Researchers Develop a New Way to Measure Emotional Intensity Using Skin Conductance Responses to Sound, Images, and Touch

A team of researchers from NYU Tandon School of Engineering and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai has introduced a detailed method to quantify how strongly people react to different sensory experiences—specifically sound, images, and touch—by analyzing subtle changes in skin conductance. Their work, published in PLOS Mental Health (2025), digs into how the body’s electrical responses can reveal cognitive arousal, which refers to a person’s level of mental alertness and emotional activation.

This study stands out because it combines physiological modeling, Bayesian filtering, and statistical algorithms to interpret variations in skin conductance more precisely than traditional approaches. Instead of relying on subjective self-reports alone, the researchers set out to understand what the body’s hidden signals can reveal.

Understanding What the Researchers Did

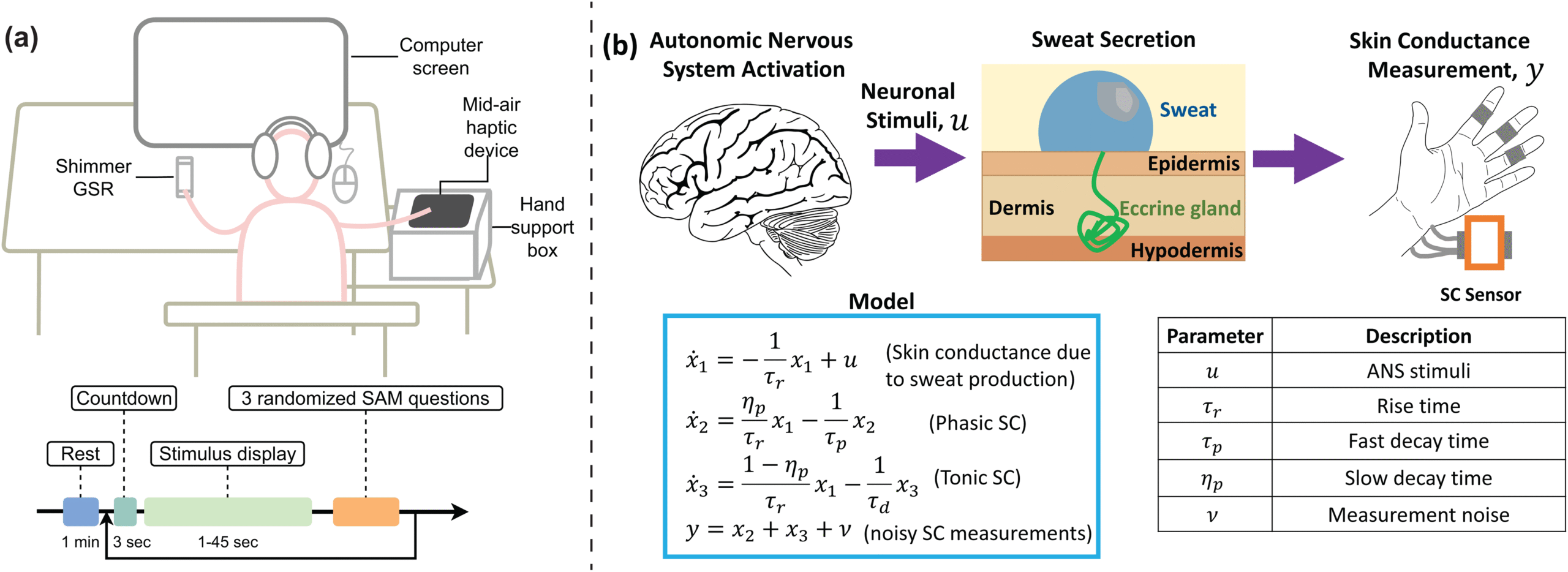

To explore how people respond emotionally to sensory experiences, the researchers analyzed a published dataset where participants were exposed to visual, auditory, and haptic (touch) stimuli. While participants viewed images, listened to sounds, or experienced gentle vibrations, their skin conductance (SC) was recorded continuously.

Participants also provided self-reported ratings of arousal using the Self-Assessment Manikin, a visual scale widely used in psychology to measure emotional states.

Skin conductance is a sensitive measure of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. When sweat glands are even slightly stimulated, the skin’s ability to conduct electricity changes. This is known as electrodermal activity, and for decades researchers have used it as an indicator of emotional and cognitive responses. What this study adds is a new way of modeling and interpreting those signals.

How the New Modeling Approach Works

Instead of treating skin conductance as one single curve that rises and falls, the team separated its slow and fast components using a physiologically informed state-space model. The fast components reflect immediate, rapid responses to stimuli, while the slow components reflect underlying baseline trends.

