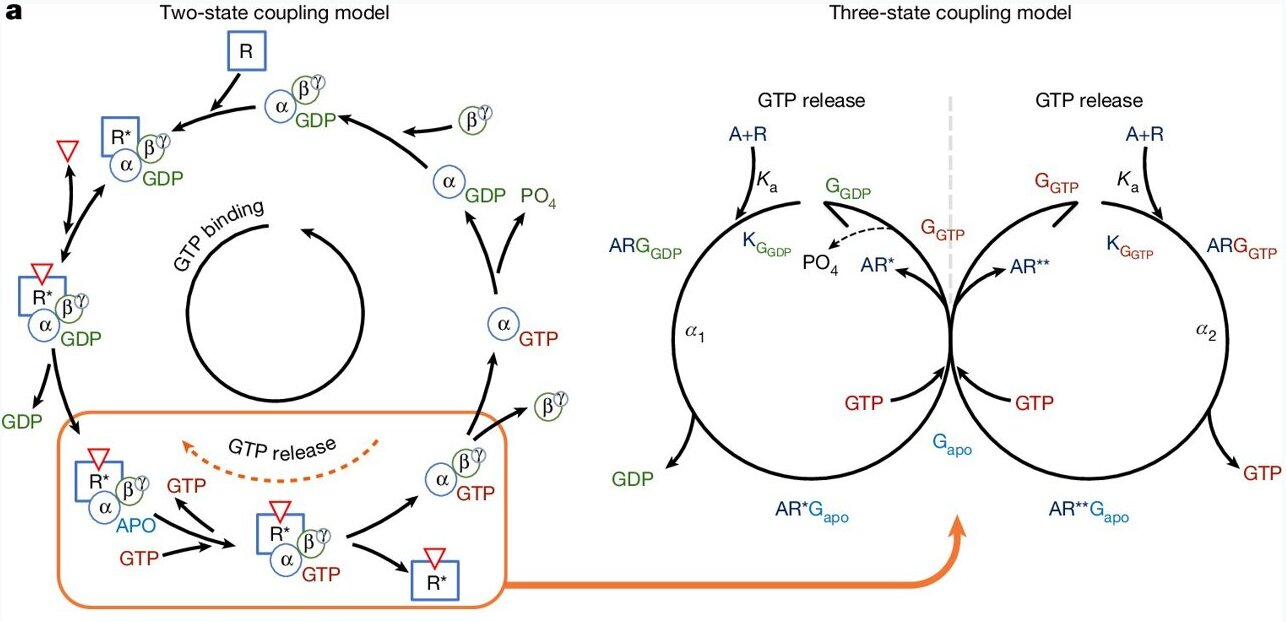

The USF Health research team, led by Laura M. Bohn, focused on how opioid receptors interact with G proteins, which act like molecular switches inside cells. Traditionally, scientists believed that when an opioid binds to its receptor, it triggers a single main process: the exchange of GDP for GTP, which turns on downstream signaling and produces pain relief along with side effects.

What this new research reveals is that the process is more flexible than previously thought.

The team discovered that opioid receptors can also favor a reverse reaction, one in which GTP is released instead of bound. This alternate signaling pathway changes how long and how strongly the receptor stays active.

Some experimental opioid compounds were found to strongly favor this reverse, GTP-release cycle. When tested in animal models, these compounds altered how pain relief unfolds over time.

Prolonging Pain Relief Without Worsening Breathing Problems

One of the most striking findings from the study is that two newly studied prototype molecules were able to enhance the pain-relieving effects of morphine and fentanyl without increasing respiratory suppression, at least at lower doses.

When administered at doses that were not effective on their own, these compounds prolonged opioid analgesia, meaning pain relief lasted longer than usual. Importantly, they did not amplify breathing suppression, which is the primary cause of fatal opioid overdoses.

This suggests that certain drugs can fine-tune opioid receptor behavior rather than simply turning it on or off. By nudging the receptor toward the reverse signaling direction, researchers may be able to decouple pain relief from dangerous side effects.

However, the researchers are careful to emphasize that these compounds are not ready for clinical use. At higher doses, they still suppress respiration, and they have not been tested for toxicity or long-term safety. For now, they serve as proof-of-concept molecules, helping scientists understand what is possible.

Why This Matters for Opioid Tolerance

Another major issue with opioids is tolerance development. Over time, repeated opioid use causes the receptors to respond less effectively, forcing patients to increase their dosage.

The new findings suggest that manipulating the earliest step of receptor signaling could help slow or alter tolerance formation. If receptors are activated differently at the molecular level, they may not shut down or adapt as quickly.

This is especially important for people with chronic pain, who may rely on opioids for long periods and face growing risks as tolerance builds.

Building on Earlier Breakthroughs Like SR-17018

Dr. Bohn’s lab is not new to this field. Several years ago, the team discovered a compound called SR-17018, which also activates the mu opioid receptor but in a unique way. Unlike traditional opioids, SR-17018 does not cause respiratory suppression or tolerance in preclinical studies.

One key difference is that SR-17018 leaves the receptor more available to the body’s own natural pain-relieving chemicals, rather than locking it into a tightly closed state.

The new research provides additional tools to improve upon SR-17018, potentially combining its favorable properties with the newly discovered reverse signaling mechanism. This could guide the design of future opioids that are both long-lasting and safer.

Beyond Opioids: Implications for Other Receptors

Although the studies focus on opioid receptors, the implications go much further. The researchers point out that other receptors, including the serotonin 1A receptor, also appear capable of signaling in a reverse direction.

This receptor is an important drug target for depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Understanding how reverse signaling works could influence drug development well beyond pain management, offering new ways to design treatments for a wide range of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Why This Research Matters in the Bigger Picture

The timing of this research is especially significant given the ongoing opioid overdose crisis. Data from 2024 show that 68% of all overdose deaths involved opioids, and 88% of those were linked to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

While non-opioid pain treatments are advancing, opioids remain essential for many medical situations, including severe trauma, cancer pain, and post-surgical recovery. The goal is not necessarily to eliminate opioids altogether, but to make them safer and more predictable.

By expanding our understanding of how receptors work at the most fundamental level, this research adds an important new chapter to pharmacology textbooks and drug development strategies.

What Comes Next

The researchers emphasize that these discoveries are foundational rather than final. Turning these insights into real medications will require years of additional testing, optimization, and clinical trials.

Still, the work provides a clear roadmap. By targeting how receptors cycle through signaling states, rather than simply binding more tightly or loosely, scientists may finally be able to design opioids that offer effective pain relief with far fewer risks.

Research References

GTP release-selective agonists prolong opioid analgesic efficacy – Nature (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09880-5

Characterization of the GTPγS release function of a G protein-coupled receptor – Nature Communications (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66516-y