They modeled the ANS activity—essentially the neural pulsatile signals that trigger sweat gland responses—as the hidden input. The skin conductance values served as the measurable output. Using an expectation-maximization algorithm, the team estimated both the sweat secretion parameters and the hidden ANS activity.

To interpret how this internal activity translated into cognitive arousal, the researchers then applied Bayesian filtering and a marked point process algorithm that generated a continuous estimate of arousal over time.

This is important because most skin-conductance research focuses on discrete peaks. A continuous model offers a far more detailed picture of how emotional and cognitive responses unfold moment-by-moment.

What the Study Found

The analysis uncovered several interesting patterns:

- The autonomic nervous system reacted most strongly within two seconds of a new stimulus being presented.

- Among the three sensory categories, haptic (touch) stimuli produced the largest immediate physiological responses.

- However, when researchers compared physiological signals to participants’ own arousal ratings, auditory stimuli—especially music and various sounds—were more frequently associated with high self-reported arousal.

- After processing the physiological data into a modeled arousal estimate, the computed arousal aligned more closely with participants’ subjective impressions, particularly reinforcing that auditory stimuli generated the highest arousal levels for most participants.

- The model was able to track transitions between low and high arousal more accurately than chance.

- When separating participants into groups—those more reactive to visual stimuli versus those more reactive to touch—the model captured these group differences effectively.

All of this suggests that while raw body responses and conscious perceptions do not always perfectly align, advanced modeling can bring the two much closer together.

Why These Findings Matter

This research has several potentially valuable applications.

Better Mental Health Monitoring

Many treatments for conditions such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD rely on self-reporting. But self-reports can be incomplete or biased. Objective physiological measures of arousal could:

- supplement clinical assessments

- provide real-time measurements

- track subtle changes that patients may not notice

These continuous models could eventually support more personalized and responsive mental-health treatment plans.

Advancements in Human-Computer Interaction

In areas like virtual reality, gaming, and immersive experiences, understanding users’ emotional responses can dramatically improve design. Systems could adapt dynamically based on the user’s emotional state, for example:

- intensifying immersion

- reducing stress

- modifying sensory input

- adjusting content pacing

Such closed-loop systems would essentially allow machines to react to human emotion in real time.

Improved Research Tools

This model allows researchers to evaluate emotional and cognitive engagement with higher precision. It could help future studies investigate how people respond to:

- educational content

- advertisements

- environmental changes

- social interactions

- therapeutic stimuli

A Closer Look at Skin Conductance and Emotional Arousal

Skin conductance is governed by the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system—the same system responsible for fight-or-flight responses. When the brain perceives something as important, interesting, or emotionally charged, it often triggers tiny bursts of sweat gland activation.

Researchers have used skin conductance for decades because:

- it responds quickly

- it indicates physiological arousal

- it does not require conscious reporting

- it can be recorded continuously

However, older methods often focused only on identifying peaks, which oversimplifies the signal. The new approach takes advantage of more advanced models to capture nuanced patterns.

Challenges and Nuances in Measuring Arousal

Despite its promise, the study acknowledges several complexities:

- The correlation between skin-based arousal estimates and self-reported arousal was modest overall.

- Emotional arousal is personal and influenced by factors like prior experience, cultural background, and mood.

- Stimulus duration and intensity can vary, affecting responses differently.

- Individual differences in baseline skin conductance complicate comparisons.

Still, the consistency of the model in identifying moments of heightened engagement shows that physiological data, when processed intelligently, can reveal meaningful patterns.

Who Contributed to the Research

This project began as a course assignment in Rose Faghih’s Neural and Physiological Signal Processing class at NYU Tandon. Student authors Suzanne Oliver and Jinhan Zhang initiated the work, mentored by research scientist Vidya Raju.

Professor James W. Murrough, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist who directs the Depression and Anxiety Center for Discovery and Treatment at Mount Sinai, was also a collaborator.

The combination of engineering, neuroscience, and psychiatry highlights the interdisciplinary nature of this study.

What This Means for the Future

The research strengthens the idea that emotion and cognition can be tracked through physiological signals, especially when modeled in sophisticated ways. As technology continues to integrate deeper with daily life—through wearables, VR systems, and digital health tools—methods like these could help create emotion-aware technologies that adapt to users in meaningful ways.

At the same time, this work reinforces that human emotion is complex. Arousal measured through the body does not always mirror how we think we feel. Bridging that gap is an ongoing challenge—but this study represents a significant step forward.

Research Reference:

Cognitive arousal-based measures quantify insights from self-ratings in response to sensory stimuli — PLOS Mental Health (2025)